-

Ny Film Festival '06

Fiimleaf's coverage of the 44th New York Film Festival

INDEX OF LINKS TO REVIEWS:

40 Years of Janus Films: a NYFF Sidebar

49 Up (Michael Apted 2006)

August Days (Marc Recha 2006)

Bamako (Abderahmane Sissako 2006)

Belle Toujours (Manoel de Oliveira 2006)

Climates (Nuri Bilge Ceylan 2006)

Falling (Barbara Albert 2006)

Gardens in Autumn (Otar Iosseliani 2006)

Go Master, The (Tian Zhuangzhuang 2006)

Host, The (Bong Joon-ho 2006)

Inland Empire (David Lynch 2006)

Insiang (Lino Brocka 1976)

Journals of Knud Rasmussen (Zacharias Kunuk, Norman Cohn 2006)

Little Children (Todd Field 2006)

Mafioso (Alberto Latuado 1962)

Marie Antoinette (Sofia Coppola 2006)

Offside (Jaafar Panahi 2006)

Our Daily Bread (Nikolaus Geyrhalter 2006)

Pan's Labyrinth (Guillermo del Toro 2006)

Paprika (Satoshi Kon 2006)

Poison Friends (Emmanuel Bourdieu 2006)

Private Fears in Public Places (Alain Resnais 2006)

Queen, The (Stephen Frears 2006)

Reds (Warren Beatty 1981)

Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul 2006)

These Girls (Tahani Rached 2006)

Triad Election (Johnnie To 2006)

Volver (Pedro Almodóvar 2006)

Woman on the Beach (Hong Sang-soo 2006)

* * * * * *

NYFF 2006L: SOME RECOMMENDATIONS

NYFF 2006: An introduction

Helen Mirren in NYFF 2006 opener, Frears' The Queen

Press screenings of the 44th New York Film Festival presented by the Film Society of Lincoln Center begin September 18, 2006 and continue through October 12th. I'll be watching the press screenings and reviewing the films in the order they appear there. The festival public screenings will run from September 29 through October 15.

For the nature of the unique festival and my coverage of the films, see last year’s introdction and individual links on the site. Nothing has changed in the essential game plan except that this year there are twenty-eight official selections instead of twenty-five. Again the aim is to represent the very best and only the very best of the year in cinema internationally.No jury or prizes, no theme or categories. If I am not mistaken the selection committee, headed by Film Society program director Richard Peña, is the same as last year's. There are slightly more films in English than in other languages, but there’s a panoply of international directors represented including, among others:

Sofia Coppola

Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Alain Resnais

Pedro Almodóvar

Manoel de Oliveira

Michael Apted

Tian Zhuangzhuang

Stephen Frears

Guillermo del Toro

Todd Field

Hong Sang-soo

David Lynch

Jafar Panahi

There is also Japanese animé and a very few documentaries. Frears’ The Queen, a fictional depiction of the aftermath of the death of Lady Di in the British royal family, with Helen Mirren as Elizabeth II, is the opening night film. There are also three retrospective showings of older films, Lino Brocka’s Insiang (Filipino, 1976), Alberto Lattuada’s Mafioso (Italian, 1962), and the twenty-fifth anniversary screening of Warren Beatty’s Reds. Peña says he thinks as usual there will be “something for just about everybody.” A number of films deal with the topic of “popular cinema” using traditional genres such as melodrama or the gangster flick, and a unifying theme that has emerged in some of the selections is stories that “depict characters who are finally forced to confront realities they’ve long ignored or avoided.”

The standard set by last year's NYFF is a hard one to live up to, but since the same people are running the show, there's hope for another round of exceptional films.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:37 AM.

-

Sofia Coppola: Marie Antoinette (2006)

SOFIA COPPOLA: MARIE ANTOINETTE (2006)

Kirsten Dunst in Marie Antoinette

Such sad bonbons

Audacious, delicious, exaggerated and preposterous, Sofie Coppola’s third film, Marie Antoinette, plunges into the life of the Austrian princess who became queen of France and was beheaded in the Revolution, following Antonia Fraser’s recent biography in describing her as a frustrated, lonely, brave teenager who never ceased to be a child and achieved maturity just in time to die. The film is a grandiose, sometimes touching, sometimes indigestible mixture. Starting with Kirsten Dunst, a splendid actress, very touching in her openness (but does she know what it’s like to become a queen?) and the sleek, stolid Jason Schwartzman, a slacker-seeker now turned teenage king. Shot largely at Versailles, it’s lavish and authentic visually (or authentic-feeling; furniture and clothing had to be invented), but the film’s French characters speak in English and American accents and the musical background is full of Eighties pop. Fruit of a girlish fantasy, it’s a symphony of eye candy and real candy, bonbons and pinks and bright colors, a glorious superficial panorama that seeks to be a deep personal portrait of a tormented life.

Ms. Coppola would have none of the sepia tones of historical “Masterpiece Theater” productions; but this isn’t such a boldly original step as the film’s promoters imply and the director herself acknowledges a debt to Kubrick's Barry Lynden (and used the latter’s costume designer). Frears’s brilliant 1988 Dangerous Liaisons comes to mind, similarly light and bright. It’s also true that Marie’s somewhat crude dialogue suffers by comparison with Christopher Hampton’s sharp adaptation of Choderlos de Laclos. The talk in Marie is factual, or telegraphs information. The new film doesn’t evoke the wit and sophistication of the eighteenth century. The story, so detailed at first, seems rushed more and more as it goes on. But still it leaves you with something. And that something may be Louis and Marie going to bed – and nothing happening, night after night. They didn’t produce a child and maybe didn’t even have real completed sex for the first seven years. One comes to feel sorry for Louis too: there’s something helpless and sweet about Schwartzman that makes the seemingly odd casting eventually pay off.

Coppola negotiates a narrow line between spectacle and intimate story. Some of the moments are bombastic, as when the father Louis XV (Rip Torn) or some chief of protocol stamps a staff on the floor, reams of Manohlo Blahnik shoes or pretty pastries flow by our eyes, we get a vast panorama of Versailles or a huge elephant in our face, or a blast of organ music knocks us out of our seats. There are many royal eating scenes, the couple facing forward with vast symmetrical arrangements of food in front of them with the courses loudly announced, as in Rossellini’s La Prise du Pouvoir par Louis XIV. Unlike Rossellini, Coppola doesn’t strive for an alienation effect but wants us to identify with the fourteen-year-old Austrian girl from the moment she has everything taken away from her, even her dog, and is dressed in French clothes to meet the Dauphin.

We’re not very aware of the passage of time – Coppola’s movie tries too hard to avoid historical-film convention for that – but our heroine goes through some heavy changes. She drinks and takes drugs (what’s in that pipe the women pass we don’t know), she stays up all night, sneaks to Paris in disguise for a masked ball, squanders millions on landscaping (which merely embellished Le Nôtre's designs) and on clothes and gambles and wolfs down so many sweets you wonder how he could get into those tight bodices. She gets heavily into the Pastoral shepherdess scene and then has an affair with a sexy Swedish count, Axel von Ferson, played by Jamie Dornan, a former Calvin Klein model with long limbs and dreamy eyes, right out of a soap opera, or the cover of a pulp romance. The way the movie shows it, this indiscretion was soon over; weren’t there plenty more? Somehow there isn’t time to show, with all the costumes and bonbons. This is where the movie most falls short: on a sense of events unfolding outside, or even inside; it’s high on the emotions and the visuals, which never cease to be fun. Even when king and queen are driving away to be beheaded, Marie is looking out the window to admire the gardens. We get some court intrigue, notably conflict with Louis XV (Rip Torn)’s mistress Madame du Barry, played by Asia Argento as a vampire of a vamp. Ever present as a mean schoolmistress is the chief of etiquette, Comtesse de Noailles (Judy Davis), forever frowning and stretching her long thin neck. And Marie’s female play pals are lovely and cool.

Ultimately if all this elaborate stuff stands or falls with Kirsten Dunst, then it’s at least okay, because Ms. Dunst has innocence and freshness and aloneness about her, and she’s got the Teutonic looks Marie’s Austrian background requires, and young as she is, she’s got the energy and presence of an experienced actress. This isn’t a great movie but it’s a fabulous one. I dare costume-historical queens to stay away.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 09:41 PM.

-

NYFF Sidebar: 50 Years of Janus Films

50 YEARS OF JANUS FILMS -- A SPECIAL SIDEBAR OF THE 44TH NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

Kent Jones’s ringing introduction to Janus Films can be found online. The series runs Sept. 30-Oct. 26, 2006 at Lincoln Center.

Janus Films, "the preeminent distributor of classic foreign films in the United States for fifty years," was formed by Harvard friends Bryant Haliday and Cyrus Harvey following up on the huge success of their foreign film series at the Brattle Theater in Cambridge in 1953. Janus dates from 1956 with Fellini’s White Sheik and I Vitelloni. The thirty-film series at Lincoln Center includes Jules and Jim, The Rules of the Game, The Seventh Seal, Children of Paradise, Beauty and the Beast, The 400 Blows, La Strada, Wild Strawberries, The Seven Samurai, and L’Avventura. As these titles show, Janus has made a staggering list of foreign cinematic classics available in the US.

William Becker and Saul Turrell took over Janus in 1965 and in the decades that have followed has focused primarily not on presenting new films but on acquiring classics, preserving them, and disseminating them through theatrical and TV release and home-use formats. The Criterion Collection is also connected with Janus. Jones concludes: "American film culture without Janus Films is unthinkable. We’re celebrating their 50th birthday with a selection of titles from their extraordinary collection, all in brand-new or pristine 35mm prints. Janus Films is truly one of our national treasures. Here’s your chance to celebrate their achievements, and to be dazzled all over again by highlights from their incomparable collection.”

The Janus series runs from the end of September to the end of October at Lincoln Center. All thirty classics are in new prints. Judging by the two shown at press screenings, Polanski’s Knife in the Water and Ingmar Bergman’s Monika/Summer with Moinika (1953), the images are perhaps more pristine and beautiful than they even were when the films were first shown in theaters.

FROM THE JANUS SERIES; KNIFE IN THE WATER AND MONIKA

Knife in the Water (Nóz w wodzie, 1962), Polanski’s feature debut, made when he was twenty-nine, is a tense overnight sailing trip taken by a man with his pretty younger wife and a handsome young drifter they find hitchhiking on their drive to the boat. The action is claustrophobic and fraught with menace – the two men are in conflict from the moment they first meet – and a cool jazz score gives the film an edgy contemporary air. The young man carries a long knife of the switch-blade type. Does the old rule apply, that a weapon, once introduced in a story, has to be used?

Ingmar Bergman’s Monika (Sommaren med Monika, 1953), not his first -- he had made over a dozen films before this -- but perhaps his outstanding early work, is the story of two Stockholm teenagers, stock boy Harry (Lars Ekborg) and voluptuous, impulsive Mokika (Harriet Andersson), who meet and fall in love and run away for a summer on a motorboat on the Stockholm archipelago escaping from work and all responsibility. Monika becomes pregnant and they return to the city and marry – but things turn bad. This first powerful feature by the Swedish master is simple and sweet but nonetheless rich in emotional wrenching events. The film, which depicts teenage unwed sex, was shockingly sensual for its time. The intensity of Harriet Andersson’s uninhibited performance is still impressive.

The pristine look of both these new prints is astonishing and beautiful, particularly Gunnar Fisher’s cinematography in Monika depicting the fresh faces of the young lovers and the intense Swedish summer landscape.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 09:49 PM.

-

Weerasethakul's Syndromes and a Century (2006)

APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL: SYNDROMES AND A CENTURY (SANG SATTAWAT 2006)

Mysteries of reminiscence

More for the strictly arthouse audience than his previous Tropical Malady, the young Thai auteur’s latest is an impressionistic and disorienting series of scenes centering around several different hospitals, and focused on couples, romance, job interviews, and patients. There’s a singing dentist who serenades a young Buddhist monk in saffron robe whose teeth he’s working on. Later the dentist-songwriter is seen performing for an audience on a fairground stage. A sequence where a potential employee or medical school candidate and an older Buddhist monk are both interviewed by a young woman doctor is repeated in the film’s second half, with different camera angles and variations in the dialogue and the tone of the scenes. The film is split down the middle, though not as distinctly as in Weerasethakul’s two earlier films. The gentle dental work scene where doctor and patient share their dreams and passions is repeated, only this time the leafy trees and sunshine outside are replaced by a chilling white environment, a woman assistant is present, and no one speaks. Outdoor shots focus on wide country and city spaces, and on leafy trees seen from below with sky beyond. A young man who may have brain damage from carbon monoxide poisoning swats a tennis ball down a hospital corridor. The young man who wants to become a doctor now is one, in white coat, and stares sadly into space in a long static shot. An older woman doctor hides a bottle of whisky in a prosthetic leg and drinks to relax before her weekly appearance on public television. People talk inconclusively of reincarnation. There's a visit to an orchid grower, who buys an orchid from a hospital grounds, and is visited by a woman doctor in his study after he’s hung the orchid outside. All this would be annoying and disquieting were the scenes not so gentle, subtle, and evocative. Weerasethakul is an original, no doubt about that. His weddings of image and sound are sometimes numbing, sometimes subtle and enchanting, and always cryptic.

Very good -- as my Beowulf teacher, who happened to be Jean Renoir’s son, used to say after a passage of Old English was read -- and what does it mean? There's no simple answer to that. These are reminiscences, we're told (though not in the film itself), of the director's parents, both of them doctors; of their courtship; and of what it was like for him to grow up in the environs of a hospital. Weerasetahakul says that the first half, with its warmer, gentler mood, is for his mother, and the second, where scenes are repeated in brisker and cooler variations and the hospital is an antiseptic urban one, is for his father. Weerasethakul is a bold stylist and a confident setter of moods. But there’s not a lot to put together into a narrative, just a scattered set of observations. It’s a little bit as if you were watching Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi and Naqoyqatsi with tiny dialogue scenes.

The film lingers on long shots of exteriors, and glides back and forth in front of a large white Buddha. It returns to a room where prostheses are made and fitted to patients and finds the room filled with smoke (could it be the carbon dioxide the young man suffers from?) which is slowly sucked out by a large funneled pipe, while ominous mechanical music throbs in the background. Don’t worry about spoilers here. The ending, a large outdoor aerobics class, concludes and reveals nothing. Syndromes and a Century never unlocks its mysteries, it just casts its haunting spell and departs with a blacked-out screen.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 09:47 PM.

-

Todd Field: Little Children (2006)

TODD FIELD: LITTLE CHILDREN (2006)

Fine sexual drama with a small uncertainty of tone

Todd Field’s Little Children’s screenplay was written in collaboration with Tom Perrotta, on whose eponymous novel it’s based. Perrotta wrote Election’s, Bad Haircut’s, and Joe College’s funny, ironic screenplays before this. But though mildly satirical at times in its vision of middle-class white infidelity, this second film (at last) from the director of the powerful 2000 In the Bedroom, with its themes out of Cheever or Updike, also moves toward the solemn and the shocking.

One big reason for that is a second plot about a just-released sex offender and a troubled ex-cop who turns into a self-appointed protector of public morality campaigning to drive the ex-prisoner out of town.

Brad (Patrick Wilson) is a househusband caring for his little boy while feebly preparing for his previously failed bar exams. He has a gorgeous but emasculating wife, Kathy (Jennifer Connelly) who’s a successful PBS-style documentary filmmaker. Sarah (Kate Winslet), with an MA in English, in charge of a recalcitrant little girl with whom she has little patience at times, has a well-off distant husband (Gregg Edelman) who's a pretentious adman who gets off on Web porn. Sarah and Brad meet in a park where moms take their kids, in East Wyndham, Massachusetts. They wind up kissing when they first meet, mainly to shock the other moms.

Brad and Sarah spend a lot of the summer minding their kids together at the municipal pool. This turns into a torrid affair with frequent sex at Sarah’s husband’s large house. They're attractive, and attracted, and their general dissatisfaction with their spouses and with where they are now heightens their need to throw themselves at each other with the utmost abandon.

Meanwhile Ronnie (former child actor Jackie Earle Haley, vividly remembered from Bad News Bears and Breaking Away and strong in a new way here) has come into town: he’s the sex offender, a painfully self-aware one, and he lives with the one person who loves him, his aging mother Ruth (a convincing Phyllis Somerville), while the ex-cop, Larry (Noah Emmerich) wages his war as a one-man “committee.” Larry and Brad have met and Larry persuades Brad, who already wastes time watching boys skateboarding when he’s supposed to be boning up for the bar exam, to join a night touch football league team made up of cops – and thus the infidelity and the sex offender elements are linked. But they would be anyway, because this is a small community. And one particularly hot day Ronnie comes to the municipal swimming pool and causes an outcry when he’s spotted ogling young girls under water.

The other moms from the park, who were afraid of Brad and called him “the Prom King,” are gently satirized by a voice-over narration spoken by Will Lyman, of Frontline on PBS, which sounds like a high school educational film. Perrotta is, after all, a comic writer. But more of that later.

The movie has a bright, intense, clear visual style, sometimes making use of extreme close-ups. Since the acting and directing are fine, this gives things a feeling of authority. It's also effective in underlining both the satirical and the sensual aspects of the story, and heightens the emotional effect when the narrative lines move toward crisis.

Brad’s development (the novel-based voice-over tells us) may have been arrested by his mother’s dying when he was in his early teens, and this explains why he watches the skateboarding boys with such longing: they’re having the playtime that was stolen from him.

Another theme is that of Cheryl (Marsha Dietlein), Sarah’s friend and neighbor who baby-sits with her daughter when she’s having sex with Brad, speed-walks with her, and gets her into a book-discussion group leading to a pointed scene in which Madame Bovary is discussed and Sarah defends the adulterous heroine as someone who revolted in search of freedom. The older women nod approvingly, while one of the park moms doesn’t get it at all.

Partly because it’s hard to juggle all the elements in Perrotta's 350-page novel, the ironic narrative voice disappears throughout the film’s midsection.

At the end matters all come to a head, with Brad and Sarah, with Ronnie, and with his erstwhile nemesis, Larry, and a lot of tension is created through Hitchcockian cross-cutting between these climaxing threads.

Field has avoided the extreme finale of his first film -- this one shares such heavy concerns as families, infidelity, crime, and confronting death, but by contrast, this ending, though breathless and troubling, is ultimately sweet and marked by reconciliation and acceptance. One may wonder if underlying issues have really been resolved. The film feels somewhat overlong, but the nuanced characterizations and fine acting and the attractiveness of the central couple entertain and interest us mightily.

Perhaps the one weakness overall is a slight uncertainty of tone, which explains why some viewers are troubled by the voice-over (and also by its long disappearance midway). If situations are seen primarily as highly serious or even horrifying, it’s hard to see how the satirical feel fits in, and at the end we seem to have lost touch with where we started out. Ultimately as with so many American stories on film, the writers seem to have tried to tackle too much material. Nothing wrong with that, but they haven't quite got the world-view to encompass it all. Technically though Field has achieved more polish and shown more confidence, even compared to his already admirable and powerful first film of five years ago. The cast is wonderful, well chosen and well used. Field is an experienced actor: he knows the craft. This has got to be a film to think about at year's end when best lists are made up.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-25-2017 at 11:41 AM.

-

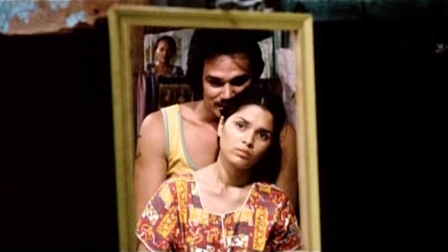

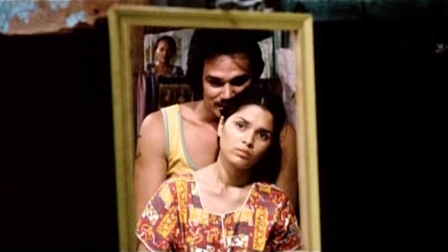

Lino Brocka: Insiang (1976)

LINO BROCKA: INSIANG (1976)

Classic Filipino mélo

Lino Brocka’s 1976 melodrama of slum family love double-crosses was the first Filipino film to be shown at Cannes and is being revived at festivals. It deserves to be seen for the female actors, mother Tonia (Mona Lisa, credible as an aging lady who’s still highly sexed and attractive) and gorgeous daughter Insiang (pronounced “Inshang”). Hilda Koronel, who plays Insiang, is enough like a Loren or a Lollobrigida to make you think of Fifties or Sixties Italian cinema and the visual style is conventionally of an early period, but this brutal story lacks the humanity and warmth of the Italians (and of other Filipino films, notably the current Blossoming of Maximo Oliveros). Tonia drives a family of in-laws out of her shack (which is in with other families; in this barrio there is no privacy and all is known) because she can’t feed them, but her ulterior motive is to bring in Dado, a handsome, macho man and a gambling no-good probably young enough to be her son, as her lover. Insiang has several young men (with big hair and bad clothes) interested in her, but the one she chooses is too cowardly and lazy to run away with her as she would like.

Soon Dado puts the make on Insiang. It turns out badly for just about everyone in this miserablist drama, which has been compared to Fassbinder and Sirk. Another reviewer has commented that the story undercuts the two major values in Filipino film – motherhood and the sanctity of the family. Brocka certainly keeps things lively, as do popular dramatic films from other Third World countries, and telenovelas. Yes, this holds the attention; but unfortunately the print used was an ugly-looking digital transfer that made all the boys look pimply and the shots look shoddy. Only Koronel’s lovely face shines through.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 09:53 PM.

-

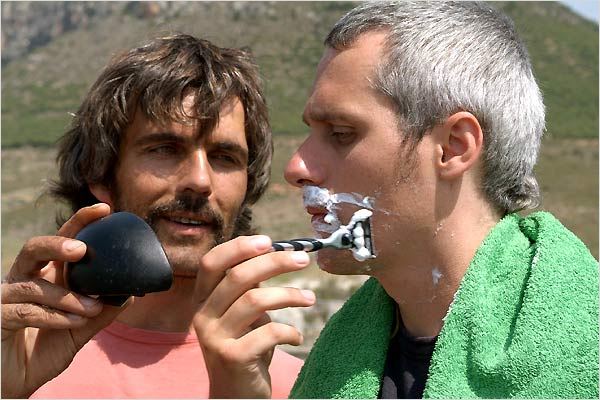

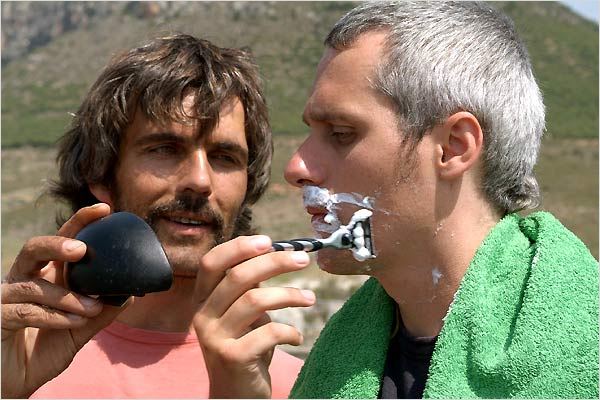

Marc Recha: August Days (2006)

MARC RECHA: AUGUST DAYS (2006)

Genre-bending Mediterannean meditation

In August Days/Dies d'agost Marc Recha has given us a sun-saturated Catalan documentary-style road movie that’s mostly a meandering improvised meditation on brotherhood and reclaiming the dead. The beautiful sometimes large-scale, richly atmospheric 35 mm. landscape images, nice soundtrack and Catalan-language narration are enchanting as a mood piece, if one is content with a trajectory that hasn’t much momentum and doesn’t lead anywhere in particular. Filmmaker Marc Recha and his non-identical twin David are the stars and the narrative is voiced by their younger sister. Marc had been researching the life of Ramon Barnils (1940-2001), a socialist editor who had been a family friend. He felt he was saturated with information and had to take a break. The break turned into making this film, which seeks to capture the mood of the interviews with Barnils’ associates, thoughts about the Spanish Civil War, the drought season they were experiencing, the rugged landscape, the Recha brothers’ affection for each other, swims and suntanned nudity and whatever characters or stories they ran into as they camped out of their van. This leads to pursuit of a giant catfish and the temporary disappearance of one of the brothers. In the end David has to go back to Barcelona to be with his daughter and Marc has to return to his project, and there it ends. I found it fascinating to listen to an extended narration in the Catalan language with its blend of Spanish and French-sounding words (perhaps linked with Provençal?). This isn’t a major film but it commands attention and makes sense as a film festival choice with its clean visual and auditory beauty and its way of playing around with genres and blending autobiography with fiction and documentary in a fresh and thought-provoking way.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 10:30 PM.

-

Alberto Lattuada: Mafioso/Il mafioso (1962)

ALBERTO LATTUADA: MAFIOSO (1962)

Sordi goes south

Italian cultural icon and cinematic great Alberto Sordi (1920-2003) was in peak form when he starred as Antonio Badalamenti, a Sicilian who’s become a successful FIAT executive and efficiency expert in Milan and goes on a two-week vacation to his hometown of Catanao in Sicily with blonde northern wife and two little blonde daughters. Laughs and thrills happen when they’re welcomed back into Antonio’s family – and the good graces of Mafia boss Don Vincenzo. It turns out Antonio not only owes the Don a favor for getting him the job up north, but is regarded by the local Cosa Nostra as a piciotto d’onore, a kid who distinguished himself in the ranks (maybe you could loosely translate the phrase “good old boy”) and he also happens to be the best marksman the town has ever known. What starts out as a broad comedy and a warm social satire on the Italian south turns more serious and intense as the hero fits right in and his initially standoffish wife starts liking the family and bonding with one female member whose beauty she’s able to bring out.

Fine writing, direction, and use of locations add up to a seamless film. You're never bored for a minute and most of the time you’re hugely entertained, so it makes sense that Mafioso is going to have a revival release in the United States. It’s unseen here, not on DVD and would be worth seeing not only for the fun it provides but for the display of Alberto Sordi’s range and fluency as an actor. Sordi starred in Fellini’s early pair, The White Sheik and I Vitelloni. Andrew Sarris has said Lattuada is "a grossly underappreciated directorial talent." Il Mafioso shows the writing skills of Marco Ferreri and Rafael Azcona, working with the team known as Age & Scarpelli (Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli). Their screenplay may be tongue-in-cheek, but it nonetheless provides insight into the Mafia, and the film's picture of Sicilian town life (in wonderfully rich grainy black and white, high style for the time) is vivid and authentic-looking and -feeling. Music by Piero Piccioni, another mainstay of Italian cinema (Il bel Antonio, Salvatore Giuliano, Una vita violenta). Produced by Dino De Laurentis with Antonio Cervi; this can also be seen as a product that reflects the energy and spirit of Italy’s postwar "economic miracle" period when so much was exciting culturally in the country – cinema, literature, design, fasion -- la vita, insomma.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 10:33 PM.

-

Manoel de Oliveira: Belle Toujours (2006)

MANOEL DE OLIVEIRA: BELLE TOUJOURS (2006)

Buñuel recollected in maturity

Pushing age 100, Oliveira shows he’s more than just keeping a hand in with this elegant Parisian drama starring cinematic veterans Michel Piccoli and Bulle Ogier, a meditation on the theme of Buñuel’s Belle de Jour that considers what might happen if two of its principals were to meet again forty years later. The focus is on Piccoli, who in the opening scene spots Ogier in a small concert hall when they’re listening to Dvořák. The handsome hall, seen in long shots, sets the formal, stately tone.

Henri Husson (Piccoli) pursues Séverine (Ogier), but she’s driven off quickly in an expensive black car. He then spots her in a chic bar (all this takes place in the 1ière and the 2ième, the chic heart of Paris) and again she escapes in the car, but he orders a succession of double scotches and the handsome young barman (played by Oliveira’s grandson, Ricardo Trepa) is very willing to talk and reveal Séverine is living in a hotel. There’ again a young desk clerk doesn’t hesitate to say which room the lady’s in, but M. Husson just misses her.

More heavy consumption of whisky and conversation with the young barman follows while a young prostitute and an old one (Leonor Baldaque and Julia Buisel) are always in a booth eavesdropping and commenting. Husson tells the story: how he urged a masochistic woman into betraying her husband over and over in order to enjoy his faithfulness, without ever telling him about it. The barman comments that this is the kind of story he gets to listen to quite often; the bar is a kind of confessional.

Eventually Henri manages to stop Séverine in front of a shop. She rushes off, but he gets her a gift there, a box. It’s the box with the buzzing inside of Buñuel's film, and later the couple eat in a private dining room – she arrives very late. It’s a formal, surreal ritual, in which Mme. sips champagne and M. pours down the scotch; they quickly consume three elegantly served courses without exchanging a word. She rushes off, and in her place a rooster appears in the hallway – a reference again to Buñuel and the surrealists. What does emerge before that is that Séverine is another person entirely now; that she regrets everything and considers entering a convent; and that Henri’s becoming an alcoholic he considers a kind of asceticism. The conclusion is bizarre, but there’s a strong sense, certainly appropriate for a director whose age leads him to contemplate death, of wickedness that has lost its interest and its sting. Certainly a unique product of a unique filmmaker. Paris at night is used beautifully in a way that avoids cliché. Piccoli in the larger role is mellow, as he is nowadays, and enjoying himself. Ogier seems appropriately in pain, and the once-chilly Deneuve character now engenders sympathy.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-24-2010 at 08:45 PM.

-

Hong Sang-soo: Woman on the Beach (2006)

HONG SANG-SOO: WOMAN ON THE BEACH (2006)

Sexual competition and creative malaise

Where Hong Sang-soo’s dramas differ from Eric Rohmer’s, other than all the ways that come with being Korean not French, is notably in the egotism mitigated by irony of having one of the main characters in his movies often happen to be a handsome, hunky famous director. In this one it’s a “Director Kim,” as he’s respectfully addressed (Kim Joong-rae, played by Kim Seung-woo) who goes to the somewhat sterile environment of the semi-deserted Shinduri beach resort on Korea’s west coast with his production designer, Won Chang-wook (Kim Tae-woo) in hopes of ending a creative block and penning the treatment for his next film. Won brings along a girlfriend, composer Kim Moon-sook (Ko Hyun-joung, a former TV star) and competition gets blatantly going when Director Kim takes Moon-sook aside and frankly says he’s interested in her and asks her whether she’d prefer him over the designer, given a free choice.

Joong-rae’s authority is underlined by his being older, better-looking, physically bigger and stronger-looking than Won, and possessed of a deeper voice. In comparison Won's a mild, slightly nerdy fellow. But despite that, Joong-rae’s not an out-and-out winner. He's comically chauvinistic in the way he damns the lady’s music with faint praise. And in the time that follows he proves to be neurotic and indecisive, stuffing his hands in his jeans and wiggling around on his legs with comic unease. Moon-sook’s dating men when living in Germany he admits is a turn-on for temporary dating, but the opposite for a long-term relationship. He has a serious hangup about mating with a woman who's experienced. Like a good Eric Rohmer character, he hesitates and they discuss. Moon-sook winds up saying that he's wonderful to her as a director, but in other ways just "a typical Korean man."

Hong’s stories often refer to sex and show couples in bed, but they aren’t erotic and characters rarely go all the way. Kim and Moon-sook do however begin with some long kisses on the beach that evening.

At another point Director Kim has a violent outburst of anger at a restaurant the trio enters because the owners are half asleep when they come in, and Chang-wook gets equally over-the-top in anger over the injustice of this and insists Kim must apologize. This seems random, except to show that both men have little control over their male egos, and tend to flail about, while the lady remains cool and composed.

In spite of all this Moon-sook becomes fascinated with Kim and they spent a night in an empty hotel room, but the next day Kim says it’s too quiet for him to work and they all leave Shinduri. Two days later Kim’s back on his own though, and leaves a phone message with Moon-sook, regretting his indecisiveness. He “interviews” a woman he runs into who “reminds” him of Moon-sook and takes her up to the same room he was in two nights earlier. Things get complicated when Moon-sook herself reappears and has a drunken emotional outburst outside the room. The new woman eventually feels hurt and abandoned too. In the midst of all this there’s a cute dog that gets abandoned by a mysterious couple, and Director Kim pulls an “unused muscle” and is temporarily disabled. Lots of snacking and drinking to a drunken state accompanies all these developments. By himself and with his leg semi-paralyzed Kim somehow turns out the film treatment. The relationships seem unresolved, but Moon-sook is by herself at the end leaving Shinduri again in her little car, which symbolically gets stuck in the sand and then gets out again so she can drive off on her own, free.

Woman on the Beach differs from previous Hong films in presenting its few main characters in the relative isolation of this new, somewhat drab resort during a cold spring season. The atmosphere is well used and the scenes are vivid. This film of Hong’s is perhaps even more inconclusive than most, and a bit long, but the rhythms of the conversations and the clarity of the blocking and editing arouse one’s admiration and this, like all Hong’s films, is original and watchable and will not disappoint his fans – which include the selection committee of the Film Society of Lincoln Center: they’ve been choosing his latest film as one of the NYFF's primary offerings every year for for four of the last five years. It's also true that Hong's improvisational way of working always results in fluid, convincing performances by his actors.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-20-2020 at 12:10 PM.

-

Jafar Panahi: Offside (2006)

JAFAR PANAHI: OFFSIDE (2006)

Soccer transcends gender restrictions

Jafar Panahi, whose previous films such as The Circle and Crimson Gold have seemed to range from dour to grim, has produced in his new Offside a funny, obstreperous, joyously chaotic ensemble piece that ends on a note of liberation and heartfelt fun – yet the movie deals with material quite as challenging and relevant as anything else he’s done. By focusing on a group of ardent girl soccer fans caught sneaking into the pre-World Cup Bahrain-Iran match in Tehran stadium where only males are allowed, Panahi brings up issues of national spirit and independent-mindedness, and the contradictions – and sheer absurdity – of the regime’s religious gender apartheid in a world of modern competition with a majority youth population and urban girls who increasingly think for themselves.

As the film opens we breathlessly join one of the girls in a bus, with a father pursing a lost daughter. This one has a disguise and has national colors as warpaint, but we cringe with her in the knowledge of what's going to happen: she’s still easily spotted. The thing is, most of the men around don’t really care. Still, rules are rules, and once they try to make it through the various checkpoints on the way into the big stadium the would-be soccer girls, or some of them anyway, get rounded up and held in a little compound upstairs in the stadium by some mostly young, green, and rustic soldier-cops who have no idea how to deal with these big city girls’ independent ideas and would rather be watching the game – whose roar we constantly hear in the background – themselves. Each girl is different – represents a different set of reasons for wanting to break the rules and different ways of doing it. One wore a soldier’s uniform and got into the officers’ section. One is tough and masculine and mocking and provocative (she could pass for a pretty boy, and teasingly hints at that: "Are you a girl or a boy?" "Which would you like me to be?"). One doesn’t care very much about soccer but went to honor a dead comrade. One (Aida Sadeghi) is an ardent soccer player herself – and so on. These Tehrani girls are stubborn and smart and they walk all over the uptight rural lieutenant in charge of them (Safar Samandar). One of the rural cops (Mohamad Kheirabadi) takes the girl soccer player to the men’s restroom (of course there’s no ladies’), forcing her to wear a poster of an Italian football star as a mask. A comedy of errors and chaos follows in which the girl escapes.

Later a spiffy looking van comes with an officer who directs the cops to take the girls to the Vice Department – violating sexual segregation rules qualifies as vice. A male gets mixed in with them – a kid who’s chronically guilty of smuggling fireworks into the games. The van turns out not to be so spiffy: the radio aerial is broken. But one cop holds it in place so they can listen to the increasingly heart-stopping reportage. Cops and prisoners are all joined in a common excitement now. There’s no score, the game goes to penalty kicks, and the winner will go to Germany.

In the background through all this is a real game, a real stadium, and real masses of young men crazy about the outcome of this event. The excitement is tremendous, and the streets are jammed with cars and flags and a milling mob of supporters praying for an Iranian win and united in their excitement.

What makes this film so good, as may be clear by now, is that it’s shot during the evening of an actual game with a real finale that turns everything around. This, in contrast to Panahi’s previous highly calculated narrative trajectories, is spontaneous vérité filmmaking that improvises in rhythm with a captured background of actual events and sweeps you into its excitement in ways that are quite thrilling.

The essence of Offside is the disconnect between modern world soccer madness and retro-Islamic social prohibitions repressing women – the latter existing at a time when young Iranian women are becoming part of a global world in which females participate in sport and share in the ardor of national team spirit. How exactly do you reconcile the country’s ambition to become a modern global power with social attitudes that are medieval?

A lot of Offisde is astonishingly real, including the way everybody tries to talk their way out of everything. The director’s decision to inject young actors into an actual sports mega-event leads to a stunningly effective blend of documentary, polemic, and fiction that is too energetic to seem to have a bone to pick, and that ends in a way that’s brilliant and moving.

I've had reservations about Panahi's films before, but this one kicks ass. Panahi does something remarkable here. He critiques his society, presents an unusual drama, and touches our hearts with a sense of a nation's aspirations.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-05-2025 at 10:33 PM.

-

Abderrahmane Sissako: Bamako (200)

ABDERRAHMANE SISSAKO: BAMAKO (2006)

Local color and argumentation in a passionate polemic set in Mali

As recently as Ousmane Sembene’s 2004 Moolaadé we saw a sort of African town meeting: such spirited democratic palavers are a feature of African local life. In Bamako, also known as The Court, Sissako has staged a mock trial of the IMF, the World Bank, and the other international financial institutions run by the rich countries that have perhaps contributed to the impoverishment and demographic ravaging of contemporary Africa more than they have helped the continent. This event takes place in the middle of a big busy square in a section of the capital of Mali, Bamako.

There is a whole panoply of characters – a beautiful queen bee (an example of the grace and poise of African women), Melé (Aissa Maiga) and her husband Chaka (Tiecoura Traore). Melé’s a popular singer whose marriage is disintegrating and two of her spirited songs are integrated into the film. People watch TV, and the director ironically injects into his film a “western” set in Timbukto, in which incongruous white men as well as Palestinian director Elia Suleiman and Bamako's producer Danny Glover shoot each other. The effect is grotesque, but that's the point: why should Africans be watching TV westerns? Elsewhere on the earthy “set” of the film there’s a young man, also beautiful, who lies dying inside a nearby building with no medical care. There are many children, some playing about, some being breast-fed. A couple marry, and the festivities interrupt the trial. There’s a flinty gatekeeper who decides who can come in and who can’t. There’s a traditional griot who’s one of the “witnesses” and who ends the proceedings with a hypnotic chant (not translated, but strangely stirring and stunning). There’s another “witness” – a former schoolteacher – so hopelessly demoralized he refuses to utter a word; a sound recordist; a video photographer who says he prefers to take pictures of the dead because they’re more real; and many authentic-looking extras, including a variety of dried-up tough young-old (or ageless) stick-men, all of them coming and going.

You get a vivid sense from all this, which is rhythmically inter-cut with the trial itself, of the harmonious seeming chaos of African village life; the color, the beauty and dignity of the people. You get above all a sense that life goes on. There are two white men on the “stage” of the trial, one an advocate for the international organizations (Roland Rappoport) and the other (William Bourdon) eloquently speaking for the African people and for socialism who concludes that the first world should be sentenced "to community service""forever." Eloquent though he is, a Malian woman lawyer who speaks after him (Aissata Tall Sall) is more touching.

Like An Inconvenient Truth, Bamako's trial presents facts and arguments of enormous present day importance – this time surrounding not global warming and the disintegration of the earth's eco-system, but another set of the planet’s major problems: the social imbalances, the domination of the many by the few; poverty and disease, “terrorism” used to excuse world domination, the richest nations' doing harm while seeming to do good; the ravages of globalization, the privatization of natural resources down to land and water, perhaps ultimately to air; the national debts of poor nations collected by the economic organizations of the rich ones, and thereby preventing the poor ones from gaining any ground against the ravages of poverty and underdevelopment.

This is powerful stuff. Sissako is, in theory, presenting both sides of the story, though it is obvious which side he is on and which side is in the majority onscreen. This is polemic. The international organizations obviously aren’t overtly setting out to destroy Africa – are they? It is preaching; but it is done in a rich and colorful and dramatically moving way. The film picked up a US distributor during the New York Film Festival. It’s not clear whether the way the print was presented was accurate. This seemed to be a projection of a digital copy that lost the surface beauty of the original. The colors of Jacques Besse's photography were beautiful, but dimmed. In French and Bambara (the Malian language).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-06-2025 at 08:20 PM.

-

Otar Iosseliani: Gardens in Autumn (2006)

OTAR IOSSELIANI: GARDENS IN AUTUMN (2006)

Jacques Tati without the punch line

Otar Iosseliani’s Gardens in Autumn is about the transitoriness of political power and the necessity of enjoying a simple life; it takes a cynical view of socialism and mob rule, and seems to advocate living quietly and unpretentiously outside the bourgeois mainstream (though an apartment in the middle of Paris is a perk not to be sniffed at, if available), having plenty of girlfriends, drinking a lot, and cultivating a panoply of colorful eccentrics as your friends.

The main character, Vincent (Séverin Blanchet), is a French minister of something or other, with a spendthrift wife; mass demonstrations lead to his ouster, and he is happier without all his possessions and his powers and his ruinously acquisitive spouse.

Michael Piccoli is in drag very funnily and successfully as the main character’s aging maman.

There are running themes. Certain animals, paintings and people constantly recur. Eet's all very surreal. Iosseliani is a Georgian (Russian) but this movie reflects a mellow director besotted with French culture, a French sense of comedy, often sans paroles (without words, as in traditional French cartoons) and reminiscent of Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot pantomimes. Unfortunately, there are words, and that spoils things, as does the repetitiousness of the narrative.

There’s much sweetness and mellowness here – but ultimately it seems to have fumbled the ball in its satire, which Tati never did. For those not tuned in, almost interminably long at a full two hours. That it is remarkable for its consistency of vision justifies its inclusion in the selective New York Film Festival, but it will not prove the most memorable of the NYFF 2006 list.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-17-2013 at 01:23 PM.

-

Stephen Frears: The Queen (2006)

STEPHEN FREARS: THE QUEEN (2006)

A tart tribute to two big Brits

Stephen Frears’ The Queen, written by Peter Morgan (The Last King of Scotland) and starring Helen Mirren, is a glittering, compelling, solemnly anxious news comedy about the week in late summer, 1997, when Tony Blair, fresh in office as new-Liberal Prime Minister, "saved" the British royal family, or saved it from itself, when Lady Di died in Paris. Partly the Queen, Prince Philip, and Prince Charles, all in their own ways, loathed Diana for what she had done to them, which the public, conditioned by the mass media to adore her, could not know about. Partly the Queen wanted to shelter the boys, Diana’s sons, from the noise of publicity, which would only aggravate their grief. Partly, and perhaps most of all, she was being the way she was raised, keeping things to herself, maintaining the immemorial English stiff upper lip. But also as Peter French has said about this film, the royal family "are shown to be morally and socially blinkered." Tony Blair reluctantly taught the Queen to see their absence of public response to the death, her insistence at first that it was a "private, family matter," was a disastrous policy that had to be reversed.

Diana had skillfully manipulated the media to form an image of herself combining Demi Moore and Mother Teresa. And she was still associated with the royal family, and appeared as wronged by them. You don’t turn your back on that. You eat humble pie and play catch-up. But a monarch isn’t tutored in such strategies.

No flag flew at half mast over Buckingham Palace, because that flagpole was used only for the royal flag, to show if anyone was home, and they were all at Balmoral, being private in their grief, avoiding publicity, and protecting the boys.

The Queen as seen here and imagined with enthusiasm by Morgan is not as witty as Alan Bennett’s Queen, in her last onscreen recreation, in A Question of Attribution (directed by John Schlesinger, 1992), nor does the estimable Ms. Mirren (who’s nonetheless very fine) have the buoyancy of Prunella Scales in Schlesinger’s film. But she is witheringly cold toward Tony Blair, all foolish smiles on his first official visit to the Palace. (Blair’s played by Michael Sheen, who’s experienced at this game.) As Peter Bradshaw wrote in The Guardian, "Mirren's Queen meets him with the unreadable smile of a chess grandmaster, facing a nervous tyro. She begins by reminding him that she has worked with 10 prime ministers, beginning with Winston Churchill, 'sitting where you are now'. As put-downs go, that's like pulling a lever and watching a chandelier fall on your opponent's head." And, of course, fun for us.

Fully recognizing the crucial importance of the British monarchy, this film is tartly reserved about both sides of the game. The royal family don’t like "call me Tony." And Blair’s wife Cherie is a bit ungainly in her blatantly anti-monarchy attitudes. But when Blair sees how Elizabeth’s coldness and invisibility is angering the fans of Dady Di – the media queen, the "People’s Princess" -- alienating her own subjects en masse, he steps in and persuades them to leave Balmoral and look at the thousands of flowers for Di piled in front of the Palance with their humiliating notes; then deliver a "tribute" to Di on TV. The formal grandeur of the film inherent in its subject matter – the Prime Minister and the royal family – is offset by its ironies and by the intimacy of the tennis match that develops in communications back and forth by telephone.

This movie is ultimately kind to Blair and to the Queen. It makes us feel sorry for Elizabeth, whom Blair comes to defend (against some of his cockier associates, not to mention his wife) with ardor. In Peter Morgan’s second imagined interview with Blair the Queen coolly observes that he confuses "humility" with "humiliation" (he hasn’t seen the nasty notes on the bunches of flowers for Diana); and she sees his kindness as merely due to seeing that what has happened to her could happen to him as quickly. As for Blair, the Brits may have little use for him now, but the filmmakers acted out of the belief that this week when he averted disaster on behalf of the monarchy was his "finest hour."

Frears has had a varied career, with high points second to few, concentrated in the decade of the Eighties after he came off doing a lot of television. These, his own finest hours, include the brilliant My Beautiful Laundrette, Prick Up Your Ears, Dangerous Liaisons, and The Grifters. For a while there it looked like he could do anything, then more as if he would; but he’s admirably willing to try new, as well as dirty, pretty, things. The Queen is dignified, but contemporary. It’s bustling and grand. Loud music and vivid performances help. Mirren’s Elizabeth is more of the Queen and less of the Queen than Prunella Scales’ briefer performance. Bennett’s Queen was very clever. Morgan’s is sad and noble. The Queen shows where the Brits are now, and the effect of Lady Di. QEII, like QEI and Victoria before her, has had an extraordinarily long and successful reign, half a century (obviously Mirren is younger than the actual Queen). But with these events, with this crucial week, the days of her generation essentially ended.

There’s a symbolic fourteen-point stag at Balmoral the men are interested in. James Cromwell’s brusque, lordly Prince Philip will do nothing but take the boys hunting, to get them outside. In the end a corporate banker kills the stag on a neighbor’s property, and only Elizabeth sees it, when she’s stranded in a jeep she’s driven into the mud, and crying.

For all its ceremony and noise, loneliness and wit, mostly The Queen simply tells a story, the new story of English royalty at the end of the twentieth century. It was a story worth telling, and it’s told well. A fitting opening night event for the New York Film Festival, in combines ceremonial elegance, good writing, and a superb lead performance by Helen Mirren.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-04-2018 at 09:04 PM.

-

Tian Zhuangzhuang: The Go Master (2006)

TIAN ZHUANGZHUANG: THE GO MASTER (2006)

A visual poem about an ancient game of competition and the pursuit of faith

Wu Qingyuan was born in China but has lived most of his life in Japan. Perhaps the greatest twentieth-century player of Go, the chess-like (but simpler and more ancient) territorial game of lenticular black and white stones on the grid square of a big wooden board. Wu was a Go prodigy, and his early victories led him to Japan at the age of fourteen. He dominated the game for over a quarter-century. This beautiful, sedately-paced film is based on his autobiography.

Tian’s film is very Zen. You will learn nothing about Go from it and little about Wu (known as Go Seigen in Japan; curiously as "Go-sa"—it makes him sound like "Mr. Go"). What you will get is a meditative but at times noisy visual poem starring the young Taiwanese actor Chang Chen, male lead of Hou Hsiau-hsien’s Three Times, focused on a stoical, restrained, silent man who with quiet devotion pursued the game of Go and Faith, those two goals of competition and the spiritual quest, and little else, all of his life, among all the physical and mental challenges he faced and all the events of a turbulent century. The stern, clean-faced Chang’s coolly intense performance, which rivets our attention at the film’s center at all times, is a milestone in his career and shows him to be one of the strongest new Chinese film actors today. Chang knew a little Japanese prior to filming but for Tian this project imposed the discipline of shooting in a language of which he knew nothing. But Tian had Japanese assistant directors and production assistants he trusted and as he said in an interview, "Go players don’t talk very much anyway." Nonetheless he acknowledges this was "very hard," similar to the problems faced by Hou in making Café Lumiere in Japan. Tian contemplated this project for a long time, and read Wu’s autobiography shortly after returning to filmmaking following the nine-year break that followed The Blue Kite. Tian knows his own hardships. The realistic portrayal of the long period of the Cultural Revolution, its prelude and aftermath in the richly detailed Kite led to his being barred from filmmaking for years by the Chinese authorities.

Wu lived in Japan during the unstable and violent Thirties and Forties. He was playing a tournament on Hiroshima when it was bombed. According to the film, the referee instructs the players to play on in the wrecked room. Wu suffered periodically from tuberculosis. Its residual effects exempted him from military service. He married a Japanese woman named Kazuko, who’s still with him (we glimpse the ninety-something, still vigorous Wu himself briefly at the film’s opening). Wu’s alive and well now, but in 1955 he was in a motor accident that caused him to stop playing. In his autobiography he wrote of this event that the God of competition abandoned him. Yet he still studies Go with passion.

The film is punctuated with titles denoting major events in Wu’s life, along with a statement from his autobiography. Wu’s pursuit of faith and search for relief from the intense mental stress of Go tournaments led him to join several religious cults, which are depicted in the film.

After Tian returned to filmmaking his first work was the relatively apolitical, Ibsenesque Springtime in Another Town. The Go Master might be a safe way of returning to politics and history, by approaching it through an apolitical man who lived in another country. But Tian never was never a stranger to controversy. His own vicissitudes and his growing maturity may simply have led him to respect a man devoted to the pursuit of inner goals.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 06-19-2009 at 11:19 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks