-

DANIELE LUCHETTI: OUR LIFE (2010)

NICE is the acronym for the New Italian Cinema series presented by the San Francisco Film Society.

ELIO GERMANO IN OUR LIFE

Getting away with working class graft

Italians are crooked and only care about money, is what several foreigners tell Roman construction worker Claudio in this engaging if somewhat slapdash and too easily resolved tale, whose indestructible protagonist is played by Elio Germano, the older brother in Lucchetti's richer and more successful political family chronicle from 2007, My Brother Is an Only Child. Like that film this one is a vivid artifact of Italian life, this time of the present moment. Even more than before, Lucchetti makes things too easy and breey; again he steeps the action in humor, warmth and the sound of Roman dialect.

The screenplay gets Claudio into a terrible mess and then in a rapid succession of spliced-together final scenes delivers him from it without a scratch. First his wife (Isabella Ragonese) dies giving birth to their third child. At the funeral, with everybody else -- but the cozy handheld camera used throughout focuses only on him --he screams out the raucous song he and his wife liked to sing between sex sessions, Vasco Rossi's "Anima fragile." But once that's out of the way the scrawny, smiley Claudio sheds barely a tear.

More a bother for Claudio than the loss of his wife but also a benefit is the foreigner at the building worksite, a Romanian, who he finds buried at the bottom of an elevator shaft. A watchman, the man died in a fall, and the boss hid the body because the site might have been shut down otherwise for employing illegal workers. Greedy, Claudio half-blackmails his boss Porcari (Giorgio Colangeli) into giving him a whole building project. But he has to morrow the money from his pimp-drug dealer neibhbor Ari (Luca Zingaretti) and must hire illegal aliens as the workers. Their work is lousy. Ari's Senegalise ex-whore girlfriend takes care of Claudio's kids, including the two cute young boys and Vasco, the baby. Also in and out of the scenes is their controlling sister Loredana (Stefania Montorsi).

Meanwhile the dead Romanian's wife Gabriela (Alina Madalina Berzunteanu) and her son Andrei (Marius Ignat) turn up. Embarrassing? Not for Claudia. He fixes up Gabriela with his handsome loner brother Piero (Raoul Bova) and hires her incompetent chubby son on the construction site.

As the project goes from one disaster to another, the film cuts rapidly from scenes at work to domestic developments. We have to believe the heard-hearted Porcari's change of heart and the family members' chorus of "We are here," meaning they will always bail Claudio out, as somehow they do. Illegal money sifts in from all directions, a new crew is hired, of illegal but more expensive and more reliable emergency Italian workers, and, well, Claudio has a good cry and everybody's happy. Whether his idea that material success would make up for his kids the loss of their mother is a dumb one or just needs more successful hustling to come through is a question that is not dealt with. The film makes hasty social and political points at the cost of emotionally connecting with the audience.

The hasty, handheld and jump-cut resolution is ridiculous, but somehow this film's content is awfully Italian, not least the tricky deals and tax dodging, as well as the racism, the problems with foreigners, the illegal workers, and the loyalty of family. Though he's too shrill and manic here, and registers too few real emotions, Germano is a talented actor, and the other cast members are confident and appealing. The action, however rushed and too easily resolved, is thrown at us with energy and momentum. So that, in Italy's lackluster current movie scene, will have to do.

Our Life/La nostra vita was in competition at Cannes 2010 and Elio Germano shared the Best Actor prize for his performance in the film with Javier Bardem (for Biutiful). Screened for this review as a part of New Italian Cinema, a series presented by the San Francisco Film Society at the Embarcadero Cinemas, San Francisco, 13-20 November 2011. Our Life was the opening night film, starting off a mini-series of Lucchetti films and shown at 6:30 9:30 November 13.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-18-2011 at 08:50 PM.

-

CLAUDIO CUPELLINI: A QUIET LIFE (2010)

TONI SERVILLO IN UNA VITA TRANQUILLA

Things are not what they seem

This is a slow-burning thriller and it has one of the best Italian actors of recent years in it, Toni Servillo of Il Divo, Gomorrah, The Girld by the Lake, and The Consequences of Love. He is Rosario, an Italian running a nice hotel and restaurant in Germany, with a German wife Renate (Juliane Kohler ) and a nine-year-old son. His past comes back with the arrival of Diego (Marco D'Amore) and Edoardo (Francesco Di Leva) two burly and explosive young men. One of them turns out to be Rosario's grown and resentful son, whom he has not seen for many years. Rosario is delighted to see Diego, but he and his "colleague" are obviously up to no good. A few words Rosario speaks to his son show he too has been in big trouble, so the atmosphere of quiet and respectability can quickly be broken if circumstances cause him to slip back into the old mode.

Cupellini creates a constant atmosphere of danger and trouble on the way -- even sous-chef Claudio (Maurizio Donadoni) seems potentially violent -- while maintaining a sense of underlying calm and routine and not overdoing anything. Servillo dissolves into this mysterous ex-pat life as he does with all his roles. He has a look of polite indifference, but turns on a charming smile for important guests. He lights up whenever he looks at Diego -- until things change. The cinematographer, Gergely Poharnok, makes judicious use of reflections to hint that nothing is as it seems. Heavy Neapolitan accents in a German resort area itself conveys menace..

Servillo's role here could be seen as a variation on Paolo Sorrentino's elegant The Consequences of Love, where he is explicitly a mafioso exiled, in quarantine, but here rather he is is hidden away, living a new life, "a quiet life." The obvious danger is that he can slip back into the old mode if the old dangers and violence break into the quiet. Comparisons are odious, but it's obvious that the cold, routinized character Servillo plays in Sorrentino's film is less appealing, but more interesting than this warmer fellow, and this is more a conventional thriller. But it provides pleasures nonetheless. When the trouble starts it's not half over. And for those of us choking on blockbusters, it's a treat to see a thriller that's a slow burner that's character-driven. In the plotline, as it finishes, there's a pleasing aftertaste of Patricia Highsmith. This, like The Consequences of Love, takes a little to long to end, but it's an excellent sophomore effort by Cupellini, and not only Servillo (as usual) but D'Amore and di Leva, a well-matched pair, interesting and complex characters who far more than just young gangster types. (Renate is a bit underdeveloped as a character.)

Screened for this review at the New Italian Cinema series presented by the San Francisco Film Society, running 13-20 November 2011 at Embarcadero Cinemas, San Francisco. (Another film in this series stars Toni Servillo: Andrea Molaioli's The Jewel/Il gioiellino. )

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-03-2014 at 02:07 AM.

-

ANDREA MOLAOLI: THE JEWEL (2011)

TONI SERVILLO AND REMO GIRONE IN THE JEWEL

"We'll make it all up"

The Jewel/Il gioiellino reunites Andrea Molaioli with the great Toni Servillo, whom he directed in his previous film, the much-celebrated 2007 "existential" police procedural, The Girl by the Lake/La ragazza del lago, which I reviewed as part of the Lincoln Center New Italian Cinema series in New York in June 2008. Molaioli previously worked a lot with Nanni Moretti, which may help explain his interest in social and political issues. This new film is based on the true story of the bankruptcy of the Italian company Parmalat. Servillo plays Ernesto Botta, the chief financial officer, the right hand man of the boss Amanzio Rastelli (Remo Girone). The names are changed, the events would be familiar to Italians.

Rastelli, who has the regal air of a captain of industry, inherited a sausage factory from his father and grandfather and in several decades, by the Eighties, turned the business into a multinational food conglomerate and global dairy producer called Leda. It's the "little jewel." But Leda is like the Lehman Brothers surrogate in the new film Margin Call, only instead of credit default swaps, the weak underpinning that can't survive the stock market boom's sudden fade is a network of bribes of politicians and financial authorities. LIke the Depression era Ponzzi schemer in the recently revived 1963 Terence Rattigan’s drama Man and Boy, Rastelli and Botta are swinging back and forth, between Moscow and New York in this case, trying to raise the money to stay afloat, and the cops are waiting in the wings.

Officers of the company waste money on luxuries, and Rastelli has his football team and airplanes. Botta mostly just watches and frowns: Servilli's performance is a controlled display of bitchy temperament. You should hear the language he uses when he talks to American bank officials, in English -- he can't hear himself. He fights Rastelli's neice Laura (Sarah Felberbaum) when she's put in his office. Then she turns out to be smart and he has an affair with her. Perhaps it's to make this seem more plausible that much older Servillo wears a hairpiece for this role. But it doesn't work: the affair seems sterile and worse yet, a narrative misstep. For a while this turns into a portrait of Botta. Maybe the filmmakers just became overly fascinated with the by now famous Servillo. He can anchor the film but the story is not about him. An episode in which Botta and Laura confront an American bank officer in New York verges on the absurd.

Like The Girl by the Lake this film takes its time and rambles, and this time some of the sequences are of dubious value. It's nothing like Margin Call, which stunningly depicts a spectacular failure that takes place in 24 hours. We watch Leda hovering on the verge of failing for years, and if this weren't a financial thriller, if it weren't the very timely story of a major crime, this could be a very dull movie. Rastelli keeps bringing the company back from the brink, and when he finally gives up Botta jumps in. "We'll make it all up," Botta finally says. Filippo Magnaghi (Lino Guanciale), the young commercial director, sees through the imposture, can do nothing about it, and jumps off a bridge. As he and another executive are take away in the paddy wagon, another executive says, "We had some golden years, though, didn't we?" Botta just glowers into the distance. This film has its flaws, but it's timely and it's got the steely ill humor of Toni Servillo, and the crocodile endurance of Remo Girone, as his boss, is a strong performance too. The corporate design credits -- logos, products, publicity, the grand company offices -- are also all very well done. Several scenes in a Russian church and in the snows of Moscow are handsome. The picture is nice to look at.

Screened for this review as part of the New Italian series presented November 13–20, 2011 at Landmark's Embarcadero Center Cinema by the San Francisco Film Society. The other film in this series starring the remarkable Toni Servillo is A Quiet Life, a crime thriller directed by Claudio Cupellini.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-31-2017 at 12:08 AM.

-

GIAMBATTISTA AVELLINO: SOME SAY NO (2011)

PAOLA CORTELLESI, LUCA ARGENTERO, AND PAOLO RUFFINI IN SOME SAY NO

"These things in Italy aren't Mafia; they're normal"

Some Say No is a new Italian comedy with a very serious subject: the way the country's society is corroded by favoritism that pushes inferior people to the top in virtually every field. In Florence, three thirty-somethings band together to wage their own war on the system. Each of them is a person of talent who has been pushed out by "favorites" or raccomandati, people who have muscled in on the promotions they ought to have gotten by pulling strings.

Max (the handsome, energetic Luca Argentero) is a talented journalist on a local daily newspaper, just about to be permanently hired, when the daughter of a famous writer gets his job and his boss is too spineless and dependent on the preference system to oppose the move. Irma (Paola Cortellesi, underrepresented here) is now one of the best younger doctors at her hospital. She is just about to sign onto a permanent contract when the head physician’s new Australian girlfriend (Harriet MacMasters-Green) receives the post instead. Samuele (Paolo Ruffini, the real comic actor of the three) is a brilliant young expert on penal law. After years of virtually unpaid scholarship and teaching, he's just learned that his academic chair is going to his boss’ sleazy and thoroughly incompetent Lothario of a son-in-law. Ten years of exams, degrees, and fine performance in training positions have added up to nothing for this frustrated trio. They're hopping mad.

Max, Irma and Samuele compare notes and decide to get revenge on the three who have usurped their rightful positions, trading victims to avoid detection. They call their little band, which later on they hope to expand into a movment, "The Pirates." Samuele's stipulation is that they commit no high crimes. However, they don't stick to that rule. Things go so well Samuele hires local gangsters to harras Irma's rival and her porky husband. Max winds up wooing the woman reporter who got his job, as well as, briefly, Irma. Since the victims -- especially the head doctor and his Australian wife -- have had their pet birds disappeared and mock-roasted and their front door walled up -- have protested to the authorities, this also turns into a comical fumbling police procedural. It is not by accident that the filmmakers have the cops distracted by this minor matter from investigating the serious threat of Eastern European gangster activity.

This plot exists to deride and mock various Italian contemporary social issues, most notably people who get positions they don't deserve, but the pill is made very sweet indeed by the entertaining infusion of comedy, romance, and risk the filmmakers have devised. The mix is both classic and timely. The details of upper-bourgeois elbow-rubbing and the universal acceptance of immoral behavio are very much of today' Italy. It's made very clear how the system of racommandati is endemic, undermining values and performance country-wide. This is a "national social and democratic comedy," as one Italian review (Marzia Gandolfi, mymovies.it) called it. But the social comedy mocking greed and incompetence belongs to a world familiar to the audience of Moličre or Goldoni.

Avellino has worked a lot in TV comedy. This is his third feature. This is a comedy too, but it's energized by very real and justified anger at Italy -- questo paese di merda,, as they call it, "this shitty country" -- for its overwhelming system of nepotism and graft.

Screened for this review at the San Francisco Film Society presentation of the New Italian Cinema series for 2011 at the Landmark Embarcadero Center Cinema. It's the international premiere of C’č chi dice no, 95 min. Written by Fabio Bonifacci andGiambattista Avellino. Cinematography by Roberto Forza. The film was distributed (in Italy) by Universal Pictures International. It was released April 8, 2011 in Italy and is now available there on DVD.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-27-2011 at 09:33 AM.

-

GIORGIA CERCERE: THE FIRST ASSIGNMENT (2010)

Making do in the boonies

A beginning teacher in Fifties Pugila (down toward the rugged heel of the Italian boot) gets sent far from home and far from her well-off fiancee to teach in a tiny one-room school in this first film as austere and lacking in excitement as the world it depicts. The lackluster action is offset by the sprightly, natural turn of rising star Isabella Ragonese in the main role of Nena. Ragnese also appears in two other new films chosen to be in the 2011 New Italian Cinema series, Our Life and One Life, Maybe Two, though it's only in this one that she has the major role. Unusual for a young leading lady in being rather plain, she is a little like Betsy Blair of the memorable Fifties films Marty and Calle Mayor: beyond the plainness, there is a poise and presence and something potentially touching and sad about her that holds one's attention.

She's given precious little to do here, however. There is a subtlety about the film and it has cute little touches provided occasionally by Nena's small students in the rural school, but there is very little talk, many of the scenes are made less involving by being shot from the middle distance, and there are no interesting characters other than Nena herself. The fiancee, Francesco (Alberto Boll), is a virtual nonentity. Then when his taking up with a wealhy woman leads Nena to sleep with a local handyman and she must harry him, we get the earthy but noncommittal Giovanni (Francesco Chiarello, another newcomer, like Boll), who may have a pulse, but just barely. In his review of the film for Variety at Venice in September 2010 Jay Weissberg wrote: "Playing it safe at every turn, Cecere turns in the kind of unexceptional drama, light and only mildly entertaining, that fills up satcast movie channels condescendingly geared toward women." He calls the film "unexciting and uninvolving."

Mostly Nena's story is about making do in the boondocks. She seems contemptuous of the villagers and then gradually seems more and more willing to put up with them. She goes from being considered unfit to teach to getting congratulated by an education administrator for her good work. The ragtag urchins (who are little represented but very cute) turn out to be teachable. But what about Francesco, who has changed everything by meeting another more upper class woman? The ending of the film is ambiguous. Cecere's film storytelling is so understated that at times it feels like it isn't clearly stating anything.

The odd coolness of the style, which sets it apart from most Italian films, may explain how Cercere's debut came to be received reportedly with great enthusiasm at Venice. Let's hope future work justifies this interest. The First Assignment/Il primo incarico, however, is not likely to make a big splash in the world at large, apart from some critical success. Despite a confident, though intentionally understated, turn by Isabella Ragonese, there's virtually no there there.

Cecere was nominated for the Controcampo Italiano Prize at Venice, and Ragonese and the production designer Sabrina Balestra received nominations for the Silver Ribbon at the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists. Screened for this review as part of the San Francisco Film Society's presentation of New Italian Cinema, a series shown Nov. 13-20 at Landmark's Embarcadero Center Cinema in San Francisco.

-

ALESSANDRO ARONADIO: ONE LIFE, MAYBE TWO (2011)

LORENZO BALDUCCI IN ONE LIFE, MAYBE TWO

Two roads diverged....

In his first feature One Life, Maybe Two/Due Vite per Caso, Arnadio treads the familiar path of alternative lives ŕ la Sliding Doors. The variation is that this takes us into the very contemporary world of a young middle class Italian with ordinary prospects and some rough experiences ahead of him. The film opens up when two guys rear end a cop car. Or, more accurately, there are two alternative lives that split off when Matteo (rising young star Lorenzo Balducci) has to brake for a stationary car. In the action-packed first version, he hits it, and he and his friend are beaten by the plainclothes cops, particularly one plainclothes cop (Ivano De Matteo), and he is taken in and charged; his friend Sandro (Riccardo Cicogna), who has cut his finger, goes to the hospital. This sends Matteo's life in a certain direction, he stays at his job in a plant nursery, and besides pursuing his own case, he gets involved in radical politics. In the other version, he stops just short of hitting the car and there's no unpleasant confrontation with the cops.

In this life, he gets fed up with his lack of prospects in his job and goes into training with the Carabinieri, the national police force. The film goes back and forth with sequences of the two alternative lives, using a more saturated palette to distinguish one life from the other. Certain events are independent of whatever Matteo does and exist in both versions, such as the heart attack of his father Pietro (Teco Celio). A Czech named Ivan (Ivan Franek) met in a bar seems to invade Matteo's life bringing a trail of sleaze. There are two women in Matteo's life,. He has a crush on a pretty barmaid, Sonia (Isabella Ragonese, of The First Assignment), at the club he and his friends hang out at, Waiting for Godard. He has also met and become involved with a girl from a good family, Letitia (Sarah Felberbaum, of The Jewel). The core idea is that a guy his early twenties doesn't know where he wants his life to go and it couls spin in many different directions; and the story appeals to young audiences in the same situation. On the other hand, Matteo seems to encounter frustration and anger and end in violence in both versions, whether he rear ended the cop car or not. The film is freely based on a story by a story by Marco Bosonette, "Death of a Confused 18-Year-Old," and references Truffauts 400 Blows, particularly the freeze-frame ending down by the beach. The handsome, sweet-faced Balducci seems like victim being prepared for slaughter in harsh economic and political times.

If you watch for philosophical profundities or even telling interrelationships between the two alternative narratives you will not find them. If, on the other hand, you watch for scenes of how Italians live, work, and talk now, this movie is fresh and alive and well made. Above all you can watch it for views of the appealing and handsome young star Lorenzo Balducci as Matteo, and he does a good job of seeming like the same guy in both narratives and thus providing a unifying strain. The film reads better as a series of somewhat unrelated slices of life than as a consistent or enlightening narrative. But Aronadio has a conclusion: he brings his two alternative lives together a the end to suggest that despite variant actions, a person's path winds up in the same place.

Theis is a highly competent work but is also unfortunately yet one more example of the fact that the once great Italian film world has lost its once distinctive and powerful direction; the effect for all the skill in shooting scenes winds up feeling overall a bit timid, tentative, and sketchy. Whether or not Aronadio will develop a distinctive style and viewpoint remains to be seen. However, this film shows mainstream talents and Alessandro Aronadio has an excellent background.

Born in Rome in 1975, Aronadio has written fiction and scripts for film, and is a photographer with a degree in psychology who wrote a thesis on David Cronenberg. He studied film in LA on a Fulbright fellowship. He has worked with Luc Besson, Giuseppe Tornatore, Mario Martone, Roberto Andň, and in the US on a series of independent productions. He also directed commercials, videoclips, short films, and documentaries.

One Life, Maybe Two was screened for this review at the New Italian Ceinema series produced by the San Francisco Film Society at Landmark's Embarcadero Cinema, Nov. 13-20, 2011. Due vite per caso debuted at Rotterdam in January 2010 and was released in Italy May 7, 2011. Also shown at Berlin and at Cannes (out of competition). Jonathan Pacheco's The House Next Door (Slant) has a smart discussion of this film written in connection with its showing in NYC in June 2011 as part of the Open Roads Italian film series at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-03-2014 at 02:05 AM.

-

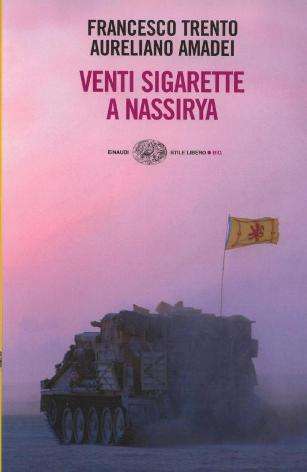

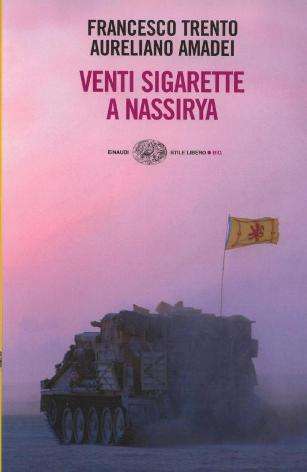

AURELIANO AMADEI: 20 CIGARETTES (2010)

VINICIO MARCHIONI AND ALBERTO BASALUZZO IN 20 CIGARETTES

Film slacker's Iraq war tale

20 Cigarettes is autobiographical account in three parts of an experience of the then 28-year-old Amadei in Iraq in 2003. Based on the book he co-authored with Francesco Trento, Venti sigarette a Nassiriya (Twenty Cigarettes in Nassiriya, Einaudi), the film is lively but patchy and uneven in its tone. In its attempt to be amusing about deadly serious matter, in some parts it's curiously tasteless, strange, and off-key. There is the danger of a kind of pathetic fallacy here that the film falls prey to almost immediately and recovers from imperfectly -- of feeling as frivolous and half-cocked as its protagonist is pretty much all through. The fact that the tragic event he gets inadvertently involved in was big news in Italy adds considerable interest to the film for Italians. The tonal issues and choppiness are minuses for others.

From the start the smiling, curly-haired Aureliano (Vinicio Marchioni) seems like an overgrown child, playing games with a camera in his hand. It's telling that when he goes to Iraq, completely on a whim, he forgets to bring his camera long, though using it was the purpose of the trip. A sometime anti-war demonstrator who escaped military service by pretending to be gay, Aureliano has vague filmmaking aspirations, but he's far from there at this point. Boyd van Hoeij of Variety <a href="http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117943441?refcatid=31">calls</a> this story "the incredible (and incredibly irresponsible) work experience of an Italo slacker." The Italian soldiers he's around, evidently not key to Bush's "shitty war" (as A. calls it) are goofballs too. Aureliano goes because his mother is friends with director-producer Stefano Rolla (Giorgio Colangeli), who wants to do a fiction feature in Iraq and is asking her to donate $5,000 and offering the smiling 28-year-old aspiring filmmaker boychick a chance to come along. "It'll be a real job," says his mom (Orsetta de Rossi, a Laura Dern lookalike). "Not as an actor, though," Aureliano protests. He's supposed to go in a couple of days. But he's about to be in a demonstration against the Iraq war.

Good story.

And very soon after he gets there, Aureliano gets blown up in a suicide bombing. Yet he survives. And that's the payoff.

In the first section taking the protagonist from his slacker life to a truck bombing in Iraq, the film is good at making great leaps. It jumps back and forth between the Rome takeoff and the Iraq arrival, the swinging handheld camerawork evoking the good natured recklessness of the protagonist. He's got a spoiled life, with a ditzy but simpatica upper bourgeois mamma and two girlfriends, lovely "best friend" Claudia (Carolina Crescentini), whom he occasionally has sex with, and an official "fidanzata" from Rio, the superstitious Angela (Desirče Noferini, merely glimpsed).

Amadei's signal of the absurdity of the desert combat zone of Nassiriya, with its US PX "megastore" and Burger King, is that when he's off the plane and wants a cigarette, he has to go off to a tiny island of confinement surrounded by sandbags as a "smoking area." The conclusion of part one is an atmospheric collection of trivia as Aureliano settles in with the soldiers and Rolla, his boss, Massimo Ficuciello (Alberto Basaluzzo), their official bodyguard, who's the more sympathetic because he's a reservist, not regular army.

20 sigarette has in common with David O. Russell's Three Kings a sense of the palpable harmony between the absurdity of the Iraq war setting and the unpredictable danger it harbors. Frivolity is jammed up willy-nilly with seriousness. The picture's location shooting (actually filmed in Morocco) has a realistic feel, and so does the explosion, which comes in part two. The first part of part two is shot literally from Aureliano's P.O.V., initiated by having Aureliano wipe the sand out of his eyes and reopen them. This intense P.O.V. makes the truck bombing and Aureliano's injuries more vivid. Though the modest budget keeps this from being as rich in detail and context as The Hurt Locker, Amadei deserves much credit for creating an intense battle sequence midway.

According to a Guardian <a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2003/nov/12/iraq.italy">report</a> the Nov. 12, 2003 Nassiriya bombing killed 25. Included were 17 Italian soldiers and military police and two Italian civilians, including Stefano Rolla, the director of the film Amadei was supposed to work on, and at least eight Iraqis. When this happens 20 Cigarettes jumps momentarily into horror movie style, with Aureliano panting and groaning, the screen filled with his blood-covered arm clawing its solitary way forward through the rubble. After that: hysterical soldiers, objects, chaos, tragic news, an American hospital, and a few more cigarettes.

Part three is the aftermath back in Italy starting three days later as Aureliano recovers from trauma and leg injuries, a badly mangled ankle. In the Rome hospital, after all the moaning and weeping that's gone before, comedy abruptly returns with Tino (Edoardo Pesce), a clownish male nurse who offers to give out cigarettes and joints to all patients. Aureliano is now a hero because he miraculously survived, and a media circus surrounds him, along with squabbling with other survivors and maudlin moments.

Amadeo the director lacks the dry touch necessary to carry off comedy while presenting a tragic incident of war. His account of his own experience is vivid but jarring and overdone.

20 sigarette debuted at Venice Sept. 5, 2010 and had its Italian release Sept. 8. It was screened for this review as part of the New Italian Cinema series (Nov. 13-20-, 2011) presented by the San Francisco Film Society at the Embarcadero Center Cinema.

THE BOOK

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks