-

New York Film Festival 2011

MISS BALLA, Gerardo Naranjo

New York Film Festival 2011

Welcome to Filmleaf's Festival Coverage thread for the 49th New York Film Festival, fall 2011, put on by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. The site's General Film Forum discussion thread for the NYFF begins here.

INDEX OF LINKS TO REVIEWS

4:44 Last Day on Earth (Abel Ferrara 2011)

Artist, The (Michel Hazanavicius 2011)

Carnage (Roman Polanski 2011)

Corpo Celeste (Alice Rohrwacher 2011)

Dangerous Method, A (David Cronenberg 2011)

Descendants, The (Alexander Payne 2011)

Dreileben (Christian Petzold, Dominik Graf, Christoph Hochhäusler 2011) [NYFF Special Events]

Footnote (Joseph Cedar 2011)

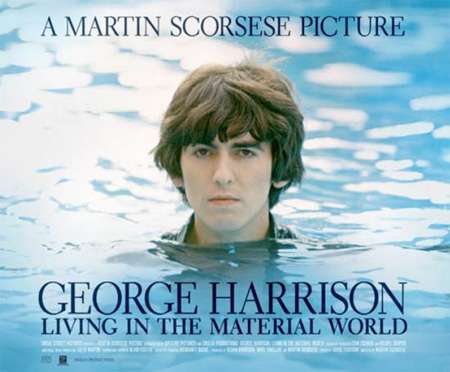

George Harrison: Living in the Material World (Martin Scorsese 2011)

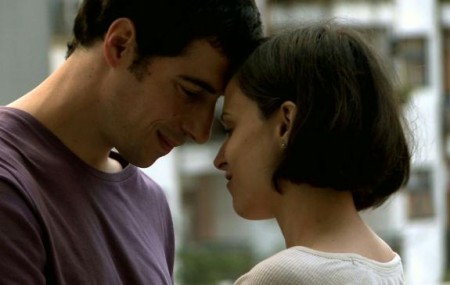

Goodbye, First Love (Mia Hansen-Løve 2011)

Kid with the Bike, The (Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne 2011)

Le Havre (Aki Kaurasmäki 2011)

Loneliest Planet, The (Julia Loktov 2011)

Martha Marcy May Marlene (Sean Durkin 2011)

Melancholia (Lars von Trier 2011)

Miss Bala (Gerardo Naranjo 2011)

My Week with Marilyn (Simon Curtis 2011)

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (Nuri Bilge Ceylan 2011)

Pina (Wim Wenders 2011)

Play (Ruben Östlund 2011)

Policeman (Nadav Lapid 2011)

Separation, A (Asghar Farhadi 2011)

Shame (Steve McQueen 2011)

A Dangerous Method (David Cronenberg 2011)

Skin I Live In, The (Pedro Almodóvar 2011)

Sleeping Sickness, The (Ullrich Köhler 2011)

Student, The (Santiago Mitre 2011)

This Is Not a Film (Jaafar Panahi 2011)

Turin Horse, The (Bela Tárr 2011)

We Can't Go Home Again (Nicholas Ray 1972/2011)

GOODBYE FIRST LOVE, Mia Hansen-Løve

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-14-2023 at 03:51 PM.

-

PRESS SCREENING SCHEDULE Sept. 16-Oct. 14, 2011

Friday September 2, 2011

All screenings and press conferences will take place in the Walter Reade Theater, (165 West 65th Street) unless otherwise noted

Wednesday September 14th Noon-5pm -- credential pick-up

MONDAY SEPT 12-THURSDAY SEPT 15

NO PRESS & INDUSTRY SCREENINGS

FRIDAY SEPT 16

10AM-11:13AM THE WOMAN WITH RED HAIR (73 min) (Nikkatsu Centennial)

11:45AM – 12:50PM INTIMIDATION (65 min) (Nikkatsu Centennial)

1:30PM – 3:30PM MUD AND SOLDIERS (120 min) (Nikkatsu Centennial)

MONDAY SEPT 19

10AM-11:53AM THE LONELIEST PLANET (113 min) *Press conference to follow

1:00PM- 1:48PM YOU ARE NOT I (48 min)

TUESDAY SEPT 20

10AM-11:43AM LE HAVRE (103 min)

12:15PM – 1:48PM WE CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN (93 min)

2:30PM- 4:10PM CORPO CELESTE (100 min)

WEDNESDAY SEPT 21

10AM-1:43PM GEORGE HARRISON: LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD (208 min)

*Intermission for 15 minutes

2:15PM- 3:43PM MUSIC ACCORDING TO TOM JOBIM (88 min)

THURSDAY SEPT 22

10AM-12:15PM MELANCHOLIA (135 min)

1:00PM-2:22PM PATIENCE (82 min)

3:15PM- 4:45PM TAHRIR (90 min)

FRIDAY SEPT 23

DREILEBEN – Part 1, 2 and 3 (88, 89, 90 min)

10AM- 11:29AM PART 1

11:45AM-1:14PM PART 2

1:45PM-3:15PM PART 3

3:45PM-5:10PM ANDREW BIRD: FEVER YEAR (80 min)

MONDAY SEPT 26

10AM-11:26AM TWO YEARS AT SEA (86 min) (Views From the Avant-Garde)

12:00PM – 2:26PM THE TURIN HORSE (146 min)

3:00PM- 4:25PM 4:44 LAST DAY ON EARTH (85 min)

TUESDAY SEPT 27

12:30PM – 2:23PM MISS BALA (113 min)

*Location: Beale Theater, Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (144 West 65th Street)

**Press conference to follow

3:30PM – 4:50PM CARNAGE (80 min)

WEDNESDAY SEPT 28

10AM – 12:03PM A SEPARATION (123 min)

*Press Conference - TENTATIVE

1:15PM- 3:04PM TWENTY CIGARETTES (99 min) (Views From the Avant-Garde)

THURSDAY SEPT 29

10AM-11:50AM THE STUDENT (110 min)

12:30PM- 2:04PM RETALIATION (94 min) (Nikkatsu Centennial)

2:45PM-3:50PM OPENENDED GROUP: UPENDED IN 3D (65 min) (Views From the Avant-Garde)

FRIDAY SEPT 30

10AM-11:31AM SLEEPING SICKNESS (91 min) *Press conference to follow

12:30PM – 3:00PM ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA (150 min)

SATURDAY OCT 1

10AM - 1:43PM GEORGE HARRISON: LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD (208 min)

*Location: Beale Theater, Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (144 West 65th Street)

**Intermission for 15 minutes

***Press conference to follow

MONDAY OCT 3

10AM-11:39AM A DANGEROUS METHOD (99 min)

*Press conference to follow

1:00PM-2:36PM MY WEEK WITH MARILYN (96 min)

TUESDAY OCT 4

10AM-11:15AM THIS IS NOT A FILM (75 min)

12:30PM- 2:11PM MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE (101 min)

WEDNESDAY OCT 5

10AM-11:27AM THE KID WITH A BIKE (87 min)

*Press conference to follow

1:00PM- 2:46PM PARADISE LOST 3: PURGATORY (106 min)

THURSDAY OCT 6

10:00AM-11:39AM SHAME (99 min)

12:30PM – 2:16PM PINA (106 min)

3:00PM-4:40PM POLICEMAN (100 min)

FRIDAY OCT 7

NO SCREENINGS

MONDAY OCT 10

10AM – 11:46AM FOOTNOTE (106 min)

*Location: Gilman Theater, Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center (144 West 65th Street)

**Press conference to follow

TUESDAY OCT 11

12PM -1:57PM THE SKIN I LIVE IN (117 min)

*Press conference to follow

WEDNESDAY OCT 12

10AM-11:35AM CORMAN’S WORLD (95 min)

*Press conference to follow

1:00PM-2:33PM VITO (93 min)

*Press conference to follow

THURSDAY OCT 13

10AM – 11:50AM GOODBYE FIRST LOVE (110 min)

*Press conference - TENTATIVE

FRIDAY OCT 14

10AM-11:40AM THE ARTIST (100 min)

*Press conference to follow

1:00PM- 2:55PM THE DESCENDANTS (115 min)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-05-2014 at 07:08 PM.

-

Julia loktev: The loneliest planet (2011)

JULIA LOKTEV: THE LONELIEST PLANET (2011)

GAEL BARCÍA BERNAL, BIDZINE GUJABIDZE AND HANI FURSTENBERG IN THE LONELIEST PLANET

Two paths diverge in the wild

Hardy and sophisticated offbeat travelers both, Nica (Hani Furstenberg) and Alex (Gael García Bernal), who are to be married in a few months, take a camping trip through the Caucasus with a Georgian mountain guide, Dato (Bidzina Gujabidze). Along the way -- at the film's midpoint -- an incident happens that breaks the cozy mood between them, possibly forever. After Alec makes a split decision that shocks Nica, the two become distant. The title is perhaps a mocking reference to the rough tour guide series, "Lonely Planet." Nica and Alex seem to be intimate and perfectly matched and the trip is gong pretty smoothly, but it all seems to turn into a subtle psychological hell.

This is the sophomore feature of Julia Loktev, who was born in St. Petersburg, Russia, and grew up in the US, studying film at NYU. Her first film was a documentary, Moment of Impact, which focused on the consequences of a near-fatal car accident that her father suffered. Her first fiction feature, Day Night Day Night (shown at Lincoln Center's New Directors/New Films series in 2007), was about a would-be suicide bomber in Times Square. The director has also exhibited art pieces at Tate Modern and P.S.1, and recently received a Guggenheim Fellowship.

Loktev achieves great immediacy in the way she shoots the pair early on bathing, cuddling, and making love in rough surroundings, seemingly in perfect tune with each other. Israel-based, NY-born Furstenburg has luminous skin and flaming red hair; García Bernal has his usual charisma and charm. The pair are almost too clearly cast for each having both playful and melancholy sides: it's almost as if they play only in those two keys. Gujabidze has no particular charm, and his English is a bit rough. But that's the point. He's a real mountaineer and guide, not an actor, and his presence adds to the documentary feel. The other player is the grass-covered, beautiful Khevi region of the Caucasus, which helps mitigate the monotony of an adventure that for the viewer is lacking in much of interest, unless reviewing Spanish verbs, crossing a stream, or doing tricks with a string fascinate you.

The film uses much more limited material and more rudimentary dialogue, but plays with space and time in ways that might suggest the Antonioni of L'Avventura. And in both films events lead up to an event that changes things and that's never fully understood. Whatever the mid-point event in Loneliest Planet means to the characters, they don't discuss it.

Loktev works well in her harsh style. For me, a richer and more nuanced study of the decline of a seemingly perfect relationship between two young people can be found in Maren Ade's Everyone Else, which was part of the 2009 NYFF, and got a limited US theatrical release in 2010. I reviewed it as part of the NYFF. For some, The Loneliest Planet is a maddening snooze-fest, yet another example of how an art film can be like watching paint dry. But for the attentive, adventurous festival viewer, its fresh, raw approach offers stimulation and food for thought.

The Loneliest Planet is a an exhausting, intense watching experience, all the more focused for its vivid immediacy and lack of many plot or dialogue guidelines. It's a taut, effective film, with some pure landscape moments enhanced by Richard Skelton's spare, shimmering music. But Loktev doesn't make as good use as she might of the rearrangement of sensibility. She tends to rely too much toward the end on randomly accumulated material, and the last two sequences are weak. The way Nika and Alex are thrust upon us without backstories, along with the lack of discussion of events, contributes to a mystery that makes this a movie audiences will want to debate. For me the situation suggests a failure of nerve, the kind of thing you might find in a Hemingway short story about a couple game hunting, though his famous "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomer" is almost the reverse of this tale, which is freely adapted from the story, "Expensive Trips Nowhere," by Tom Bissell. In the wild, with a guide, an urban civilized man's courage may be more sorely and starkly tested. Maybe this story could take place anywhere. Loktev has tried to eschew pretty-pretty effects, but the lush, wide-open Georgian landscape is still a bit too distracting. However she is true to the original story: Bissell's fiction generally transpires in Central Asian settings.

The Loneliest Planet was shown at Locarno and Toronto and will be shown at the New York and London festivals. Seen and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. No US distributor at present.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-11-2019 at 07:06 PM.

-

Aki Kaurismäki: Le Havre (2011)

Aki Kaurismäki: Le Havre (2011)

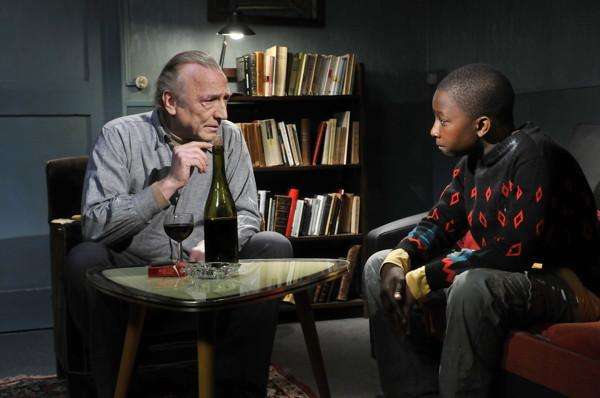

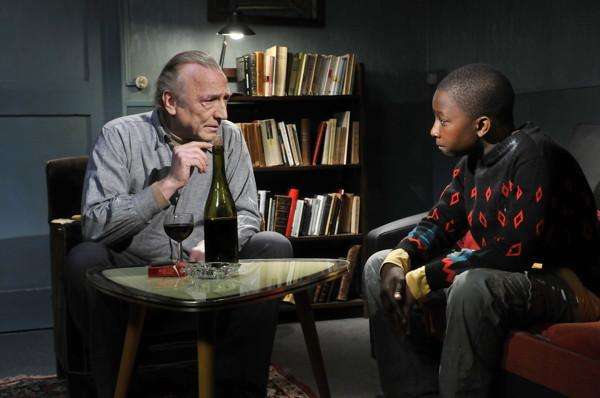

ANDRÉ WILMS AND BLONDIN MIGUEL IN LE HAVRE

Play that old tune again, Aki

Kaurismäki adheres strictly to his signature style here, the usual actors, the deadpan dialogue and sad sack characters, the bright colors, emphasis on blues and greens, direct lighting on actors, sharp images, ironically clear camerawork and editing. But there's something awry: the gloom is missing. The director has said he alwys wanted to have been born earlier to have been active in WWII resistance, and to evoke that, using many references to films of the period like Porte des Brumes and Casablanca and classic directors like Marcel Carné (references in the protagonists' names), Jean-Pierre Melville, Robert Bresson and others. But on its own terms, "Le Havre" is a continual pleasure, seamlessly blending morose and merry n, he filmed a story about a down-at-the heels Frenchman, reduced to shining shoes in the railway station, who becomes a clandestine working-class hero by hiding a young African illegal. For the dyed-in-the-wool Kaurismäki fan there are many little pleasures here but the big pleasure of bathing in a negativism so austere it makes you shiver -- that is totally lacking. Maybe the New York Film Festival jurors picked Le Havre because it's such a homage too French film classics. It's even got an aging Jean-Pierre Léaud in it, as a bad guy, an informer.

Kaurismäki's films always have an out-of-time retro style, which makes the evocation of the French resistance in a modern time setting not a stretch for him. He puts together one of his Finnish regulars, Kati Outinen, as the wife, Arletti, who takes ill but then miraculously recovers, and a French one, Andre Wilms, who was featured in three of his previous films, as the hero, Marcel Marx. Marx and a Vietnamese cohort are getting fewer and fewer shoe shining jobs since everybody is beginning to war sneakers. The camera opens up with a shot of arriving railway passengers' legs, all ending with sneakered feet. In a typically deadpan Kaurismäki sequence, one of Macel's customers gets gunned down after a shoe shine but Marcel only says, "well, at least I got paid first." Kafkaesque menace abounds here (with Kafka even red from to the ailing Arletti), but the horror is distinctly muted.

Hence when a container is found that's been left sitting for a week or two, and it turns out to have a group of African stowaways in it, they are all sitting around in the box, perfectly well, still, nicely lighted. One of them is a young boy, Idrissa (Blondin Miguel), who bounds out of the box and runs away. Marcel is destined to find him and save him and see that he gests to go to London where the waylaid container box was headed and where he has family. After finding him hiding in the water and bringing him food, Marcel protects Idriss at his house. His wife has gone to the hospital due to an undefined but possibly fatal illness (she never looks sick, nor will she allow the old, burt-out looking doctor to tell Marcel that it's serious). Idriss stays hidden without any problems, shining shoes or washing dishes when needed. He also speaks perfect French.

Marcel gets help from his shopkeeper neighbors, who forgive his debts more willingly now in complicity against the mean police. But nothing must help it, Marcel needs to raise 3,000 euros to pay a man to take Idriss to London illegally. To raise this sum he gives a charity concert. This droll event features an aging rock musican-singer with a puffy head of white hair called Little Bob (Roberto Piazza).

It's a pleasure -- chiefly visual, but otherwise cinematic -- to watch Kaurismäki at work. His bright colored yet restrained style, and his use of cameraman Timo Salminen and editor Timo Linnasalo show a look and rhythm that are elegant and consistent. Everything he includes in a film becomes Kaurismäki. And there are those that will like the director even more with an ubeat, updated theme. However, it's really not the same without the pessimism. Without it, the drollness loses its edge. Hard to see the point, really, or at least the necessity of showing this in as selective a film festival as New York.

Le Havre was included at Cannes and Toronto as well as the NYFF (and other festivals); it will be released theatrically in France, Sweden, and Slovenia in December 2011. Screened and reviewed as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. Janus Films has acquired tis film for US release October 21, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:35 PM.

-

Nicholas Ray: We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011)

Nicholas Ray: We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011)

OVERLAPPING IMAGES FROM WE CAN'T GO HOME AGAIN

Shattered mirrors

It's for the experts, notably among them Jonathan Rosenbaum, to describe the relationship between this film by Nicholas Ray and his State U. Biningham students, and his wife, and its other versions and another film or other films that relate to it or grow out of it. The consensus is that the orginal We Can't Go Home Again was "finished" in 1972, and shown at the Cannes Festival in 1973. But it wasn't satisfactory, and it wasn't shown under satisfactory conditions, being screened at the end of the festival when everyone was too tired to take it in. There have been various versions since. This current new version, carried out under the supervision of Ray's widow (and fourth wife) Susan and completed this year under the auspices of the Nicholas Ray Foundation, The EYE Institute of the Netherlands, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive, adds new voiceover material provided by Ray himself replacing a student's voiceover, and there are other improrovements, notably a ditigalizing of the images.

We Can't Go Home Again is by and about NIcholas Ray and his film students in New York State at that time in the early Seventies, and all the things that were going on in their minds and in their lives at that moment, including their love affairs; the state of mind and professorial voice of Ray over ten years after stopping to make movies in Hollywood; the Vietnam War; the Seige of Chicago; the dynamics of a film class focused on making a film; and so forth.

To do justice to all this complexity, Ray and his collaborators use an interesting, alternately separate and overlapping, multiple screen technique. It's not at all a aslick, symmetrical split-image setup, but something more complex, sui generis, and expressive. The whole screen sometimes is used as a framework showing the Binghamton campus, with the various films the students shot set, small, a little to one side, within that big frame. Sometimes there are several or multiple frames in the big frame. Sometimes the film takes over the whole screen like a conventional motion picture. And the frames within the frame are of different formats. There are also different sound tracks that overlap while different frames are unreeling on parts of the big screen.

I liked this. It seemed a good way of capturing the effect of a chaotic collaborative effort. Ray himself dominates, along with several of the students, such as Leslie and Richard, a twenty-something couple who are both students in Ray's class. Ray is always puffing on a cigarette, usually wearing a black eye patch (though sometimes not, and once he's asked why and he says, in effect, that it just gets too damp and icky sometimes), and he's also seen wearing a red jacket.

Ray is wearing the red jacket, which Jonathan Rosenbaum says "inevitably recalls James Dean’s in Rebel [without a Cause]," in a long sequence out by a barn, where he goes aloft with a rope, aiming to hang himself, and in the course of botching the job, uttering the immortal line, ”I made 10 goddam Westerns and I can’t even tie a noose!" Ray doesn't die. He lived on to die of lung cancer in New York City in 1979.

It is essential to We Can't Go Home Again that it should be a mess and that it should have no definitive version. It's a monument to Ray's final years and to the sprirt of the early-to-mid Seventies. Ray had drug and alcohol problems; he later joined AA. He used drugs with his Binghamton students (it was the Seventies). The style of We Can't Go Home Again is very Seventies and very druggy. The film is also a remarkable expression of an intimate collaboration -- no doubt in a sense much too intimate -- between an arts teacher and his passionate young students, who challenge him in this film but also love him.

In his August 2011 discussion of this film on his blog, Jonathan Rosenbaum sums up We Can't Go Home Again using a comparison drawn from what for me is Ray's most haunting, and drug-trance-like, Hollywood film: "The multiple images that were combined via rear projection photography are often extraordinary, and the total effect of this graphic, innovative, agony-ridden document seems to be somewhere between the Guernica of disaffected America that it clearly aims for and the shattered bathroom mirror in which James Mason examines his fragmented features and identity in Bigger Than Life, his most disturbing Hollywood film. The dialectic between cracked self and atomized other is a central theme throughout."

This restored version of Nicholas Ray's collaborative We Can't Go Home Again (1972/2011) was premiered at Venice and also included as a sidebar item of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center in 2011. It was screened at Lincoln Center for this review, with a Q&A including Susan Ray.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:42 PM.

-

Alice Rohrwacher: Corpo Celeste (2011)

Alice Rohrwacher: Corpo Celeste (2011)

YLE VIANELLO AND ANITA CAPRIOLI IN CORPO CELESTE

Coming of age in Calabria

Italian director Alice Rohrwacher's debut feature is obviously not going to be just a a quiet, understated study of a pre-teen girl's first experiences of religion, a new environment, and sex, though of course those are heady topics anyway. That's clear from the opening scene, a hand-held depiction (shot by excellent French cinematographer Hélène Louvart) of a realistically kitsch outdoor saint ceremony, complete with unappealing priest and recalcitrant speaker system, that is already something out of a latter-day Fellini. And where is all this happening? In a studiously rendered, newly rebuilt Reggio Calabria, which looks like a garbage dump and a highway, and whose newer church interiors look like cineplexes.

But tendentiousness is avoided by having everything that will follow filtered through the lens of almost-13-year-old Marta ( a limpid and picaresque Yle Vianello), the protagonist, who has recently been brought back to Calabria with her childish young mother Rita (Anita Caprioli) -- uisually exhausted from working at an industrial bakery -- and her annoyingly bossy and condescending 18-year-old sister after they'e all come back from ten apparently fruitless years in Switserland. It's Marta who get sent to a confirmation class to meet other kids and, I suppose, get with the local scene, in which a giddy pop, plastic version of catholicism is a central feature. "Seeing the Spirit is like wearing really cool sunglasses," is one of the slogans the kids are sold. Marta doesn't even know how to do the dign of the cross. But she's a quiet and perceptive child.

Rohrwacher, whose older sister Alba is a famous Italian actress, is content with crowded vérité sequences of relatives and neighbors and the jaw-dropping confirmation classes for a while. Pasquilina Scuncia is strong in these scenes as Santa, the unctious, goading teacher who's obsessed with the priest, whom she's either having an affair with, or would like to. But then the writer/director embarks on a lengthy fugal passage that touches some profound and shocking chords. Marta runs far out of town pursuing a man on a vespa who's been sent to kill some neworn kittens found in the churchand dump them in the river. So much for Christian kindness coming out of this church, which is big and ugly and has a futuristic neon cross of the altar that looks vaguely corporate and commercial.

Woven in and out of the whole film is the stunningly unappealing local priest, Don Mario, played by Salvatore Cantalupo, who in Gamorrah was the tailor who stupidly thought he could outwit organized crime. Don Mario is similarly doomed, and venial. He thinks he can force signatures from obedient parishioners to help get himself promoted to a more important church that might step him up to bishop. There is not one ounce of authentic religiosity in the quietly creepy Don Mario. Somehow he winds up finding Marta on her useless kitten-saving odyssey, and taking her along in the SUV when he goes to his village church to collect a large wooden crucifix, which is meant to be a central part of the confirmation ceremony that is to take place any minute. The crucifix won't make it. But while the priest isn't looking Marta gets to fondle the carved muscles of the wooden Jesus, her sexual and religious explorations momentarily dovetailing.

In the little church, grabbing the carved Jesis on the cross, Mario clashes with an older priest who might be his own father. Smoking a cigarette in the hurch the older man gives Marta a lesson about another Christ, not simple and good but misunderstood and angry. When Marta tells Don Mario about this Christ, it makes him run off the road and the wooden Jesus falls down into the river.

Outlines this way, these events may seem overly pointed, but Rohrwacher makes them work, partly by cross-cutting with preparations for the confirmation, which is supposed to take place now, and partly because everything is beautifully filmed. Don Mario is very late because he has stopped to eat a good meal in a seafood restaurant, while Marta stands around waiting. At some point in this extraordinary afternoon Marta has her first period. Maybe Rohrbacher loads her dice pretty heavily, but her use of the local trappings of modern, kitsch, uglified Calabria, her staging of birthdays and confirmation classes and creepy encounters with various church officials, not to mention the trip to the outlying town and the "authentic" older priest, as staged with great energy and assurance, Vianello, Scuncia and Cantalupo are all pretty memorable, and one has the feeling that Rohrbacher really cares about this stuff. The way things are lately, an Italian film this good is cause for celebration. The place and the child are quite memorable.

Corpo Celeste/Celestial Body debuted in the Directors' Fortnight at Cannes this year and is part of the main slate of the New York Film Festival, where it was screened for this reveiw. Film Movement has bought Corpo Celeste for North American release.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:46 PM.

-

Martin Scorsese: George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011)

MARTIN SCORSESE: GEORGE HARRISON: LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD (2011)

Double biopic of the Beatles' seeker-guitarist

This HBO miniseries by Scorsese, which adds to a musical portfolio including a Rolling Stones concert (Shine a Light) and a Bob Dylan biography (No Direction Home) focuses on the other Beatle who isn't around any more, and perhaps the must mysterious and different of the four as well as ostensibly the one who most deeply sought to explore life's meaning. George is the one who was on a spiritual quest, and it led him to playing the sitar and meditation, explorations that changed the band's style and its members' behavior. Scorsese makes very good documentaries of the archival, illustrative, rather than investigative kind. It's an interesting paradox that a man in the middle of a media circus like George Harrison of the Beatles would go on serious search of inner peace and deeper understanding. Harrison explains this in a vintage TV interview. He says they found great material success early in life and so found out early that it was not the answer.

The Beatles must be among the most documented entertainers in history. There's no shortage of material, including plenty of interview footage with Harrison and people interviewed recently about him, like Ringo Starr, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, later Eric Idle. But is this the way to get to the core of a life? Is this the way to get an insight into some of the most popular of all pop music? Scorsese provides a glossy survey, with great sound when the songs come (though they're not always allowed to run long enough) , and with plenty of sighs and gasps and chuckles along the way. And we have a good organizer: David Tedeschi, who edited Scorsese's superb Dylan bio, also did the editing here.

The film begins with Harrison's youth, then the Beatles' early days from Hamburg to the meteoric media rise, much of it narrated via letters home from George, writing to his mother. As Peter DeBruge of Variety points out, Scorsese assumes an audience already "up to speed" on the Beatles story and therefore does not bother to introduce some of the speakers till several hours in. Among the "many small details omitted along the way" is Stuart Sutcliffe, the band's lost bassist, not even fully named, and nothing much is explained about the Beatles' manager Brian Epstein till the moment of his death in his early thirties (also unexplained). Black and white still photographs are often beautiful, finely rendered, and introduced at just the right moment, but not provided with much context. Though this documentary (which runs to over three and a half hours) provides a wealth of material, it seems more celebratory than informative.

The key trajectory, of course, is Harrison's shift to eastern music and thought. There's more than one hint that LSD opened portals of perception that Harrison knew needed to be kept open by natural means. It's clear that Harrison became not just a pupil but a friend of Ravi Shankar. This orientalism led the Beatles to go from being the adorable pop band for screaming teenage girls through the Sergeant Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band to a Sixties and Seventies cultural icon worthy of endless interpretation and academic scrutiny.

Somehow George Harrison went from coolness and inner peace to far too many drugs and a burnt-out voice. The film doesn't offer anybody who can explain this. Could it be something it does describe, the fact that Eric Clapton went off with George Harrison's wife? The hard parts come in Part II. This is when 1970 comes, the Sixties ends, the group breaks up (nothing about the rift caused by Yoko Ono). Harrison makes his solo albums, gives the Bangladesh concert, gets involved with Monty Python and funds their Life of Brian, starts his own film production company, and moves to the giant Victorian mansion, Friar Park: the film turns personal, and ends with Harrison's stabbing and subsequent death from cancer.

After Lennon's assassination the film infomrs us how Harrison spent a lot of time preparing for death and in doing so managed to be in a state of relative wisdom and peace and positivity when the end came.

DeBruge argues that of all the Beatles Harrison is the most worthy of a detailed portrait because of the way he changed and sought answers to the deepest questions about life's meaning. But that is debatable. McCartney is the musical genius of the group. I personally would like to learn more about the music and how they made it, topics that seem secondary here, except for some good interviews with producers, including Phil Spector. And Lennon is still arguably the most charismatic and intellectually complex personality and, of course, he has been documented well already for that reason. I don't think this ranks with Scorsese's Bob Dylan biography; but it's not like you'd want to miss this if you are a Sixties or pop music fan. There is a handsome coffee table book to accompany it.

Screened for this review at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, in which it is a main slate selection. Also opens in the UK on October 4, 2011. The two-part film, 208 min total. US HBO TV premiere October 5, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-09-2011 at 05:52 PM.

-

Lars von Trier: Melancholia (2011)

LARS VON TRIER: MELANCHOLIA (2011)

Alexander Skarsgård and Kirsten Dunst in Melancholia

The party's over now

The mid-May screening of Lars Von Trier's Melancholia at Cannes a couple of days after Terrence Malick's Tree of Life inspired many comparisons by critics. Mike D'Angelo of Onion AV Club even went so far as to imagine it was as if Von Trier had seen Tree of Life and made a feature film in 48 hours as a "rebuttal" to it. Both films have a cosmic sweep and both focus up close on troubled families. Von Trier's beautiful prologue, with its figures floating in super-slow-motion in a dramatic dark landscape to the sound of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, as well as the much larger planet coming to splinter the earthn the second half, somehow together parallel Malick's images of orbs and galaxies floating through space balanced against his elder son brooding over and remembering his youth. If you play one film against the other the contrast in mood is as stark as the difference between Jessica Chastain's voiceovers about grace and affirmation in Tree of Life and Kirstun Dunst's declarations in Melancholia that the earth is "evil" and if obliterated will not be missed. Obviously Melancholia isn't a happy film. Dunst's Justine "knows things" and is sure there is no companionship or redemption awaiting us out in space (the recent sci-fi indie Another Earth notwithstanding). Tree of Life has doubts and sorrows too. One of its chief playbooks is the Book of Job. But it's also full of a sense of imminence and awe.

These are both grandly ambitious, strong, beautiful films, among the year's best. They also differ hugely, apart from mood, in their ways of looking at time. Tree of Life gazes continually backward. Melancholia stares numbly upon the present, with only occasional quick terrifying glimpses into the future. As we wait and wait upon a bride whose growing depression slows her to a halt, the film delivers a palpable sense of drawn-out real-time present. As it ends, the future becomes now, and never.

Such comparisons aside, emotionally and artistically Melancholia initially has much in common with Von Trier's previous film Antichrist in having emerged from the same period of profound depression the director was going through. But Melancholia goes to fewer extremes as provocation and departs less from "reality." Melancholia has provocative moments, but its horrors, however posh the staging, are closer to the everyday experiences of anger, selfishness, and recrimination. The new film has an obvious direct kinship with with Thomas Vinterberg's 1998 The Celebration, "the first dogme film." The Celebration focuses, as does the first half of Melancholia, on a large and festive gathering of a family whose leader is a titan of business. Vinterberg's focus is a birthday, Von Trier's an expensively staged wedding party: both lead to public accusations and verbal fighting and a general degeneration of what was to be a festive event. Moreover though Von Trier's staging is infinitely more grand (and, considering the film as a whole, more beautiful), except for during the opening slo-mo sequence he uses the same constantly swinging, jittery dogme-style camerawork throughout Melancholia, as if to link his grandiose, epic present style with his more Brechtian dogme roots. (He has said that the cinematography in Antichrist came out to be more beautiful than he originally intended.)

Melancholia is operatic in its production even to its theme music, and feels close to something like Patrice Chéreau's last great film success, the 2005 Gabrielle -- Chéreau being literally one of the great designers of European opera productions. At the same time the epic emotions have a strong physicality through the closely filmed stars, John Hurt as the frivolous but sympathetic dad, Charlotte Rampling as the cruel, blunt-spoken mother, Kiefer Sutherland as the materialistic brother-in-law, above all Charlotte Gainsbourg as Claire, Justine's "normal" sister. Gainsbourg has become a Von Trier regular. Her casting here doesn't seem quite right at first, but the point may be to make the sisters reflective opposites who are partly interchangeable. Dunst, the depressive, seems superficially down-to-earth and strong, and becomes the solid one as the apocalypse draws near, while Gainsbourg, the more positive and sensible of the two sisters, is wispy and gray and has an air of melancholy about her, of the sad, sullen striver, and as chaos approaches she wilts. The contrasts are really not quite that easy, either, but roles do subtly reverse as doom approaches in the film's second half. To play Michael, the groom, Von Trier has chosen the tall heartthrob (and TV vampire) Alexander Skarsgård, fresh, blooming, and cheerful. Udo Kier, in fine form, is a semi-comic wedding planner who becomes so furious with Justine for ruining the event, he refuses to look at her and averts his gaze or covers his eyes in her presence. Wedding planners the world over can doubtless relate. Despite its lugubrious pace the first half of Melancholia is full of little comic touches that signal that this is somehow one of Von Trier's least harsh and provocative films.

The first, "Justine," half of the film shows the bride gradually more and more obviously alienated from her sister, her new husband, her boss and her parents. At some points her negativity seems excessively schematic and Brechtian, but Kirsten Dunst, who won the Best Actress award at Cannes for this performance, is convincing and natural and awakens sympathy -- as well as impatience. Justine gradually drifts away from the party and becomes increasingly sad and desperate during the night. Many of the guests and even the sisters' father (John Hurt), whom she begs to stay, go home, the groom himself departing with astonishingly little protest -- perhaps so well aware of Justine's emotional issues he half expected this debacle all along.

The second, "Claire," half stays at the castle where the party took place, also the home of Claire, her husband John (Sutherland) and their little boy, Leo (Cameron Spurr). The mood is more intimate but attention now shifts from individuals to the firmament. The mysterious orb in the sky is now revealed to be a planet approaching the earth. John, perhaps to maintain family order, holds to the declaration of some scientists that the planet will pass by without trouble. But Claire finds an online counter-story that describes the two planets' approach as a "Dance of Death." She is printing it out when the electricity dies and everything shuts down. The rest becomes a quiet, internalized allegory of the end of the world that is haunting and beautiful. Wonderful use is made of horses in the stable that Claire and Justine go out riding on (till Claire won't or can't), become violently troubled as the firmament is disturbed, and then grow ominously calm.

Melancholia gives one much to chew on, and chewing is possible because the material is quiet and Bergmanesque, lacking either the high-handed indictments of America, the sexual extremes, or any of the usual Von Trier provocations, but richly displaying the director's gifts as a maker of complicated dream worlds with telling parallels to our own experience. The final sequences have something in common with that most depressing of all movies, Michael Haneke's The Seventh Continent, but the beauty and grandeur give one a far different sequence. Besides, these people, though the depressive, deeply pessimistic Justine may embrace it most readily, do not choose extinction as does Haneke's little suicidal Austrian family: they merely prepare and wait for it. Von Trier's art house strategy is so cunning that his world ends neither with a bang nor a whimper. The final shot simply explodes in our own heads. The director has given himself a hard act to follow this time. His blend of science fiction, social commentary and psychological study, presented via superb cast and striking mise-en-scène, adds up to high cinematic pleasure, despite the dark matter.

Melancholia debuted at Cannes May 18, 2011. It has been included in other festivals, including the Toronto and New York. Following VOD Oct. 7, limited US release by Magnolia Pictures begins November 11. Included in the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center and screened there for this review.

*A web page: "Malick vs. Von Trier@Cannes: http://blog.uvm.edu/aivakhiv/2011/05...-trier-cannes/

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-30-2014 at 11:03 PM.

-

Béla Tarr: The Turin Horse (2011)

BÉLA TARR: THE TURIN HORSE

ERIKA BOK IN THE TURIN HORSE

Imagination dead imagine

The Hungarian director Béla Tarr is not for everyone. His style is distinctive. HIs venue is the film festival. He works in black and white, and at length. Great length. The subject is often people in remote places oppressed by dire weather. One of his masterpieces is Satantango (1994), about a village whose inhabitants are squabbling over cash: it's seven and a half hours. Werckmeister Harmonies (2000) concerns a town oppressed by frost, and villagers gathering outside a great exhibit of a whale carcass. Two and a half hours. The Turin Horse, which he declares will be his last film, also two and a half hours, concerns a bearded man, his dreary granddaughter, and a flea-bitten workhorse. They are out in the middle of nowhere, their primitive house and stable surrounded by howling winds. A dust storm rages, with a background of grinding strings swirling over a repeated cluster of notes.

The pretext for The Turin Horse is an apocryphal story of Nietzsche in 1889, when he saw a cabman abusing his horse and intervened, throwing his arms around the pathetic steed. We know what happened to Nietzsche, but not what happened to the horse, says the film's intro. Tarr endeavors to correct that with six days in the lives of the cabman Ohlsdorfer (Janos Derzsi), his granddaughter (Erika Bok), and the poor beast. Tarr tells a tale of daily rituals, suffering, darkness, and attrition. Gypsies raid the well, and later it has gone dry. Deprived of water, Ohsdorfer and granddaughter pack up essentials and leave, pulling a cart. The horse, which has lately refused to move or eat, accompanies them. But a day later they return and unpack everything. Eventually the winds stop, but the lamps won't light, and the embers die out: no more fire or light. And still no water. Only liquor.

Ohsdorfer and the woman are like Hamm and Clov in Samuel Beckett's Endgame without the wit and glorious language and cosmic setting. This pair hardly talk, and when they do, they speak in grunts and expletives. The granddaughter helps Ohsdorfer dress and undress, gets water (when there is any), tends to the horse (perhaps), boils potatoes. One big potato each is their sole meal, eaten off a crude dish without utensils. When they have come back from their attempt to escape, Ohsdorfer sits and looks out the window. His granddaughter eventually stops eating. The horse looks bad, but is still alive.

The Turin Horse is an exercise in style and mood. It tells us nothing, but its slow movement and dark look stays with us after the film is over. None of this would work without the grinding cellos and other string instruments underlining everything with a sense of grim, noble determination.

Gus Van Sant has cited Béla Tarr as a "huge influence" on his later, more arthouse work, beginning with the slow-moving and stark Gerry, which concerns two lost young men in a desert wandering about hopelessly. Tarr takes us back to the primitive roots of film. But is he a good influence or a bad one? The Turin Horse is one of Tarr's grimmest, most minimal films. It seems to illustrate Samuel Johnson's motto uttered in Rasselas: "Human life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured, and little to be enjoyed." Here, we don't get the benefit of Beckett's cosmic jokes, not in so many poetic words, anyway. Of course The Turin Horse, which also has a visitor whose monologue provides an indictment of the villagers and perhaps all humankind, but one that Ohsdorfer dismisses as sheer bunk, is full of symbols one can while away many delightful hours in interpreting.

Tarr is a metaphysical visionary whose viewpoint is very distinctive. The technical aspects of his films are impeccable. This film was shot in handsome black and white by cinematographer Fred Keleman (who also did The Man From London, NYFF 2007), distinctively scored by Mihály Víg and co-written by longtime Tarr collaborator László Krasznahorkai. Each "day" consists of a very few long takes, which are enlivened by Tarr's technique of following his characters around the convincingly weathered hovel (designed by Sandor Kallay) with a Steadicam.

The Man from Turin has been shown at major festivals, including Berlin (where it won the Silver Bear), Hong Kong,Moscow, and Toronto, and the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. The Cinema Guild acquired U.S. distribution rights and plans to release the film theatrically this winter.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2011 at 09:31 PM.

-

Abel Ferrara: 4:44 Last Day on Earth (2011)

ABEL FERRARA: 4:44 LAST DAY ON EARTH (2011)

WILLEM DAFOE AND SHANYN LEIGHT IN 4:44 LAST DAY ON EARTH

Gore was right: let's talk on Skype

It's an ecodisaster: Gore was right, talking to Charlie Rose. So was the Dalai Lama. So were various other people seen on TV randomly in Willem Dafoe's loft apartment in New York as he hangs out with his girlfriend and talks to various people on Skype and in person, skipping over fire escapes to peek in on some friends whom he hasn't seen for some time.

The girlfriend paints bad Jackson Pollack knockoffs as they wait for the end. A TV anchorman excuses himself to go home to be with his family because, you see, this is the last day on earth. It's all going to explode, or something, later.

When you know the planet and all living things are finished, what do you do? Probably not spend your time with Cisco (Dafoe), a nervous worrier with nothing particularly interesting to say, or his young girlfriend Skye (Shanyn Leigh, the director's girlfriend), an insecure lass in pink silk pajamas (she later changes to a small dark dress) with artistic pretensions and jealous feelings toward Cisco's ex. One of the difficulties with dramatizing their efforts to make things right before the end is that we know little about them and less about their friends and family. For example, when Cisco arrives at his friends' apartment via fire escape and spends a little itme talking to them, we never quite learn who they are. There's a discussion of whether a man long in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction would want to go back to using now, since it's all over, so to speak. He doesn't. He wants to see the big bang bright and clear, not numbed by substances. Cisco isn't so sure. He thinks if there was ever a time to get high, it's now. This is a discussion that anyone in recovery would be familiar with.

Most of the screen time is spent at Cisco's loft studio apartment on the lower east side, where very little is happening, except for the mutimedia display provided by Ferrara's setup of computer, big screen TV, iPad, and other gadgetry. Cisco and Skye take refuge in sex for a while, which involved an up close squence of him caressing her naked arse and thighs that is very uncomfortable to watch. Again, the Skype farewells, when Cisco's to his ex-wife causes Skye to scream and grab Cisco and the laptop. Rarely have we seen such a dramatic Skype exchange. Come to think of it rarely have we seen so many Skype conversations in a film. The best Skype moment is provided by a Chinese food delivery boy who asks to Skype his family in China. We don't know what they're saying -- no subtitles are provided -- but when he kisses the screen, closes the laptop, and kisses it, then walks out bowing after his hosts have hugged him and given him money, it's clumsy, but also quite touching. Skye is prompted to appeal to her mother, also on Skype. In this role Anita Pallenberg briefly provides some European maturity and good taste.

Ferrara hits his technology/media theme hard, but not to great benefit.

This film looks pathetic when one has recently watched Part II of Von Trier's Melancholia, which achieves grandeur and solemnity with a similar theme. Ferrara's film suffers not so much from a lack of budget as from a lack of vision, lack of explanation for the apocalypse, lack of structure for the story, lack of plot and lack of interesting dialogue. Ferrara delivers a positive message about reuniting with loved ones at the end, but the context never gives it an emotional punch. There's a disaster here, but it's not the plot, it's the whole movie. 4:44 is as unfortunate as the selective New York Film Festival's main slate choices ever get.

Ferrara has his devoted fans, some of whom seem to be members of the New York Film Festival selection jury. His Go Go Tales, not appreciably better than this, was part of the 2007 NYFF. Ferrara at his best, as in King of New York (1990, with Christopher Walken), Bad Lieutenant (1992, with a fearless Harvey Keitel), and The Funeral (1996, again with Waken), is always chaotic, but the chaos in those films contains solid meat you don't find here. Fans will be glad that after a long break the director returns to his native NYC, but the film doesn't open up enough to make good use of the location. This time the chaos just seems like diffuseness, and even certainty of imminent death fails to focus the characters' thoughts sufficiently.

4:44 was shown at Venice and, as mentioned, the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review. It will be released commercially by IFC Films.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-27-2011 at 07:45 PM.

-

Gerardo Naranjo: Miss Bala (2011)

GERARDO NARANJO: MISS BALA (2011)

STEPHANIE SIGMAN IN MISS BALA

Bird's eye view

Gerardo Naranjo's third film, Miss Bala, is all about point of view. He chooses to tell a tale of Mexican drug cartels and cop-gang war crabwise, from the angle of an innocent young woman whose only desire is to be a contestant in a local beauty contest. She is the pretty, sad-eyed Laura Guerrero (Stephanie Sigman), a 23-year-old from Tijuana who goes out one morning with her girlfriend Suzu to enter the competition for the title of "Miss Baja." Bala, bullet, is an ironic twist on that title. The gangsters who come in contact with her, particularly Lino Valdez (Noe Hernandez), a gang boss who survives a local police purge, force Laura to help them as a driver. He gives her her own gang name, "Carmelita."

Various virtuoso set pieces, elaborately staged for a largely static camera in very long takes that emphasize Laura's powerlessness over events, unroll while she is an unwilling witness, and sometimes a direct participant. To begin with, she and Suzu go from the beauty contest signup to a little party at a place called the Millennium Club where there are a bunch of men in uniforms dancing. They turn out to be American DEA agents and the party turns into a massacre -- the first of the set pieces, which will grow in violence and complexity: another one is a bullet-drenched police-gangster shootout in plain daylight, and the final one is another shootout when Laura is in a general's bedroom.

At the Millennium Club, Laura hides and survives but Suzu disappears. Laura comes around the next morning asking a cop to help her find Suzu, and he says he'll take her to the station to tell shat she saw. But instead she is delivered into the hands of Lino, and her unwilling collaboration begins. In return for it, Lino sees that she is reinstated as a contestant in the Miss Baja pageant, so her participation in this most frivolous aspect of Latin American life continues to be woven in and out of her involvement in revenge killings, acting as a decoy for an assassination, and helping to carry thousands of dollars and boxes of ammunition and weapons across the Mexico-US border in dealings with the US syndicate, which they refer to as "La Vaca." The gang Lino is in is called Estella. Lino apparently arranges to have Laura win the "Miss Baja" title -- since all is from her viewpoint, we never know the whys and wherefores -- which helps him, because it guarantees that Laura can gain the attention of the general Lino wants to killl and get her into his bedroom.

In nothing does Laura have a free hand. She is pushed here and there, and Miss Bala becomes a sort of picaresque tale whose heroine is neither quite innocent nor quite guilty. In this her role parallels that of the majority of ordinary Mexican citizens, who are drawn into the widespread criminality and violence willy-nilly. They may not know what's going on in their own backyards till it bites them in the face. And we have to strain to follow the elaborate gang war going on around Laura, because she doesn't understand it. She keeps escaping and getting caught again: Estella is omnipresent and omniscient.

This film has a strange kind of mood. It's an adventure, but there's something -- doubtless intentionally -- numbing and deeply sad as well as compelling about its thrills because of the way the narrative shows violence being absorbed into all of Mexican life. Again the carefully choreographed sequences done in a few long Steadicam shots contribute, providing a sense of detachment from the event, while also underlining that it has a life that is independent but also enveloping. The effect isn't flashy: it conveys a sense of powerlessness, not elation. At key moments the wide aspect ratio shot finds Laura's face in its dead center staring forward, sometimes numbly, sometimes weeping. (The film is shot in anamorphic 35mm.) These are the defining shots of the film, which still does read as an action film, but with one with a distinctive personal style that includes many moments of stillness, and thus is far from the precipitous loud action of the conventional thriller. The use of music is very restrained, but Pablo Lach's sound design is very effective in maintaining different a degree of menace even at quiet moments. The Hungarian cinematographer Matyas Erdely, a new collaborator for the director, contributes the look along with Naranjo's choreography of scenes.

Miss Bala delivers on the growing promise and complexity of his previous two films, Drama/Mex (LFF 2006) and I'm Gonna Explode (NYFF 2008). (There was a LA-shot first feature, the 2004 Malachance, which I haven't seen.) Miss Bala, which has already been picked up by Twentieth Century Fox after showings at Cannes and at Toronto and chosen by Mexico as its entry in this year's Oscar competition, is being compared to Heat and Scarface and called a ticket to Hollywood, should Naranjo want to migrate. (But what makes this film so good is everything that is non-Hollywood about it.) Peter Debruge of Variety (who noted the Hollywood potential) calls Miss Bala a "blistering firecracker." Diego Luna, speaking at the film's Mexico City premiere (and an executive producer with his pal Gael García Bernal), noted this film's relevance to its place and time and said "we are in the midst of a war that we wanted to believe was not affecting us." Naranjo tackles the very violent country that Mexico has become from a fresh angle and with a distinctive, quiet virtuosity.

As Mike D'Angelo noted with surprise in his Cannes coverage, the film was shown there out of competition. It was also shown at Toronto, and included in the New York Film Festival, where it was screened for this review It is scheduled for limited US release October 14, 2011 (Twentieth Century Fox), UK release October 28, and in France February 1, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-07-2011 at 10:41 PM.

-

Roman Polanski: Carnage (2011)

ROMAN POLANSKI: CARNAGE (2011)

JOHN C. REILLY, JODIE FOSTER, CHRISTOPH WALTZ AND KATE WINSLET IN CARNAGE

Verbal blows in Brooklyn

In a way Polanski gets to do his Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf in Carnage, as Mike Nichols got to do with Edward Albee's original play when he filmed it in 1966 -- though he hasn't got Liz Taylor and Richard Burton and this is not as rich and resonant a play. Here the ironies are a little too easy; they do not go deep enough. Carnage, the title trimmed down from the original The God of Carnage, which the director rewrote for the screen in collaboration with the French-born playwright, Yasmina Reza, is a drama in which two couples start out ever-so-polite and wind up Neanderthal. It's been described as a one-joke play. However, Polanski's direction neatly brings out the nuances of that joke and brightly tunes up the crescendo of blatant hostility between and among couples that comes in the last quarter of the 80-minute interaction. The director has done something like this before, with Death and the Maiden (1994), also from a play, by Ariel Dorfman. Which was the year of Art, Reza's previous London and New York hit (both plays produced from English translations by Christopher Hampton). This time Polanski made use of a more literal translation by Michael Katims.

Is this as good as Maiden? Maybe. As powerful as Virginia Woolf? Hardly. Is making a play as restricted as this to living room, kitchen and bath into a movie necessary? Debatable. (Polanski worked deftly in small spaces with The Tenant and Repulsion, but that was different, and more cinematic.) But one can argue that the activity is comparable to recording classical music instead of simply performing it live. There is a chance to get it absolutely right. There is the loss of the magic of stage and audience, but there is a precision, which fits Polanski's style very well. Given this kind of format, he delivers. And this time his technical staff conspire to make the action appear smooth and seamless in a way it cannot on stage.

This, like Virginia Woolf, is a four-hander, cast for the film with Christof Waltz and Kate Winslet as Kate and Allen Cowen, a corporate lawyer and an investment banker, and John C. Reilly and Jodie Foster as Michael and Penelope Longstreet, a hardware salesman and a writer and bookstore employee. Great casting. Not that they're necessarily better than James Gandolfini, Marcia Gay Harden, Jeff Daniels and Hope Davis, the quartet who took the roles on the stage in America. Reilly is goofy, where Gandolfini is menacing and Neanderthal from the start. Waltz is smooth and understated, where Daniels was annoying from the start. Foster is not just prissy but muscular. Winslet is a bit like that too. I found their voices too similar; perhaps Wislet, putting on an American accent, was subconsciously imitating Foster. Waltz stands out again as an actor of extraordinary versatility (thanks, Quentin); Foster is strong and amusing; Winslet is a slow burner; and Reilly neatly creeps up on you. Fine ensemble work here, no doubt about it.

The film begins with a long shot showing the violent incident between the two 11-year-old boys in Brooklyn Bridge Park that is not seen in the play; the interior action was all shot in Paris due to Polanski's legal problems in the US, but set in the vicinity of Brooklyn Heights. The Cowans' son Zachary hits the Longstreet's Ethan with a stick, resulting in the loss of two teeth. The Cowans come to visit the Longstreets to prepare a reconciliation between the two boys and by way of apology. Things begin in a polite, civilized manner, over apple-pear cobbler and coffee. As the evening wears on, whisky is drunk, and hostilities -- evident from the start -- grow stronger. Casualties include Kate Cowan's vomiting, which damages Penelope Longstreet's treasured art books; Kate throws her husband's ever-present cell phone into a vase of water; and she later trashes a beautiful arrangement of tulips that ornaments the coffee table.

I confess that the Broadway Gods of Carnage left me unmoved, quite specifically due to my memory of being shaken to the core by the original Broadway Virginia Woolf. It might have been interesting to see Isabelle Huppert in the Paris version, but I'm not sure. However you slice it, this is much ado over an 11-year-old's smashed incisor and it's not Pinter or Martin McDonagh. It is a pleasure to see Polanski's elegant and very well-directed version, but why has the New York Film Festival not chosen any Polanski film but this since Knife in the Water? What about Chinatown? The Pianist? Is this, like the Oscars, some belated gesture of recognition?

Carnage was shown at the Venice and New York film festivals, screened for this review at Lincoln Center. The gala opening night presentation of the NYFF. It will be a Christmas bauble for Americans, opening in theaters December 16, 2011 (Sony Classics). It opened rather widely in Italy September 19th (355 screens) and has done rather well.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2011 at 09:26 PM.

-

Asghar Farhadi: A Separation (2011)

ASGHAR FARHADI: A SEPARATION (2011)

PEYMAN MOADI AND SARINA FARHARDI IN A SEPARATION

How everybody's wrong, and why

Jodaeiye Nader az Simin/Nader and Simin, a Separation is the full title of this new Iranian film that uses neorealist vérité style to weave a tangled skein of quarrels and legal problems (and implied class conflict) that occur when a secular middle-class family clashes with a more impoverished one after the better-off husband and wife choose to split up. Notable for an unusually intricate and well-worked-out plot that poses many moral issues while remaining curiously bloodless in human terms, Separation almost gets bogged down in the numbing specifics of telenovela-like daily melodrama at first as it sets up its basic issue. When if finally gets going the film takes on almost a mystery-story complexity and, if it's never quite resolved at the end, well, that's life. With this web of fault-finding and recriminations that somehow cancel each other out, in A Separation Asghar Farhadi may have made the quintessential Iranian film.

The basic setup, unfortunately also the least involving scene, shows Nader (Peyman Moadi), a bank employee, faceing the camera alongside his wife Simin (Leila Hatami) as a judge considers Simin's request for a divorce. She has had permission to emigrate for some time; its validity is soon to run out. She wants to take their teenage student daughter Termeh (Sarina Farhadi, the director's own daughter) out of the country for a better life. Nader refuses to go. He feels he must stay to care for his Alzheimer-sufferer father (Ali-Asghar Shahbazi). The judge finds Simin lacks sufficient reason for divorce. She is stuck in Tehran, but goes to stay with her mother (Shirin Yazdanbakhs). Termeh remains with dad and her senile grandfather, of whom she is fond.

To cope in Simin's absence, Nader hires the poor and devout Razieh (Sareh Bayat) to mind his father during the daytime, and Razieh brings her little girl (Kimia Hosseini). The film follows Razieh and her daughter only for several sequences when they're at Nader and Simin's apartment. Razieh turns out to be pregnant, and also unwell. She isn't really able to cope with an Alzheimer's patient and when he wets himself, has to call a religious advisor to know if it is lawful for her to help him clean up and change. When she isn't looking he escapes and goes out to the local newsstand. She goes off, chador flying, to find him and bring him back. A day or so later Nader returns to find Razieh and her daughter out and his father fallen on the floor unconscious with one arm tied to the bed. He and Termeh restore the old man to consciousness, afraid at first he might be dead. Nader finds some money missing. When Razieh returns, he fires her. She protests, claiming she had to go out and did nothing wrong, and in the altercation Nader grabs Razieh and pushes her out.

The next day he learns Razieh is in the hospital and has had a miscarriage. Simon and Nader, who reconnect to deal with this emergency, go to see her. They encounter Hodjat (Shahab Hosseini), Razieh's short-fuse husband, who has met Nader but didn't know his wife was working in a strange man's house and caring for another strange man, and would never have allowed it. Before you know it we're back in front of a judge in a crowded police station, with Nader accused of murdering Razieh's unborn son (she was 4 1/2 months pregnant) and Nader counter-charging Razieh with assaulting his father.

This is essentially where the film begins as claims go back and forth and the points of view become increasingly complicated. One issue is whether Nader knew Razieh was pregnant, and the testimony of Termeh's female tutor (Merila Zarei), who had a conversation when Razieh first arrived that Nader may or may not have heard, becomes key. Another issue is: did Nader knock Razieh down the stairs, or did she fall? Neighbors testify. And then: What caused the miscarriage? Did the violent Hodjat (who's already come to blows with Nader) hit her? He has been in and out of prison due to debts, is out of work, and is at his wit's end. His angry vociferation clouds every meeting.

A Separation is a realistic picture of a culture in which everyone is quarrelsome and out of sorts, everyone finds fault with everyone else (with the exception of a few sacred parental and filial family relationships), and everyone lies -- but both secular and religious values have strong positive sides. Nader is stubborn and macho, but also surprisingly open in offering his wife and daughter the choice of how to act. And call it religion or superstition, but though Razieh may lie, she is not willing to do so under oath, for fear of dire consequences from God.

The virtue of this film as of many contemporary Iranian ones is the way it is completely rooted in believable quotidian details. And the main actors, whom Farhadi, whose original background was in theater, had thoroughly coached and conditioned, are quite convincing even if their characters remain opaque and unsympathetic. The claim by some that this is a kind of "Rashomon" seems, on the other hand, quite absurd: the camera sticks very close to Nader's point of view and rarely has scenes without him. The strategy is to follow one event after another in the legal wrangling for what it may reveal of new evidence and new testimony. At one point Nader is in jail and must be bailed out by Simin, and he might be sentenced to from one to three years in prison. But this isn't a film about character so much as about legal, moral, and religious issues. The strategy of constantly revealing new details or accusations may seem irritating, but it keeps your attention and builds up energy, even though a sense of overarching structure is, perhaps intentionally, lacking.

A Separation has won praise for its ingenious plotting. It's a kind of puzzle-film, more intricate than suspenseful (the comparison with Hitchcock is as silly as the one with Kurosawa) -- and with a tension that dissipates rather than is resolved. In addition to being ingeniously plotted and well-acted, however, it's good looking by Iranian standards, with handsome, if sometimes jerky, camerawork by d.p. Mahmood Kalari, who's a mean man with a yellow filter.

Though his name is new to some of us (including me) this is the 39-year-old Farhadi's fifth film, and he has won prizes before, particularly for his 2009 About Elly. A Separation has been shown in a raft of international film festivals, starting with the Berlinale in February 2011, where it won the Golden Bear and the Best Actor and Best Actress awards, and ending with Rio and the New York Film Festival, where it was screened for this review. It has been or will be released in a dozen countries, with limited US release (Sony Pictures Classics) coming December 30, 2011.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-29-2011 at 11:43 PM.

-

Santiago Mitre: The Student (2011)

SANTIAGO MITRE: THE STUDENT (2011)

ESTEBAN LAMOTHE AND RICARDO FELIX IN THE STUDENT

Macchiavelli in academia

In this present-time tale that might have unfolded in any of the last five decades, the smooth-talking Roque Espinosa (Esteban Lamothe) returns to the University of Buenos Aires from his rural hometown for the third try, having begun studies there before in two different schools and dropped out. This time he finds his real areas of specialization: women and politics, in that order at first; politics, never an interest of his before, takes the lead once he's found a political activist girlfriend who's a low-level faculty member. Largely through Paula (Romina Paula) he learns how adept he is at using his people skills as a political fixer, organizing a grassroots protest and an assembly and meeting sub rosa with high officials to help a professor friend maneuvering to win an election. But that adeptness betrays him. His final and most important word in the film's closing image is a "No" that probably is the beginning of his real life.

A recurrent voiceover introduces us to the politically naive Roque as he enters the campus, full of political graffiti and slogans and words that are going to become his daily bread in a while, but at first are a mystery. He doesn't know what the talk of political parties or curriculum reform is all about at first, but he's more attracted to Paula, who gives a confident political speech, than Valeria (Valeria Correa), the less cute girl he's bedded since arrival. He's a bit of a Casanova, a quality that doubtless adds to his political charisma as time goes on. He soon becomes fascinated not only with Paula, but with the older Peronistas he meets through her, veterans of the 1970's "dirty war" who engage in dialectical conversations with the younger and more skeptical political leftists around the university, who gather plotting ways to gain control of an academic board. This material may elude some non-Argentine audiences, but would strike familiar cords for Europeans and other Latin Americans nonetheless, and seen simply as a picture of an election campaign's nitty-gritty aspects, is pretty universal.

What's lacking after the first few scenes, surprisingly, given that this is a university setting, is much focus on fundamental ideological and doctrinal issues. As Roque is befriended, and used, by a professor, the experienced politician and friend of Paula, Alberto Acevedo (Ricardo Felix), what seems to be going on is mainly just horse-trading to gain position and win elections, and we lose sight of what makes all this worthwhile, other than gaining Roque a respect among members of his chosen university party that, it turns out, can be easily lost. What does come through loud and clear is Roque's eventual disillusion when he realizes despite being given good jobs to do for a newcomer, in the end he's just a pawn in a game he doesn't control or understand.

Argentine writer-director Santiago Mitre's El estudiante is a study of university politics that's richly detailed and specific. So much so that, particularly if one is reading the fast appearing and disappearing English subtitles, it's sometimes hard to follow. And it tends to overwhelm its protagonist, Roque, who is less interesting than the machinations he becomes a part of. We might say the same for the director. Discovering his own skill at anatomizing the bait-and-switch schemes of leftist academics arranging to win key posts, Mitre gets in a bit over his head, as Roque does, losing sight of his film's need to breathe a bit. But no matter. People are starved at some level for this kind of thing. Accurate depictions of politics of any kind are rare. The Student has won admiration and attracted filmgoers in many countries already.

And this is not to fault Esteban Lemothe, the lead, or Mitre. Lamothe is an interesting actor, energetic and sexy without being really handsome, suave yet not quite sophisticated. He's a little like Malik Zidi in Emmanuel Bourdieu's Poison Friends (NYFF 2006), another film about a university student's disillusionment. And Mitre, who has written two screenplays for Pablo Trapero, Lion's Den and Carancho, knows how to build moral unease and maintain an intense pace. Los Natas' score, heavy on strings and drums, is good at maintaining the sense of youthful excitement, and creates a wonderful mood of disenchantment in the last scene. The team camerawork is good at maintaining a sense of Roque's point of view in crowded shots. For all its weaknesses, this is a lively and vivid film with a fresh subject. I see his point, but I don't find this "dry and inconsequential" as Mike D'angelo did, writing from Toronto.

Indiewire trumpets Mitre as "a South American Aaron Sorkin," and this film does make one think of Sorkin's White House and presidential campaign saga created for American television, "The West Wing." But Sorkin is way more in control of his material, and that allows him to entertain and develop character while unfolding his political intrigues from multiple viewpoints. These are skills that elude Mitre, who sticks doggedly to the POV of Roque, so doggedly that things are more wearing than witty in the Sorkin manner, though the film still delivers intense, compelling stuff. It's fun trying to keep up with all the endless political talk. When it's over, though, The Student may seem a bit short on memorable moments.

The Student debuted at the Buenos Aires festival in April 2011 and was shown later at Toronto and Hamburg and the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-12-2019 at 10:58 PM.

-

Ullrich Köhler: Sleeping Sickness (2011)

ULLRICH KÖHLER: SLEEPING SICKNESS (2011)

PIERRE BOKMA AND JEAN-CHRISTOPHE FOLLY IN SLEEPING SICKNESS

Up river

The German director Ulrich Köhler's third film, Schlafkrankheit in the original, is about Africa, where he lived happily as a boy, by his own account, when his parents were European medical relief personel in the Congo. His film is in two parts, which don't mesh particularly well. The first part is about a Dutch-born doctor, Ebbo Velten (Pierre Bokma), who's been in Cameroon too long and says goodbye to his German wife (Jenny Schily) and teenage daughter (Maria Elise Miller), but can't bring himself to leave. The Mr. Kurtz analogy would be excessive: the locals seem quite tame, for one thing -- but Velten has become one of those culturally split personalities who can't quite fit in in either world, this one or the one he left a long time ago. The second half comes three years later when Alex Nzila (Jean-Christophe Folly), a young French doctor of Congolese descent who's lived all his life in Paris, arrives on his first assignment from WHO to do an assessment of Velten's local program to eradicate sleeping sickness. Good performances, believable incidents, and totally authentic locales don't make this come together as a well-made film. It becomes increasingly unfulfilling as it progresses. The writing and editing are at fault here, but Sleeping Sickness won a festival slot (and even a Silver Bear award at the Berlinale for Köhler's direction) through its interesting and lived-in subject matter and atmosphere.

Velten loves his German wife, but an unappetizing bed scene shows their sex life may have died out. Yet when Gaspard (Hippolyte Girardot) suggests he join up for some play with pretty young African women, he declines. That has changed when the screen goes black and the narrative resumes, three years later, focused on Dr. Nzila and France. Velten's interest in African women has developed now, three years later, when Dr. Nzila arrives in Cameroon to do the WHO evaluation. Things are rough for Nzila: even getting from the airport is a huge hassle. By now, it turns out, Velten has a young African wife about to have a baby. Velten is off somewhere, his underlings covering for him as Nzila frantically waits. Nzila is even called on to perform a Cesarian section, which he has never done and doesn't even have the stomach for. And then he gets sick. Nzila goes through a series of scenes that are vivid images of a westerner plunged into a primitive setting and far out of his depth. He's also treated differently because he's black, dumped off at a hovel in the dark of night when he first arrives.

When Velten finally shows up several days later, treating the ill Nzila and performing the cesarian, which turns out to be on his wife, it also gradually becomes clear that sleeping sickness has been so nearly eradicated through Velten's good offices that the program and funding aren't needed. We've already seen in the first part of the film that Velten acknowledges this but local bureaucrats want more funding, not less. Velten isn't really needed either, most likely. He's trained the locals, and done himself out of a job. But of course he has no life elsewhere. What is Nzila to do?

That question is never really answered. Köhler takes Gaspard, Velten, and Nzila hunting by night along a river, and we get a whiff of a Heart of Darkness situation as Nzila becomes terrified and is separated from the other men. The film's ending is open-ended, which is fine, except that the contrast between Velten and Nzila, who are obviously polar opposites of the colonial spectrum, is never developed in an interesting or revealing way. Velten has a certain sleazy charisma. But it's the first shocking days of Nzila's mission that leave the most vivid impressions. In his final moment, after a night alone, he comes to the river's edge dazed and is pushed into a long rowboat. Gaspard and Velten are nowhere to be seen, and as the boat slips away a large, menacing hippo appears. It's a memorable moment -- this film has a few -- but a completely ambiguous one.

It's hard not to compare this with Claire Denis's White Material, also a treatment of Europeans in Africa whose time has run out. Though Denis isn't at her best in that film, it certainly develops the whole colonial-African context far more clearly and richly. Köhler's specific local details are very convincing, more intimate and real in an everyday sense than Denis', but he doesn't do enough with them. Denis' Africa may be more mythological and generalized, but it's also more resonant.

Sleeping Sickness debuted at Berlin in February 2011, and was released in Germany, the Netherlands and Poland in June, July and August, respectively. It was chosen to be part of the New York Film Festival in October, and it was screened there for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-12-2019 at 06:05 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks