-

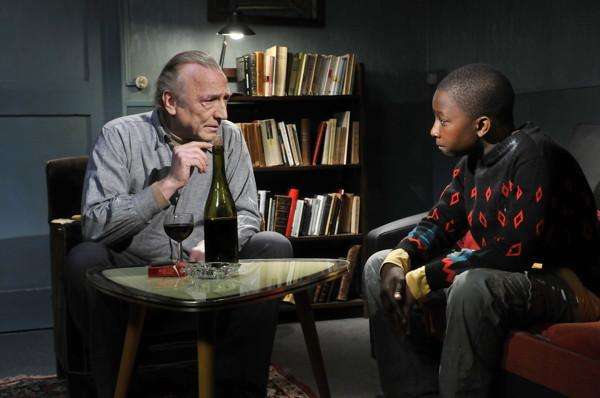

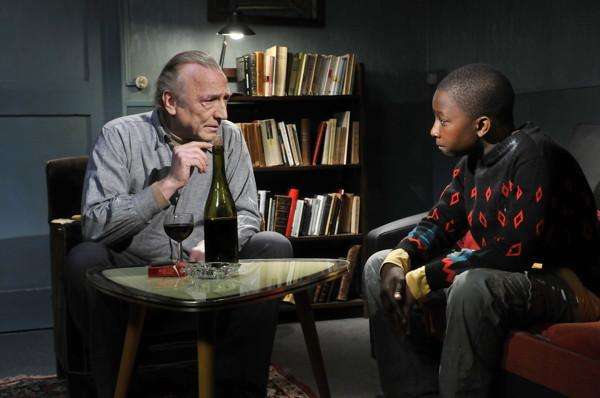

Aki Kaurismäki: Le Havre (2011)

Aki Kaurismäki: Le Havre (2011)

ANDRÉ WILMS AND BLONDIN MIGUEL IN LE HAVRE

Play that old tune again, Aki

Kaurismäki adheres strictly to his signature style here, the usual actors, the deadpan dialogue and sad sack characters, the bright colors, emphasis on blues and greens, direct lighting on actors, sharp images, ironically clear camerawork and editing. But there's something awry: the gloom is missing. The director has said he alwys wanted to have been born earlier to have been active in WWII resistance, and to evoke that, using many references to films of the period like Porte des Brumes and Casablanca and classic directors like Marcel Carné (references in the protagonists' names), Jean-Pierre Melville, Robert Bresson and others. But on its own terms, "Le Havre" is a continual pleasure, seamlessly blending morose and merry n, he filmed a story about a down-at-the heels Frenchman, reduced to shining shoes in the railway station, who becomes a clandestine working-class hero by hiding a young African illegal. For the dyed-in-the-wool Kaurismäki fan there are many little pleasures here but the big pleasure of bathing in a negativism so austere it makes you shiver -- that is totally lacking. Maybe the New York Film Festival jurors picked Le Havre because it's such a homage too French film classics. It's even got an aging Jean-Pierre Léaud in it, as a bad guy, an informer.

Kaurismäki's films always have an out-of-time retro style, which makes the evocation of the French resistance in a modern time setting not a stretch for him. He puts together one of his Finnish regulars, Kati Outinen, as the wife, Arletti, who takes ill but then miraculously recovers, and a French one, Andre Wilms, who was featured in three of his previous films, as the hero, Marcel Marx. Marx and a Vietnamese cohort are getting fewer and fewer shoe shining jobs since everybody is beginning to war sneakers. The camera opens up with a shot of arriving railway passengers' legs, all ending with sneakered feet. In a typically deadpan Kaurismäki sequence, one of Macel's customers gets gunned down after a shoe shine but Marcel only says, "well, at least I got paid first." Kafkaesque menace abounds here (with Kafka even red from to the ailing Arletti), but the horror is distinctly muted.

Hence when a container is found that's been left sitting for a week or two, and it turns out to have a group of African stowaways in it, they are all sitting around in the box, perfectly well, still, nicely lighted. One of them is a young boy, Idrissa (Blondin Miguel), who bounds out of the box and runs away. Marcel is destined to find him and save him and see that he gests to go to London where the waylaid container box was headed and where he has family. After finding him hiding in the water and bringing him food, Marcel protects Idriss at his house. His wife has gone to the hospital due to an undefined but possibly fatal illness (she never looks sick, nor will she allow the old, burt-out looking doctor to tell Marcel that it's serious). Idriss stays hidden without any problems, shining shoes or washing dishes when needed. He also speaks perfect French.

Marcel gets help from his shopkeeper neighbors, who forgive his debts more willingly now in complicity against the mean police. But nothing must help it, Marcel needs to raise 3,000 euros to pay a man to take Idriss to London illegally. To raise this sum he gives a charity concert. This droll event features an aging rock musican-singer with a puffy head of white hair called Little Bob (Roberto Piazza).

It's a pleasure -- chiefly visual, but otherwise cinematic -- to watch Kaurismäki at work. His bright colored yet restrained style, and his use of cameraman Timo Salminen and editor Timo Linnasalo show a look and rhythm that are elegant and consistent. Everything he includes in a film becomes Kaurismäki. And there are those that will like the director even more with an ubeat, updated theme. However, it's really not the same without the pessimism. Without it, the drollness loses its edge. Hard to see the point, really, or at least the necessity of showing this in as selective a film festival as New York.

Le Havre was included at Cannes and Toronto as well as the NYFF (and other festivals); it will be released theatrically in France, Sweden, and Slovenia in December 2011. Screened and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. Janus Films has acquired tis film for US release October 21, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:35 PM.

-

Nicholas Ray: We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011)

Nicholas Ray: We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011)

OVERLAPPING IMAGES FROM WE CAN'T GO HOME AGAIN

Shattered mirrors

It's for the experts, notably among them Jonathan Rosenbaum, to describe the relationship between this film by Nicholas Ray and his State U. Biningham students, and his wife, and its other versions and another film or other films that relate to it or grow out of it. The consensus is that the orginal We Can't Go Home Again was "finished" in 1972, and shown at the Cannes Festival in 1973. But it wasn't satisfactory, and it wasn't shown under satisfactory conditions, being screened at the end of the festival when everyone was too tired to take it in. There have been various versions since. This current new version, carried out under the supervision of Ray's widow (and fourth wife) Susan and completed this year under the auspices of the Nicholas Ray Foundation, The EYE Institute of the Netherlands, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive, adds new voiceover material provided by Ray himself replacing a student's voiceover, and there are other improrovements, notably a ditigalizing of the images.

We Can't Go Home Again is by and about NIcholas Ray and his film students in New York State at that time in the early Seventies, and all the things that were going on in their minds and in their lives at that moment, including their love affairs; the state of mind and professorial voice of Ray over ten years after stopping to make movies in Hollywood; the Vietnam War; the Seige of Chicago; the dynamics of a film class focused on making a film; and so forth.

To do justice to all this complexity, Ray and his collaborators use an interesting, alternately separate and overlapping, multiple screen technique. It's not at all a aslick, symmetrical split-image setup, but something more complex, sui generis, and expressive. The whole screen sometimes is used as a framework showing the Binghamton campus, with the various films the students shot set, small, a little to one side, within that big frame. Sometimes there are several or multiple frames in the big frame. Sometimes the film takes over the whole screen like a conventional motion picture. And the frames within the frame are of different formats. There are also different sound tracks that overlap while different frames are unreeling on parts of the big screen.

I liked this. It seemed a good way of capturing the effect of a chaotic collaborative effort. Ray himself dominates, along with several of the students, such as Leslie and Richard, a twenty-something couple who are both students in Ray's class. Ray is always puffing on a cigarette, usually wearing a black eye patch (though sometimes not, and once he's asked why and he says, in effect, that it just gets too damp and icky sometimes), and he's also seen wearing a red jacket.

Ray is wearing the red jacket, which Jonathan Rosenbaum says "inevitably recalls James Dean’s in Rebel [without a Cause]," in a long sequence out by a barn, where he goes aloft with a rope, aiming to hang himself, and in the course of botching the job, uttering the immortal line, ”I made 10 goddam Westerns and I can’t even tie a noose!" Ray doesn't die. He lived on to die of lung cancer in New York City in 1979.

It is essential to We Can't Go Home Again that it should be a mess and that it should have no definitive version. It's a monument to Ray's final years and to the sprirt of the early-to-mid Seventies. Ray had drug and alcohol problems; he later joined AA. He used drugs with his Binghamton students (it was the Seventies). The style of We Can't Go Home Again is very Seventies and very druggy. The film is also a remarkable expression of an intimate collaboration -- no doubt in a sense much too intimate -- between an arts teacher and his passionate young students, who challenge him in this film but also love him.

In his August 2011 discussion of this film on his blog, Jonathan Rosenbaum sums up We Can't Go Home Again using a comparison drawn from what for me is Ray's most haunting, and drug-trance-like, Hollywood film: "The multiple images that were combined via rear projection photography are often extraordinary, and the total effect of this graphic, innovative, agony-ridden document seems to be somewhere between the Guernica of disaffected America that it clearly aims for and the shattered bathroom mirror in which James Mason examines his fragmented features and identity in Bigger Than Life, his most disturbing Hollywood film. The dialectic between cracked self and atomized other is a central theme throughout."

This restored version of Nicholas Ray's collaborative We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011) was premiered at Venice and also included as a sidebar item of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in 2011. It was screened at Lincoln Center for this review, with a Q&A including Susan Ray.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:42 PM.

-

Alice Rohrwacher: Corpo Celeste (2011)

Alice Rohrwacher: Corpo Celeste (2011)

YLE VIANELLO AND ANITA CAPRIOLI IN CORPO CELESTE

Coming of age in Calabria

Italian director Alice Rohrwacher's debut feature is obviously not going to be just a a quiet, understated study of a pre-teen girl's first experiences of religion, a new environment, and sex, though of course those are heady topics anyway. That's clear from the opening scene, a hand-held depiction (shot by excellent French cinematographer Hélčne Louvart) of a realistically kitsch outdoor saint ceremony, complete with unappealing priest and recalcitrant speaker system, that is already something out of a latter-day Fellini. And where is all this happening? In a studiously rendered, newly rebuilt Reggio Calabria, which looks like a garbage dump and a highway, and whose newer church interiors look like cineplexes.

But tendentiousness is avoided by having everything that will follow filtered through the lens of almost-13-year-old Marta ( a limpid and picaresque Yle Vianello), the protagonist, who has recently been brought back to Calabria with her childish young mother Rita (Anita Caprioli) -- uisually exhausted from working at an industrial bakery -- and her annoyingly bossy and condescending 18-year-old sister after they'e all come back from ten apparently fruitless years in Switserland. It's Marta who get sent to a confirmation class to meet other kids and, I suppose, get with the local scene, in which a giddy pop, plastic version of catholicism is a central feature. "Seeing the Spirit is like wearing really cool sunglasses," is one of the slogans the kids are sold. Marta doesn't even know how to do the dign of the cross. But she's a quiet and perceptive child.

Rohrwacher, whose older sister Alba is a famous Italian actress, is content with crowded vérité sequences of relatives and neighbors and the jaw-dropping confirmation classes for a while. Pasquilina Scuncia is strong in these scenes as Santa, the unctious, goading teacher who's obsessed with the priest, whom she's either having an affair with, or would like to. But then the writer/director embarks on a lengthy fugal passage that touches some profound and shocking chords. Marta runs far out of town pursuing a man on a vespa who's been sent to kill some neworn kittens found in the churchand dump them in the river. So much for Christian kindness coming out of this church, which is big and ugly and has a futuristic neon cross of the altar that looks vaguely corporate and commercial.

Woven in and out of the whole film is the stunningly unappealing local priest, Don Mario, played by Salvatore Cantalupo, who in Gamorrah was the tailor who stupidly thought he could outwit organized crime. Don Mario is similarly doomed, and venial. He thinks he can force signatures from obedient parishioners to help get himself promoted to a more important church that might step him up to bishop. There is not one ounce of authentic religiosity in the quietly creepy Don Mario. Somehow he winds up finding Marta on her useless kitten-saving odyssey, and taking her along in the SUV when he goes to his village church to collect a large wooden crucifix, which is meant to be a central part of the confirmation ceremony that is to take place any minute. The crucifix won't make it. But while the priest isn't looking Marta gets to fondle the carved muscles of the wooden Jesus, her sexual and religious explorations momentarily dovetailing.

In the little church, grabbing the carved Jesis on the cross, Mario clashes with an older priest who might be his own father. Smoking a cigarette in the hurch the older man gives Marta a lesson about another Christ, not simple and good but misunderstood and angry. When Marta tells Don Mario about this Christ, it makes him run off the road and the wooden Jesus falls down into the river.

Outlines this way, these events may seem overly pointed, but Rohrwacher makes them work, partly by cross-cutting with preparations for the confirmation, which is supposed to take place now, and partly because everything is beautifully filmed. Don Mario is very late because he has stopped to eat a good meal in a seafood restaurant, while Marta stands around waiting. At some point in this extraordinary afternoon Marta has her first period. Maybe Rohrbacher loads her dice pretty heavily, but her use of the local trappings of modern, kitsch, uglified Calabria, her staging of birthdays and confirmation classes and creepy encounters with various church officials, not to mention the trip to the outlying town and the "authentic" older priest, as staged with great energy and assurance, Vianello, Scuncia and Cantalupo are all pretty memorable, and one has the feeling that Rohrbacher really cares about this stuff. The way things are lately, an Italian film this good is cause for celebration. The place and the child are quite memorable.

Corpo Celeste/Celestial Body debuted in the Directors' Fortnight at Cannes this year and is part of the main slate of the New York Film Festival, where it was screened for this reveiw. Film Movement has bought Corpo Celeste for North American release.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:46 PM.

-

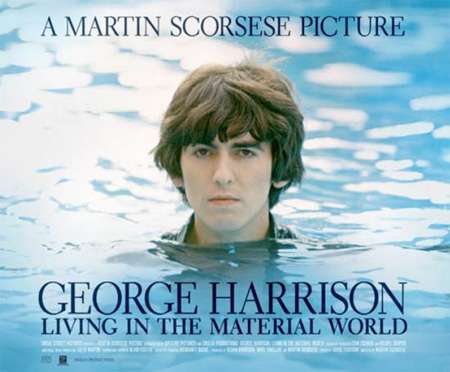

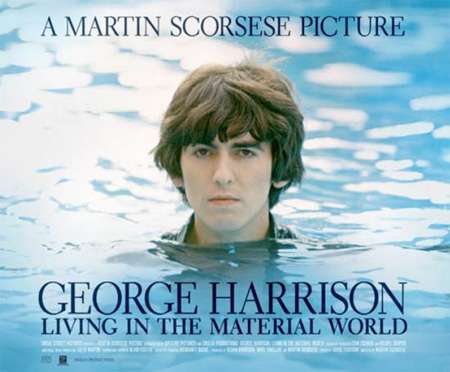

Martin Scorsese: George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011)

MARTIN SCORSESE: GEORGE HARRISON: LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD (2011)

Double biopic of the Beatles' seeker-guitarist

This HBO miniseries by Scorsese, which adds to a musical portfolio including a Rolling Stones concert (Shine a Light) and a Bob Dylan biography (No Direction Home) focuses on the other Beatle who isn't around any more, and perhaps the must mysterious and different of the four as well as ostensibly the one who most deeply sought to explore life's meaning. George is the one who was on a spiritual quest, and it led him to playing the sitar and meditation, explorations that changed the band's style and its members' behavior. Scorsese makes very good documentaries of the archival, illustrative, rather than investigative kind. It's an interesting paradox that a man in the middle of a media circus like George Harrison of the Beatles would go on serious search of inner peace and deeper understanding. Harrison explains this in a vintage TV interview. He says they found great material success early in life and so found out early that it was not the answer.

The Beatles must be among the most documented entertainers in history. There's no shortage of material, including plenty of interview footage with Harrison and people interviewed recently about him, like Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, later Eric Idle. But is this the way to get to the core of a life? Is this the way to get an insight into some of the most popular of all pop music? Scorsese provides a glossy survey, with great sound when the songs come (though they're not always allowed to run long enough) , and with plenty of sighs and gasps and chuckles along the way. And we have a good organizer: David Tedeschi, who edited Scorsese's superb Dylan bio, also did the editing here.

The film begins with Harrison's youth, then the Beatles' early days from Hamburg to the meteoric media rise, much of it narrated via letters home from George, writing to his mother. As Peter DeBruge of Variety points out, Scorsese assumes an audience already "up to speed" on the Beatles story and therefore does not bother to introduce some of the speakers till several hours in. Among the "many small details omitted along the way" is Stuart Sutcliffe, the band's lost bassist, not even fully named, and nothing much is explained about the Beatles' manager Brian Epstein till the moment of his death in his early thirties (also unexplained). Black and white still photographs are often beautiful, finely rendered, and introduced at just the right moment, but not provided with much context. Though this documentary (which runs to over three and a half hours) provides a wealth of material, it seems more celebratory than informative.

The key trajectory, of course, is Harrison's shift to eastern music and thought. There's more than one hint that LSD opened portals of perception that Harrison knew needed to be kept open by natural means. It's clear that Harrison became not just a pupil but a friend of Ravi Shankar. This orientalism led the Beatles to go from being the adorable pop band for screaming teenage girls through the Sergeant Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band to a Sixties and Seventies cultural icon worthy of endless interpretation and academic scrutiny.

Somehow George Harrison went from coolness and inner peace to far too many drugs and a burnt-out voice. The film doesn't offer anybody who can explain this. Could it be something it does describe, the fact that Eric Clapton went off with George Harrison's wife? The hard parts come in Part II. This is when 1970 comes, the Sixties ends, the group breaks up (nothing about the rift caused by Yoko Ono). Harrison makes his solo albums, gives the Bangladesh concert, gets involved with Monty Python and funds their Life of Brian, starts his own film production company, and moves to the giant Victorian mansion, Friar Park: the film turns personal, and ends with Harrison's stabbing and subsequent death from cancer.

After Lennon's assassination the film infomrs us how Harrison spent a lot of time preparing for death and in doing so managed to be in a state of relative wisdom and peace and positivity when the end came.

DeBruge argues that of all the Beatles Harrison is the most worthy of a detailed portrait because of the way he changed and sought answers to the deepest questions about life's meaning. But that is debatable. McCartney is the musical genius of the group. I personally would like to learn more about the music and how they made it, topics that seem secondary here, except for some good interviews with producers, including Phil Spector. And Lennon is still arguably the most charismatic and intellectually complex personality and, of course, he has been documented well already for that reason. I don't think this ranks with Scorsese's Bob Dylan biography; but it's not like you'd want to miss this if you are a Sixties or pop music fan. There is a handsome coffee table book to accompany it.

Screened for this review at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, in which it is a main slate selection. Also opens in the UK on October 4, 2011. The two-part film, 208 min total. US HBO TV premiere October 5, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:52 PM.

-

Lars von Trier: Melancholia (2011)

LARS VON TRIER: MELANCHOLIA (2011)

Alexander Skarsgĺrd and Kirsten Dunst in Melancholia

The party's over now

The mid-May screening of Lars Von Trier's Melancholia at Cannes a couple of days after Terrence Malick's Tree of Life inspired many comparisons by critics. Mike D'Angelo of Onion AV Club even went so far as to imagine it was as if Von Trier had seen Tree of Life and made a feature film in 48 hours as a "rebuttal" to it. Both films have a cosmic sweep and both focus up close on troubled families. Von Trier's beautiful prologue, with its figures floating in super-slow-motion in a dramatic dark landscape to the sound of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, as well as the much larger planet coming to splinter the earthn the second half, somehow together parallel Malick's images of orbs and galaxies floating through space balanced against his elder son brooding over and remembering his youth. If you play one film against the other the contrast in mood is as stark as the difference between Jessica Chastain's voiceovers about grace and affirmation in Tree of Life and Kirstun Dunst's declarations in Melancholia that the earth is "evil" and if obliterated will not be missed. Obviously Melancholia isn't a happy film. Dunst's Justine "knows things" and is sure there is no companionship or redemption awaiting us out in space (the recent sci-fi indie Another Earth notwithstanding). Tree of Life has doubts and sorrows too. One of its chief playbooks is the Book of Job. But it's also full of a sense of imminence and awe.

These are both grandly ambitious, strong, beautiful films, among the year's best. They also differ hugely, apart from mood, in their ways of looking at time. Tree of Life gazes continually backward. Melancholia stares numbly upon the present, with only occasional quick terrifying glimpses into the future. As we wait and wait upon a bride whose growing depression slows her to a halt, the film delivers a palpable sense of drawn-out real-time present. As it ends, the future becomes now, and never.

Such comparisons aside, emotionally and artistically Melancholia initially has much in common with Von Trier's previous film Antichrist in having emerged from the same period of profound depression the director was going through. But Melancholia goes to fewer extremes as provocation and departs less from "reality." Melancholia has provocative moments, but its horrors, however posh the staging, are closer to the everyday experiences of anger, selfishness, and recrimination. The new film has an obvious direct kinship with with Thomas Vinterberg's 1998 The Celebration, "the first dogme film." The Celebration focuses, as does the first half of Melancholia, on a large and festive gathering of a family whose leader is a titan of business. Vinterberg's focus is a birthday, Von Trier's an expensively staged wedding party: both lead to public accusations and verbal fighting and a general degeneration of what was to be a festive event. Moreover though Von Trier's staging is infinitely more grand (and, considering the film as a whole, more beautiful), except for during the opening slo-mo sequence he uses the same constantly swinging, jittery dogme-style camerawork throughout Melancholia, as if to link his grandiose, epic present style with his more Brechtian dogme roots. (He has said that the cinematography in Antichrist came out to be more beautiful than he originally intended.)

Melancholia is operatic in its production even to its theme music, and feels close to something like Patrice Chéreau's last great film success, the 2005 Gabrielle -- Chéreau being literally one of the great designers of European opera productions. At the same time the epic emotions have a strong physicality through the closely filmed stars, John Hurt as the frivolous but sympathetic dad, Charlotte Rampling as the cruel, blunt-spoken mother, Kiefer Sutherland as the materialistic brother-in-law, above all Charlotte Gainsbourg as Claire, Justine's "normal" sister. Gainsbourg has become a Von Trier regular. Her casting here doesn't seem quite right at first, but the point may be to make the sisters reflective opposites who are partly interchangeable. Dunst, the depressive, seems superficially down-to-earth and strong, and becomes the solid one as the apocalypse draws near, while Gainsbourg, the more positive and sensible of the two sisters, is wispy and gray and has an air of melancholy about her, of the sad, sullen striver, and as chaos approaches she wilts. The contrasts are really not quite that easy, either, but roles do subtly reverse as doom approaches in the film's second half. To play Michael, the groom, Von Trier has chosen the tall heartthrob (and TV vampire) Alexander Skarsgĺrd, fresh, blooming, and cheerful. Udo Kier, in fine form, is a semi-comic wedding planner who becomes so furious with Justine for ruining the event, he refuses to look at her and averts his gaze or covers his eyes in her presence. Wedding planners the world over can doubtless relate. Despite its lugubrious pace the first half of Melancholia is full of little comic touches that signal that this is somehow one of Von Trier's least harsh and provocative films.

The first, "Justine," half of the film shows the bride gradually more and more obviously alienated from her sister, her new husband, her boss and her parents. At some points her negativity seems excessively schematic and Brechtian, but Kirsten Dunst, who won the Best Actress award at Cannes for this performance, is convincing and natural and awakens sympathy -- as well as impatience. Justine gradually drifts away from the party and becomes increasingly sad and desperate during the night. Many of the guests and even the sisters' father (John Hurt), whom she begs to stay, go home, the groom himself departing with astonishingly little protest -- perhaps so well aware of Justine's emotional issues he half expected this debacle all along.

The second, "Claire," half stays at the castle where the party took place, also the home of Claire, her husband John (Sutherland) and their little boy, Leo (Cameron Spurr). The mood is more intimate but attention now shifts from individuals to the firmament. The mysterious orb in the sky is now revealed to be a planet approaching the earth. John, perhaps to maintain family order, holds to the declaration of some scientists that the planet will pass by without trouble. But Claire finds an online counter-story that describes the two planets' approach as a "Dance of Death." She is printing it out when the electricity dies and everything shuts down. The rest becomes a quiet, internalized allegory of the end of the world that is haunting and beautiful. Wonderful use is made of horses in the stable that Claire and Justine go out riding on (till Claire won't or can't), become violently troubled as the firmament is disturbed, and then grow ominously calm.

Melancholia gives one much to chew on, and chewing is possible because the material is quiet and Bergmanesque, lacking either the high-handed indictments of America, the sexual extremes, or any of the usual Von Trier provocations, but richly displaying the director's gifts as a maker of complicated dream worlds with telling parallels to our own experience. The final sequences have something in common with that most depressing of all movies, Michael Haneke's The Seventh Continent, but the beauty and grandeur give one a far different sequence. Besides, these people, though the depressive, deeply pessimistic Justine may embrace it most readily, do not choose extinction as does Haneke's little suicidal Austrian family: they merely prepare and wait for it. Von Trier's art house strategy is so cunning that his world ends neither with a bang nor a whimper. The final shot simply explodes in our own heads. The director has given himself a hard act to follow this time. His blend of science fiction, social commentary and psychological study, presented via superb cast and striking mise-en-scčne, adds up to high cinematic pleasure, despite the dark matter.

Melancholia debuted at Cannes May 18, 2011. It has been included in other festivals, including the Toronto and New York. Following VOD Oct. 7, limited US release by Magnolia Pictures begins November 11. Included in the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center and screened there for this review.

*A web page: "Malick vs. Von Trier@Cannes: http://blog.uvm.edu/aivakhiv/2011/05...-trier-cannes/

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-30-2014 at 11:03 PM.

-

Béla Tarr: The Turin Horse (2011)

BÉLA TARR: THE TURIN HORSE

ERIKA BOK IN THE TURIN HORSE

Imagination dead imagine

The Hungarian director Béla Tarr is not for everyone. His style is distinctive. HIs venue is the film festival. He works in black and white, and at length. Great length. The subject is often people in remote places oppressed by dire weather. One of his masterpieces is Satantango (1994), about a village whose inhabitants are squabbling over cash: it's seven and a half hours. Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) concerns a town oppressed by frost, and villagers gathering outside a great exhibit of a whale carcass. Two and a half hours. The Turin Horse, which he declares will be his last film, also two and a half hours, concerns a bearded man, his dreary granddaughter, and a flea-bitten workhorse. They are out in the middle of nowhere, their primitive house and stable surrounded by howling winds. A dust storm rages, with a background of grinding strings swirling over a repeated cluster of notes.

The pretext for The Turin Horse is an apocryphal story of Nietzsche in 1889, when he saw a cabman abusing his horse and intervened, throwing his arms around the pathetic steed. We know what happened to Nietzsche, but not what happened to the horse, says the film's intro. Tarr endeavors to correct that with six days in the lives of the cabman Ohlsdorfer (Janos Derzsi), his granddaughter (Erika Bok), and the poor beast. Tarr tells a tale of daily rituals, suffering, darkness, and attrition. Gypsies raid the well, and later it has gone dry. Deprived of water, Ohsdorfer and granddaughter pack up essentials and leave, pulling a cart. The horse, which has lately refused to move or eat, accompanies them. But a day later they return and unpack everything. Eventually the winds stop, but the lamps won't light, and the embers die out: no more fire or light. And still no water. Only liquor.

Ohsdorfer and the woman are like Hamm and Clov in Samuel Beckett's Endgame without the wit and glorious language and cosmic setting. This pair hardly talk, and when they do, they speak in grunts and expletives. The granddaughter helps Ohsdorfer dress and undress, gets water (when there is any), tends to the horse (perhaps), boils potatoes. One big potato each is their sole meal, eaten off a crude dish without utensils. When they have come back from their attempt to escape, Ohsdorfer sits and looks out the window. His granddaughter eventually stops eating. The horse looks bad, but is still alive.

The Turin Horse is an exercise in style and mood. It tells us nothing, but its slow movement and dark look stays with us after the film is over. None of this would work without the grinding cellos and other string instruments underlining everything with a sense of grim, noble determination.

Gus Van Sant has cited Béla Tarr as a "huge influence" on his later, more arthouse work, beginning with the slow-moving and stark Gerry, which concerns two lost young men in a desert wandering about hopelessly. Tarr takes us back to the primitive roots of film. But is he a good influence or a bad one? The Turin Horse is one of Tarr's grimmest, most minimal films. It seems to illustrate Samuel Johnson's motto uttered in Rasselas: "Human life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured, and little to be enjoyed." Here, we don't get the benefit of Beckett's cosmic jokes, not in so many poetic words, anyway. Of course The Turin Horse, which also has a visitor whose monologue provides an indictment of the villagers and perhaps all humankind, but one that Ohsdorfer dismisses as sheer bunk, is full of symbols one can while away many delightful hours in interpreting.

Tarr is a metaphysical visionary whose viewpoint is very distinctive. The technical aspects of his films are impeccable. This film was shot in handsome black and white by cinematographer Fred Keleman (who also did The Man From London, NYFF 2007), distinctively scored by Mihály Víg and co-written by longtime Tarr collaborator László Krasznahorkai. Each "day" consists of a very few long takes, which are enlivened by Tarr's technique of following his characters around the convincingly weathered hovel (designed by Sandor Kallay) with a Steadicam.

The Man from Turin has been shown at major festivals, including Berlin (where it won the Silver Bear), Hong Kong,Moscow, and Toronto, and the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. The Cinema Guild acquired U.S. distribution rights and plans to release the film theatrically this winter.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2011 at 09:31 PM.

-

Abel Ferrara: 4:44 Last Day on Earth (2011)

ABEL FERRARA: 4:44 LAST DAY ON EARTH (2011)

WILLEM DAFOE AND SHANYN LEIGHT IN 4:44 LAST DAY ON EARTH

Gore was right: let's talk on Skype

It's an ecodisaster: Gore was right, talking to Charlie Rose. So was the Dalai Lama. So were various other people seen on TV randomly in Willem Dafoe's loft apartment in New York as he hangs out with his girlfriend and talks to various people on Skype and in person, skipping over fire escapes to peek in on some friends whom he hasn't seen for some time.

The girlfriend paints bad Jackson Pollack knockoffs as they wait for the end. A TV anchorman excuses himself to go home to be with his family because, you see, this is the last day on earth. It's all going to explode, or something, later.

When you know the planet and all living things are finished, what do you do? Probably not spend your time with Cisco (Dafoe), a nervous worrier with nothing particularly interesting to say, or his young girlfriend Skye (Shanyn Leigh, the director's girlfriend), an insecure lass in pink silk pajamas (she later changes to a small dark dress) with artistic pretensions and jealous feelings toward Cisco's ex. One of the difficulties with dramatizing their efforts to make things right before the end is that we know little about them and less about their friends and family. For example, when Cisco arrives at his friends' apartment via fire escape and spends a little itme talking to them, we never quite learn who they are. There's a discussion of whether a man long in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction would want to go back to using now, since it's all over, so to speak. He doesn't. He wants to see the big bang bright and clear, not numbed by substances. Cisco isn't so sure. He thinks if there was ever a time to get high, it's now. This is a discussion that anyone in recovery would be familiar with.

Most of the screen time is spent at Cisco's loft studio apartment on the lower east side, where very little is happening, except for the mutimedia display provided by Ferrara's setup of computer, big screen TV, iPad, and other gadgetry. Cisco and Skye take refuge in sex for a while, which involved an up close squence of him caressing her naked arse and thighs that is very uncomfortable to watch. Again, the Skype farewells, when Cisco's to his ex-wife causes Skye to scream and grab Cisco and the laptop. Rarely have we seen such a dramatic Skype exchange. Come to think of it rarely have we seen so many Skype conversations in a film. The best Skype moment is provided by a Chinese food delivery boy who asks to Skype his family in China. We don't know what they're saying -- no subtitles are provided -- but when he kisses the screen, closes the laptop, and kisses it, then walks out bowing after his hosts have hugged him and given him money, it's clumsy, but also quite touching. Skye is prompted to appeal to her mother, also on Skype. In this role Anita Pallenberg briefly provides some European maturity and good taste.

Ferrara hits his technology/media theme hard, but not to great benefit.

This film looks pathetic when one has recently watched Part II of Von Trier's Melancholia, which achieves grandeur and solemnity with a similar theme. Ferrara's film suffers not so much from a lack of budget as from a lack of vision, lack of explanation for the apocalypse, lack of structure for the story, lack of plot and lack of interesting dialogue. Ferrara delivers a positive message about reuniting with loved ones at the end, but the context never gives it an emotional punch. There's a disaster here, but it's not the plot, it's the whole movie. 4:44 is as unfortunate as the selective New York Film Festival's main slate choices ever get.

Ferrara has his devoted fans, some of whom seem to be members of the New York Film Festival selection jury. His Go Go Tales, not appreciably better than this, was part of the 2007 NYFF. Ferrara at his best, as in King of New York (1990, with Christopher Walken), Bad Lieutenant (1992, with a fearless Harvey Keitel), and The Funeral (1996, again with Waken), is always chaotic, but the chaos in those films contains solid meat you don't find here. Fans will be glad that after a long break the director returns to his native NYC, but the film doesn't open up enough to make good use of the location. This time the chaos just seems like diffuseness, and even certainty of imminent death fails to focus the characters' thoughts sufficiently.

4:44 was shown at Venice and, as mentioned, the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. It will be released commercially by IFC Films.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-27-2011 at 07:45 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks