-

Oliver Assayas: CARLOS (210)

OLIVER ASSAYAS: CARLOS (210)

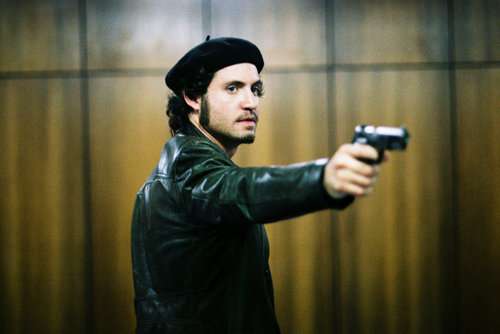

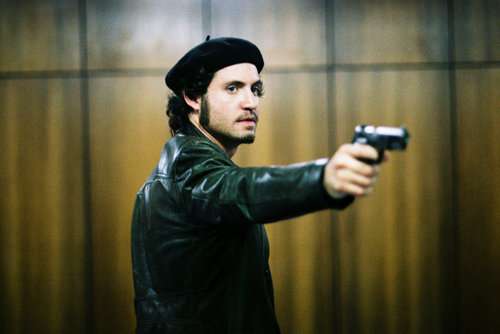

ÉDGAR RAMÍREZ IN ASSAYAS' CARLOS

Cool revolutionary terrorist mercenary seducer dude

The French director Olivier Assayas, former husband of the Hong King diva Maggie Chung, has made films as widely separated in style as Irma Vep, demonlover, Clean, and Summer Hours (fantasy, scifi, rehab, family drama). This year he has turned his talents successfully to the TV miniseries. Carlos, which is in three segments totaling 5 1/2 hours, is about the Venezuelan revolutionary Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, whose daring exploits made him into the media star who later became known as Carlos the Jackal. And the result is thrilling, informative, and fun.

Carlos has the many layers and multiple languages of the British series Traffik, but its subject matter, a succession of terrorist exploits with like-minded cohorts followed by flight and eventual capture, is closer to Uli Edel's recent feature The Baader Meinhof Complex. Except Assayas' focus is on one guy. And what a guy. Carlos, AKA Ilich, speaks Spanish, English, French, German and Arabic. He's dashing, super-macho, good-looking, brave, smart, and catnip to the ladies. He knows how to take charge, and he knows how to have a good time. The excellent cast is headed by Venezuelan actor Édgar Ramírez, who is more than equal to the task, as forceful with annoying cops and security officials as he is with OPEC honchos and pretty women. Much of the pleasure of the film is watching Ramírez in action.

Another pleasure is the authenticity. There are over a dozen national venues involved including France, Hungary, East Germany, Austria, Lebanon, South Yemen, Tunisia, Libya, Algeria, and Sudan, nine languages spoken, and there's never a false note. Though English is the main language heard, unlike the Hollywood version of such proceedings, Carlos is a film where Arabs play Arabs, and they have the right accents. It's enjoyable to see Ramírez sliding smoothly back and forth from German to French to Spanish to Arabic to English as the occasion arises. Ramírez' Carlos if not the coolest dude ever, comes pretty darn close. (Of course he is also a killer, and he suffers a decline.) This actor played in Soderbergh's Che but he didn't get to play Che, and that was a steal. What Todd McCarthy wrote was "Édgar Ramírez inhabits the title role with arrogant charisma of Brando in his prime." That's only a slight exaggeration.

Speaking of Soderbergh, though this sprightly study has none of the vanity project air of his Che, there is a similar problem of a format too unwieldy for theatrical viewing. This should be seen and is best enjoyed as TV drama in three spaced-apart segments. Instead it came out first at Cannes and was watched and reviewed there as a film. IFC in the US is to make it available in its full length and in a 2 1/2-hour shortened version. Critics who have to spend more than half their day watching one film, no matter how good, are likely to complain, and it's not surprising that some have knocked Assayas' extremely accomplished foray into the miniseries genre. Main points: that Carlos' ideology isn't subtle and gets cruder as he ages in the film; that he's crude with women too. Manohla Dargis wrote (from Cannes) that this Carlos is "a militant pinup" (she speaks of his leather and beret outfit for the OPEC caper) but at bottom is "a mercenary, a thug."

Yes, and one might add that the film could benefit from a few less scenes that begin with men lighting up cigarettes -- or cigars, even ones from Fidel's private Havana stock (as Carlos boasts at one point). The nicotine, not to mention the booze, consumption in this movie will wear you out.

I too had to watch the series in basically one long sitting, and that can leave you limp. It's still obviously great stuff; but being able to take a break of a day or a week between segments would make it work a lot better. Maybe in any format the free-lance revolutionary's life ultimately becomes repetitious and fatiguing. But this is a story full of panache. The Jackal has fed into many films already and is reputed to be a source of the Bourne concept, but it seems likely Hollywood will be moved to draw on the character anew after this dashing recreation, and Ramírez might get some plum roles.

Apart from his perhaps simplistic Marxist ideology and sexist dealings with Seventies women's liberationists, Carlos can be accused of being a grand-stander in tireless pursuit of personal fame. Various governmental adversaries or Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) handlers accuse him of such behavior. But despite his self-promotion, womanizing, and love of good whiskey and good cigars, the Venezuelan had lots of training, in economics as well as fighting, and his politics were sincere. He supported the Palestinian cause, and early on is reluctantly accepted by the PFLP's Wadie Haddad (Ahmad Kaabour) to carry out terrorist acts against Israel. This becomes his main focus, and leads to his pursuit by many national security services.

The film's first major scene is one in which Carlos is caught with a group of Latin American leftist friends in an apartment in Paris when two French DST counterintelligence agents come in looking for him. He shoots his way out and kills the two agents. This is the crime that leads to his incarceration in La Santé prison two decades later.

The second and longer big sequence is Carlos' most celebrated exploit, in which he and a group of German and Arab cohorts take OPEC's main delegates hostage at a meeting in Vienna in 1975 and try to fly them to Baghdad. The trip is cut short and is seen by the PFLP as a failure , but Carlos takes $20 million in ransom money and the exploit makes him famous. Ramírez's revolutionary outlaw shtick is at its most glamorous and sexy in these scenes. When he talks to the likes of the Saudis' Sheikh Ahmad Zaki Yamani as an equal, it's a pleasure.

Carlos is more effective than some of the other Seventies terrorism films at showing the range of human skills involved; they vary from the German nutcase Nada (Julia Hummer) to faithful allies like Johannes Weinrich (Alexander Scheer), to brilliant leaders like Carlos himself. Seeing this maligned profession from the viewpoint of a practitioner as bold, brave, and talented as Carlos allows one to understand better what it means to live this way. Carlos sees himself as a soldier of the revolution who exists only for his mission and his fellow soldiers. He is not a martyr but serves best by surviving for the next mission. He goes downhill in the end however, as he is rejected by one former Eastern Bloc and Arab ally after another.

The film contains the startling revelation that all countries use terrorists for their own ends. Carlos is traded back and forth from Yemen to Hungary to East Germany to France to Syria to Lebanon to Sudan. In the end he is abandoned by everyone, used up, and sold to the highest bidder. The process leading up to Carlos' delivery to the French is slow and torturous, but it is true. Assayas' Carlos is as instructive as it is entertaining.

Shown first at Cannes out of competition, later on French TV (Canal+). It was bought for US distribution in both short and full length formats by IFC. Seen and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. For more details see the Wikipedia articles Carlos (TV miniseries) and Carlos the Jackal. A.O. Scott has an profile of Assayas in the NY Times Magaine, "A New King of Cineaste," Sept. 24, 2010, which sets Carlos in the context of the director's whole body of work and personal identity.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-27-2010 at 09:28 PM.

-

Lee Chang-dong: POETRY (2010)

LEE CHANG-DONG: POETRY (2010)

YOON JEONG-HEE IN POETRY

A drowned girl, an elegant old lady, a search for beauty

As in his last film, Secret Sunshine, Lee Chang-dong has drawn an exceptional performance from an actress playing the role of a single woman raising a child under difficult conditions. Mija (Yoon Jeong-hee, a veteran actress in her sixties who had not made a film in sixteen years) is raising her teenage grandson Jongwook (Lee David). Her daughter has moved to another town after divorcing.

Three things are going on. And they are serious things, a death, a crime, and a fatal illness. A girl is found in the river. She was a student at Jongwook's school and committed suicide after being repeatedly raped by five students. One of them turns out to be Jongwook. Mija is an elegant woman who sets off her slightly ravaged beauty by dressing nicely. She has had a fascinating past, and evidently was once a beauty. Now, however, she is reduced to working as a housekeeper for M. Kand (Kim Hira), a well-off shopkeeper who is damaged from a stroke. Visiting a doctor for a prickly feeling in her arm, she is instead diagnosed as probably being in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Instead of pursuing treatment or telling her daughter -- about the Alzheimer's or, later, her son's crime -- she impulsively joins an adult poetry class.

Throughout the film, Mija struggles to produce a poem, taking out a notebook to jot down ideas whenever she eats a fallen apricot or sees a pretty flower. She also attends meetings of a poetry group whose contributors are alternately maudlin, kitsch, or bawdy. The bawdy one turns out to be a policeman, and that becomes significant later. And what is maudlin or kitsch comes across as colorful artifact, not in any way spilling over into a story that could so easily have succumbed to treacle but instead remains tart and keenly observed. Still, one wonders if the poetry class theme needed to be so exhaustively explored: at 139 minutes, the film is again too long, as was the 142-minute Secret Sunshine.

The crime is only revealed later after much time has been spent following Mija's daily routines, which include a relation with the post-stroke man that verges on the intimate, and a growing sense of her openness, patience, and ability to cope -- but also a tendency to walk away from unpleasantness. The rapes are to be kept secret but four fathers of the other boys corral Mija to contribute to pay off and silence the mother, a rough woman from a poor rural family, to the tune of 30 million won (about $30,000). She wants to contribute but hasn't got the money. The idea of a legal settlement and cover-up seems repugnant and Mija's solution is hardly above reproach either. Ultimately there is poetic justice, however, in more ways than one in writing by Lee Chang-dong, who began as a novelist, that is both subtle and ingenious.

Meanwhile Jongwook is never anything but oafish and lazy when at home with his grandmother, disrespectful, dirty, the basic teenager from hell -- but quite believable and never overstated. She is sometimes severe with him but still in some ways indulgent. And at moments he can be cowed into submission and still seem just a boy. Occasionally they play badminton in the evenings in front of the apartment building; she's rather good at it. Later she gives an awesome performance at karaoke. Eventually Mija will find surprising solutions to all her problems, and will be the only student who comes up with a poem at the end of the session as the teacher had requested. It is a poem linking her with the drowned girl.

Poetry has moments that are obviously pushed and manipulative and it is sometimes predictable, but it is also neat in its dovetailing explorations of morality, social justice, and the search for meaning and beauty in life. I tend to feel uncomfortable in Lee Chang-dong's films, as if something isn't quite right. However, watching Yoon Jeong-hee is a continual pleasure. Not only are her scenes delicate and subtle, but she is a wonderful example of how an older woman can be beautiful and elegant -- and dignified even under great duress. And sometimes manipulativeness is forgivable when the arrangements make as satisfying a pattern as they do here. And the best moments, like the visit by Mija to the drowned girl's mother, when she does not do what she was expected to do and instead the delicacy of the character portrait is enhanced, have an unexpected and quite wonderful quality.

Seen as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in September 2010. Shown at Cannes, where it was awarded the Best Screenplay prize, and at Telluride and Toronto with many other festivals to come. A Kino International release.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-21-2010 at 10:12 PM.

-

Michelangelo Frammartino: LE QUATTRO VOLTE (2010)

MICHELANGELO FRAMMARTINO: LE QUATTRO VOLTE (2010)

GIUSEPPE FUDA IN LE QUATTRO VOLTE

Pythagoras, transmigration, and Calabrian goats

Frammartino was born in Milan but again returns to his family's native Calabria, to which he had often traveled in his youth, for this second feature. He realized a dream: exploring the intersection of documentary and fiction, culture and history. Le Quattro Volte is a formally beautiful, rather abstract, almost wordless visual poem. The filmmaker visited the Serre, a mountainous region of the Calabrian outback in the province of Vibo Valentia. He found there communities of shepherds and coalmen and decided to make a film, having found his elements but not yet determined how they would fit together. He made a film about an old goatherd, a baby goat, a big pine tree, and an ancient process of making charcoal, the four "volte" or "times" referred to in the title.

The intellectual framework of the film is more elaborate and high concept than that. For Frammartino it's important that Pythagoras lived in what is now Calabria in the 6th Century BC, and that his school taught the doctrine of the transmigration of souls. Pythagoras wrote: "Each of us has four lives inside us which fit into one another. Man is mineral because his skeleton is made of salt; man is also vegetable because his blood flows like sap; he is animal inasmuch as he is endowed with motility and knowledge of the outside world. Finally, man is human because he has the gifts of will and reason. Thus we must know ourselves four times."

Open-minded viewers may enjoy just watching the handsome photography of a little-seen part of the world, with medium and long shots of landscape and villagers, and closeups of goats, nimble, pretty, ometimes comical, the sense of a quiet, seemingly unspoiled land, not unlike the Aquila of Corbijn's recent The American. On the other hand, notwithstanding the debt to Raymond Depardon and Robert Bresson, one may find Le Quattro Volte's total absence of plot or dialogue, the preponderance of inarticulate, neutral framing, either offputting, or just boring.

We begin, anyway, with the Human. The Shepherd (Giuseppe Fuda) herds his goats up in the hills and slopes above his village. He is ill, with a chronic cough. To treat it every night he drinks dust gathered from the floor of the local church mixed with water. Dirt not being an effective remedy for respiratory disease, the Shepherd dies: dust to dust. But in a striking shot from inside the marble tomb, there is still a heartbeat as it is sealed. The film moves immediately to the animal world, as a white baby goat is seen dropping from his standing mother's womb and slowly scrambling to his feet (an arresting sequence by any standard). Eventually a number of baby goats head out of the village following the herd up into the surrounding hills, but the little white one gets stuck in a long trench and becomes isolated. Eventually it runs up a slope and finds refuge under a big fir tree. From the Human we have moved to the Animal and now Plants take center stage.

Next, villagers are seen coming and cutting down the tall tree. Frammartino has explained that this is part of a local custom called Pita. They strip the tree, set it upright in the center of the village, and someone rides it over onto the street. A very long and typically static shot by excellent cinematographer Andrea Locatelli with his 35mm camera stationed high above a street shows men in costumes with the tree, a dog comically chasing back and forth around them and later causing a small truck to slip down a hill and bash down a fence. What the ceremony means is not explained, but we see Good Friday celebrations, with villagers recreating the Stations of the Cross, suggesting Resurrection.

Later the fir tree's cut into pieces and taken out of town to where the coalmen build wooden domes in which the wood is fired and turned into light, crispy black charcoal. Thus Human has gone to Animal, thence to Plant, now to Mineral. No dialogue, no music through all this, only the sounds of daily life, the tinkling of goat bells, roar of small engines.

As Jay Weissberg points out in his Variety review of this film, it's quite manipulative, making use of three villages to represent one, never showing signs of the presence of modern life -- pop music, television, cell phones. Things found in the remotest human habitations today are edited out to give a sense of primitivism and quietude. If this is truth, it's truth of a highly predetermined and honed-down kind. Due to the film's highly experimental nature its US box office potential may be dubious; but then Philip Gröning's nearly wordless 2005 monastery documentary Into Great Silence had a good US art house run. Le Quattro Volte's festival success is indicated by its winning the Europa Cinemas Label for Best European Film in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, and it received glowing reviews in Italy and went on to Telluride and Toronto, as well as the NYFF. US theatrical release will begin at Film Forum in NYC in March 2011. According to IMDb, it opened on eighteen screens in Italy March 28.

Seen as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in September 2010, this 88-minute Italian-German-Swiss coproduction is a Lorber Films release from Kino Lorber Inc. in the US.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-07-2017 at 05:33 PM.

-

Hong Sang-soo: OKI'S MOVIE (2010)

HONG SANG-SOO: OKI'S MOVIE (2010)

JUNG YUMI AND LEE SUN-KYUN IN OKI'S MOVIE

Shuffled film school triangle

Hong Sang-soo means philandering drinkers, egocentric filmmakers, pretty women, winter weather, and endless self-reflectiveness. This can lead him to good character studies, ironic laughs, keenly observed almost-real-time flirtations -- and to a light intellectualism and energetic use of dialogue that owe a clear debt to the French New Wave. This time, due to dividing the film into four short segments with the same triangle in rearranged situations, the repetitiousness and self-absorption are carried to an almost geometric extreme, and the situations, despite a Rashōmon-esque multiple examination, come through as thoughtful in a film-school sort of way, but otherwise only superficially delved into. Hong Sang-soo fans, who include myself, will still not want to miss this because it explores further themes already richly dabbled in by the filmmaker. Others may fail to be entranced.

Basically we get an older director and teacher and a younger one, and a pretty young woman film student; sometimes the younger director is just a student. In the first episode, A Day for Incantation, the tall, deep-voiced younger filmmaker Jingu (boyish Korean star Lee Sun-kyun, 35 now and so able to straddle the fence) is experienced and married; in later episodes he will revert to mere student status. Here, he has supposedly quit smoking and drinking but is slipping back, to his wife's disapproval. He discusses the decline of filmmaking in a bad economy with older film professor Song (Moon Sung-keun). He gets drunk and annoys Song with questions about a rumor that he's bought his tenure. Then he goes, drunk, to a Q&A following showing of a short film he's just made and he is called to task by a young woman for jilting her best friend -- in an affair even though he's married.

In the second episode, King of Kisses, Jingu is purely a student, pursuing Oki (Jung Yumi), another student, who rejects him for drinking and notes his classmates call him "psycho." But he proves himself a good kisser, and after staying up all night in the cold outside Oki's flat, she takes him in and has sex with him and agrees she's his girlfriend. She is probably having sex with Song, the professor and older man, at this time.

The very short episode After the Snowstorm is from the viewpoint of Song, here a disillusioned film teacher whose classroom after the snowstorm is completely empty. Finally just two students, Jingu and Oki, show up, and he engages in a question and answer session with them about life and love, firing off rapid, arguably superficial answers.

The fourth and titular episode Oki's Movie purports to be a movie made by and narrated by Oki, the girl film student, in which she depicts her two lovers, Song and Jingu, whom she accompanies on the same walk up Acha mountain in the wintertime a year apart, going back and forth between the two lovers and showing what the two lovers and she said and did at various points, the parking lot, the entrance, the pavilion, and how many times they went to the restroom on the way up. The gist is that she was very involved with both men at the same time, and felt herself to be equally in love with them both, but later dropped the older one.

There is a certain almost mathematical interest in the recombinations here, but the cutting up of the film into the four segments keeps any scene from being played through to the point of developing depth, a danger that has arisen in earlier Hong films, which are often divided into two or three parts set in different locations. I confess to a weakness for Hong Sang-soo through multiple Lincoln Center viewings, and can forgive him his greatest self-indulgence. But though aspects of the first and last parts of this film are memorable, I'm afraid this has the weakness of his earlier films in even greater measure: that they will be most enjoyable to watch for an hour or so, but afterward all that may remain are vague memories of blowhard movie directors getting drunk or laid -- usually both -- or standing talking on the beach.

Oki's Movie (Ok-hui-ui yeonghwa), a film of 80 minutes from South Korea, was seen and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, September 2010. It premiered at Venice several weeks earlier and also was shown at Toronto.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-21-2010 at 10:14 PM.

-

Patrick Keiller: ROBINSON IN RUINS (2010

PATRICK KEILLER: ROBINSON IN RUINS (2010)

An unsentimental journey around the south of England

Vanessa Redgrave voices the narration of this intriguing, intelligent film that hovers between historical analysis and geographical essay while traveling in an ellipse around the south of England with a series of static shots of locations that illustrate ecology, history, and politics in a world marked by the collapse of late stage capitalism, privatization of public lands (from the 16th century onwards), the emptying of the countryside, and planetary ecological disaster.

The framework is a fiction, separating Keiller (for whom this is the third in a series, the first two being London and Robinson in Space) from his observations, because purportedly the film is constructed from footage recorded by an alter ego, the wandering researcher Robinson. Robinson was not his real name, the narrator says. He had lived in Germany, though he was not German. The allusion is to the late W.G Sebald, a German writer long resident in England whose 2001 book Austerlitz this film resembles. At the end of the film, Robinson is said to have disappeared, but his footage found in a shed.

Striking images of nature and marginal sites (military bases, opium fields, lichen growing on a traffic sign) and sometimes contemplative, other times apocalyptic, observations are delivered in Ms. Redgrave's measured, pleasant, posh-sounding voice. As Keiller explained in an interview with Dennis Lim and other members of the press at the New York Film Festival, the filmmaking comes first in his process, and took some time. Then comes the writing, which weaves together (and paces apart) the different shots and interweaves information about little known historical facts and detailed accounts of the ownership of certain ostensibly public spaces. It's a given of Keiller's working method as a filmmaker and a thinker that he is simultaneously exploring the intersection of enclosures, lichen, the 2008-2009 global financial crises, while we may be looking at a marker showing 58 miles from London or a small ruined castle with a railway speeding by or a spider going round and round repairing its web.

Comparing Robinson in Ruins with London and Robinson in Space, Leslie Felperin of Variety feels the new film "hasn't quite got its predecessors' breathtaking range of reference or their spritely wit." He later describes the first film enticingly: "In the first, London (1994), an unnamed narrator voiced by the late Paul Scofield (whose droll, honeyed tones enhanced both pics so deeply) describes how he and his lover Robinson explored the burg of the title, from Downing Street, the prime minister's residence, to Ikea in deepest suburban Brent Cross, all part of a quest to map the 'psychic landscape' of the capital, with digressions about Baudelaire, H.G. Wells, and Laurence Sterne, among many others." That indeed sounds poetntially sprightlier than Robinson in Ruins, which does not much develop the Robinson character as it goes along or include digressions about quite such a range of authors but instead dwells a lot on US companies' and the American government's ownership or control of missile bases and other installations, sometimes in ruins, or abandoned after the recent expenditure of hundreds of millions of dollars. It seems agreed that viewers of Keiller's two previous Robinsons will get what's going on better, that there's less offhand wit this time, and that the replacement of the late Paul Scofield's rich, plummy, ironic voice by Vanessa Redgrave's is another loss. Nonetheless, though perhaps more downbeat than the earlier films and best taken in segments (which Keiller wants it to be via DVD, cued to a map), Robinson in Ruins offers lots of mental stimulation to the thoughtful viewer.

Keiller is a lecturer who took 13 years e to get from the last Robinson film to this one. He studied at the Royal College of Art, and has often presented his ideas and observations about architecture and landscape in gallery installations. Those, of course, could not include a narration as detailed as this one but are normally restricted to visuals. It takes a while to get used to the format. Clearly Keiller's films are avant-garde in nature. Felperin says these are essentially "radio plays with pictures." Thus the pictures distract from the words. But after one adjusts, the pictures provide a resting place for the eye while the mind is stimulated by the words. The images are coldly handsome: 35mm HD -- and suggest that despite the narrated decline of the UK and the planet, there remains much unspoiled beauty in England's green and pleasant land.

Seen and reviewed at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in September 2010. It was shown earlier at Venice.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-21-2010 at 10:24 PM.

-

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: UNCLE BOONMEE WHO CAN RECALL HIS PAST LIVES (2010)

APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL: UNCLE BOONMEE WHO CAN RECALL HIS PAST LIVES (2010)

Dying as a gathering of spirits

The 40-year-old Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who studied filmmaking in Chicago, is more and more celebrated in the festival circuit. His latest film, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, received the Golden Palm, the top honor, at the Cannes Festival this year. Shot in the environs of the director's hometown of Khon Kaen in Thailand’s rice-growing and poor northeastern plateau, Uncle Boonmee is a strange film that slides back and forth between present and past time and between dreamlike sequences involving visits from the dead and everyday silliness like a truant young Buddhist monk who says "Let's go to the Seven Eleven" or a dead son who comes back in the form of a wooly critter with red eyes that glow in the dark. Spiritualism, reincarnation, out-of-body experiences, visits from the dead, even sex with a fish come and go with a quality of dreamlike abandon that entrances those who surrender themselves to the director's vision -- and makes rational types go into total reject mode.

In one sequence Weerasethakul says is a homage to old Thai films a princess carried through the forest on a litter draped in diaphanous curtains walks into a stream beneath a waterfall casting off jewelry and clothing to be sexually possessed by a jumping (and hitherto talking) catfish that throbs between her legs.

Uncle Boonmee (Thanapat Saisaymar) is a character the director has used more than once. This time he is suffering from kidney failure, is obviously in need of dialysis treatments, and has left a hospital and come back to the family farm to live out his last days among relatives and caretakers, including his sister-in-law Jen (Jenjira Pongpas). Conversation is desultory, concerning Boonmee's need for care, a Laotian male nurse, and other topics. At a long dinner table sequence the phantom relatives begin to appear: Boonmee expects to depart this world, and they apparently come to see him off. First is his late, much-beloved, wife Huay (Natthakarn Aphaiwonk) in ectoplasmic form, a grayish image. Then comes his disappeared son, whom we've already seen as red glowing eyes in the forest. He's a furry "monkey ghost," a life-sized wooly mammoth. Everyone present sees these visitors. There's a contrast between the everyday chatty flavor of the dialogue and the supernatural, borderline horrific nature of the visitations. No one screams or shouts. Conversation is deadpan. This somehow works to create a surreal atmosphere in which anything may be possible, though to unsympathetic eyes the result may just feel peculiar and silly, or as one IMDb contributor said, "bizarre and little more." That viewer complained of losing two hours out of his life. Maybe so. But they may be two hours worth giving, because what Weerasethakul provides isn't something is best understood by description and analysis but rather must simply be experienced -- and in that it is distinctively cinematic.

The director's two previous films, Tropical Malady and Syndromes and a Century, were both divided into two parts with the second acting as a kind of commentary on the first. This just has sequences that move jerkily forward in chronological progression, sort of. How they connect isn't always wholly clear, particularly not in the case of the old Thai movie homage. Apart from the dinner table and the princess-and-the-catfish sequence there is a lengthy, later, climactic one, accompanied with an ominous throbbing sound, in which Uncle Boonmee and others explore a cave, their flashlights darting over its odd formations to create a succession of naturally spooky and mysterious images. This leads up to Uncle Boonmee's death. Somewhat anticlimactic is a closing episode of a funeral ceremony in a temple with flashing neon lights and female relatives in what may be a hotel room sorting funeral cash gifts and receiving the young monk, who sheds his robes, showers, and wants to go out and eat. The food run happens out-of-body. Uncle Boonmee also makes stunning use of suddenly introduced stills, some of them showing young men in camouflage-cloth fatigues gathered around the "monkey ghost" as if for a snapshot of comrades on an outing.

The world of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (or as some non-Thais call him, "Joe") seems largely not only alien and strange but also fey and self-indulgent, but nonetheless you have to grant that the director has natural cinematic gifts and his work is sui generis. His sense of composition, image and sound is very distinctive. Working with cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom, he provides many haunting images, especially in night photography. The sound here is a feast of powerful and rapid contrasts, between a chattering jungle and silence, a rippling waterfall and a saccharine Thai pop song. Somehow with rather limited means he creates effects that are rich and strange. This is not surprising. People can be spooked or scared or mesmerized better with limited means than the elaborate CGI of films like Inception. The costliest studio gimmicks merely call attention to themselves; the simple, cheap, but inventive ones focus on what the filmmaker wants to convey. This is why The Blair Witch Project was such a success. "Joe" is at heart a Blair Witch Project kind of guy. His weirdness is all the more weird because its framework is matter-of-fact, its means simple and DIY.

Weerasethakul's style appeals to a host of currently prevailing festival tastes. Glacially slow scenes shot with a stationary camera mostly with long and medium shots are much in vogue. So are fictions that are barely distinguishable from documentary. The more exotic the world thus evoked the better. And if the material provided is utterly puzzling, not much more is required. Especially when the gift for melding image and sound is personal and strong. Then we get a result that is not adaptable to mainstream general box office tastes. But what are festivals for if not to present films tailored to a very special audience, quite clearly distinct from hoi polloi?

Seen and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, September 2010. Winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes. There is also a 17-minute opening pendant film (like the one for Wes Anderson's Darjeeling Limited) called Letter to Uncle Boonme. The longer film is loosely based on a book by a Thai Buddhist monk. It is having some European theatrical releases. Also shown at Toronto, and the London and other festivals will show it. An article in the NY Times by Thomas Fuller, "Laurels at Cannes and Battles at Home," fills out the picture of the film's cultural context and the director's uneasy relationship with the mainstream Thai audience.

Uncle Boonmee will be Thailand’s Official Selection for Best Foreign Language Film for the 84th Annual Academy Awards. It opens in New York on Wednesday, March 2nd, 2011 at the Film Forum. Strand Releasing is the distributor.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-13-2010 at 03:12 PM.

-

Abbas Kiarostami: CERTIFIED COPY (2010)

ABBAS KIAROSTAMI: CERTIFIED COPY (2010)

The game of marriage, game of love

Kiarostami, the most honored of the contemporary "Iranian New Wave" directors, told an English journalist last year that he would never move from his native country. However, he has now directed an international film, produced in France (by MK2), starring a French actress (Juliette Binoche) and an English opera singer (William Shimell), shot in Tuscany, with dialogue in English, French, and Italian. And while the director, who made more than forty films at home in Iran and received many awards for them abroad, has been noted for unusual camera positions and confusing narrative gaps as well as harsh themes of politics and death, this new film is more of a glossy chamber piece. Except for a sequence shot into a car like ones he did in several earlier films, it's shot in a smooth, straightforward manner and depicts the story of a man and a woman who meet and spend a few hours together. She drives him to a touristy town called Lucignano. They argue, they drink coffee, they talk, perhaps they make love. And that's all there is too it.

Except that Certified Copy (Copie conforme is the original French title) is a teasing puzzle film that plays games with the theme announced in the title -- also the name of a book-length essay by James Miller (Shimell). He is giving a lecture (in English) celebrating the publication of the book in Italian. His thesis is that a good copy is as valid as the work of art it's based on and can give as much pleasure.

The weakness of this entertaining film, which includes a suave, if neutral performance by the opera singer Mr. Shimall (who never had a purely spoken part before), and a richly histrionic one by Binoche, who received the Best Actress prize for it at Cannes this year, is that it is all simply a conceit -- about identity. Viewers with a long memory will remember Alain Resnais' Last Year at Marienbad, in which a man meets a woman and claims they met there the previous year. The question is repeated over and over, and never resolved. The film, with its setting at an austerely grand old European spa, is a series of aesthetic delights, of pleasing abstract geometries. Certified Copy is something different -- but not entirely. Though superficially much warmer and without the austere elegance, it too is only a riddle.

The couple seems to be playing a game. There are many hints at the talk that She/Elle (Binoche) is a visitor who has heard of and seen this English writer and wants to meet him. She has seen and read his book, and so has her sister Marie. Her young son, to whom she speaks in French, seems to know she is interested in this Englishman and teases her about it. He too attends the man's talk, but is bored by it, perhaps doesn't even understand. (But does the audience? They are Italians.) She sends a note to Miller, and after an awkward meeting at her antique shop in the town -- later it emerges she has lived in Italy for five years -- she is soon driving him off to Lucignano in her car while he signs six copies of his book for her.

When they get to a cafe and Miller leaves to take a phone call, the mistress of the cafe has a conversation with her, in Italian, about marriage, assuming Miller is her husband. She takes up this game, saying they have been married for fifteen years. When Miller comes back she tells him, in English, about this. For the rest of the film she and Miller pretend to be a married couple. And they do it so well that we, the viewers, become increasingly confused. What is the game? That they are married, or that they were not married and are now playing at being married? And, in the terms set up (a little too neatly) by Miller's essay book, mightn't a fake marriage be as good as a real one? They seem to evoke the accumulated resentments and ill reproaches and indifference of fifteen years of marriage so convincingly. Little things cast doubt on the original situation, for example the fact that now, Miller speaks a lot to her in French, whereas at first they spoke only English. Shimell may be less of an actor than Binoche (one would expect so), but his mellow voice sounds like Cary Grant's and he has nice wavy gray hair. He's a nice posh fake husband -- or disappointing real one; take your pick.

The trouble with this, other than its being entirely contrived to puzzle the audience, is that it falls back on the essential fakery of conventional filmmaking, where well-trained (and well-directed and rehearsed) actors are able to play out emotional little scenes in a convincing way even though they often don't know who their characters are or where the scene will go in the final sequence of the edited film. Unfortunately films are too often just a game anyway; this is not particularly different. And Certified Copy seems false also in the way of an international production directed by a famous filmmaker from far away, with French, English, and Italian actors, glamorous accoutrements (a posh antique shop, nice car; a well-known writer who's just won a prize in Italy), posh voices, multi-lingual conversation -- so that, with the help of subtitles, we can enjoy feeling how international and sophisticated we are. Certified Copy is pleasant enough. Binoche, acting with equal fluency in English, French, and even Italian, gives a dazzling performance with emotional moments. But since the point is to puzzle us rather than move us, none of it seems to matter much.

Certified Copy/Copie conforme was seen and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. It premiered at Cannes, and opened the next day, May 19, 2010, in Paris; two days later in Italy. It opens theatrically in the US in March 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-10-2019 at 07:34 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks