-

Aleksandr Sokurov: Faust (2011)--FCS

ALEKSANDR SOKUROV: FAUST (2011)--FCS

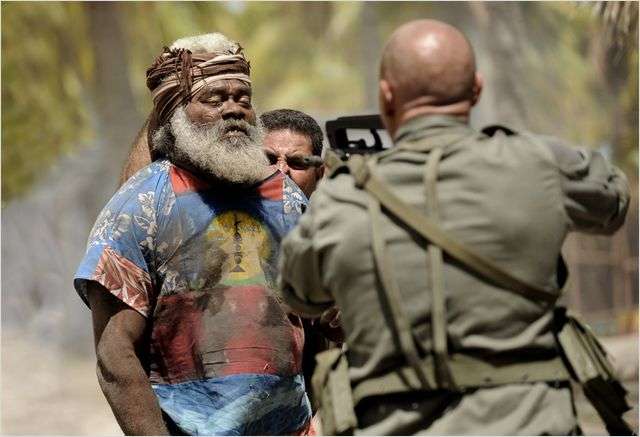

JOHANNES ZEILER AND ANTON ADASINSKY IN FAUST

Sokurov's very strange and visually remarkable version of 'Faust'

Aleksandr Sokurov's Faust won the top prize, the Golden Lion, at the Venice Film Festival in September 2011. Gavin Smith, the editor of Film Comment, introduced the FCS series and this film at the Lincoln Center Walter Reade Theater by saying that this was probably the only chance audience members would get to see it on the big screen. Indeed other than his big US art house success, the tour-do-force one-long-take trip through a museum with music conducted by Valery Gergiev film Russian Ark, Sokurov's films have rarely gotten theatrical releases Stateside. And Faust is not a likely candidate. The grubby opening sequence included hoisting up a naked cadaver whose guts fell out, which sent half a dozen people from the theater. When giving the Golden Lion, Darren Arronovsky announced that it was the kind of film that could change your life forever. Sokurov's films are remarkable as they are off-putting and strange. Most are haunting and hypnotic. Alexandra, (NYFF 2007)about an old woman who visits her soldier son at the front, is moving. The Sun (NYFF 2005), an incredibly sensitive portrait of the Emperor Hirohito in the time up to and after the Japanese surrender, is a hypnotic, revealing, and extraordinary touching portrait. Father and Son is as sensuous and homoerotic and strangely beautiful as any film about men ever made. Like many of Sokurov's films it exists in a foggy hyperreal dreamworld that is complete but only partly parallel to our own.

Faust, which like Sokurov's Moloch, is in German, announces in its opening titles that it is based on the work by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, but interprets the legend of the man who trades his soul to the devil to gain knowledge in a very peculiar manner. This Heinrich Faust (Johannes Zeiler), who follows the traditional pattern in being a learned scientist, is linked up with a strangely annoying and grinning busybody of a devil with a pear-shaped body and scraggly reddish hair. He is a moneylender (Anton Adasinsky). Faust has become attracted to Margarete (Russian actress Isolda Dychauk), a pure young woman with pale skin and flaxen reddish hair, and it seems that his bargain is to give up his soul for a little time spent with her. Some "Faustian bargain."

The mood of Sokurov's Faust, as Variety reviewer Jay Weissberg has emphatically noted, is different from most of his other films in its ceaseless nattering verbosity. Mostly Sokurov's mood- and image-centric films contain few words but this one never stops talking. What with its voiceover from Faust or conversation between him and the moneylender, or the rambles of the moneylender, the soundtrack here keeps a constant chattering rhythm going like an outboard motor continually running. Sokurov thus creates and maintains a kind of peculiar energy and a sense of a world that is going on just beyond us, inside the screen so to speak. Sokurov has done this before, but this time the sense of a world that we can't quite penetrate is a little different. In other films we feel swept away (Russian Ark) or enveloped and hypnotized (Father and Son, The Sun). Here we are more alienated.

He counts this as the last in his tetrology about the corrupting effects of power. Those that I have seen (I'm missing Taurus, about Lenin) have little in common with each other. Moloch (1999) deals with Hitler in 1942, in Bavaria, and focuses on a visit to Eva Braun by Hitler, Goebbels, Goebbels' wife and Martin Bormann in which they sit around for several days talking about politics. The Sun, as mentioned, is an intimate portrait of the Emperor Hirohito.

What distinguishes Faust, which seems otherwise one of Sokurov's brilliant misfires, are the images and the mise-en-scène. Weissberg comments that the photography echoes Flemish painting and also folk art about witches. This may be so, but what seems even more striking is the way the director has recreated the look and feel of early photography. One could also not help but be reminded in the early sequence of Faust's laboratory of the photographs of Joel-Peter Witkin. And this gives a sense of how rich and elaborately staged and photographed the interiors and exteriors are and how convincing the people and costumes are in their sense of period. Beyond that, the framing of exteriors, the peculiarities of aspect ratio and focus, and the complex "gray" tonalities all build up the nineteenth-century look. Jim Jarmusch's Dead Man is an analogy, but here the effect is richer -- and stranger.

Manohla Dargis has commented on a shot as unforgettable. It's one where Faust is united with Margarete and he embraces her and they flip over together into a river. It's a dream-image, symbolic rather than real. And the whole film is best understood as what Dali and Bunuel might have done if they'd gone on working together and done their version of Faust. But there's just a gutted corpse here, no dead donkeys lying inside a grand piano. I still remember the late Graham Leggett introducing Sokurov's The Sun at a press screening for the 2005 New York Film Festival saying this was one of the world's great directors: the sheer boldness and conviction with which Leggett made the statement left a lasting impression. And somehow it still rings true.

Seen for this review as part of the Film Society of Lincoln Center's series, Film Comment Selects. Screening times:

Friday, February 17 at 8:15PM, Tuesday, February 21 at 3:15PM and Tuesday, February 28 at 9:00PM.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-23-2012 at 06:01 PM.

-

James Franco: My Own Private River (2012)--FCS

JAMES FRANCO: MY OWN PRIVATE RIVER (2012)--FCS

A chance to see a lost actor at work

James Franco was fifteen when Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho came out. He has said that it is his favorite film, it moved him, it helped shape him as a teenager. After he worked on Milk he went to see Van Sant and learned that he had kept 25 hours' worth of film footage shot at the time of My Own Private Idaho. Franco has written about the experience.

"We spent two days in Portland watching as much as we could. While we were watching, we discussed how Gus’s movies have changed in the intervening decades. His films now are much more spare in story and dialogue; they involve longer takes and fewer cuts. We were naturally led to wonder what Idaho would be like if he made the film now, and Gus offered to let me make my own cut."

Franco seems to have made three films, or maybe two that were combined. They've been shown at Toronto and put in an installation in LA at Gagasian Gallery, when Franco got Gucci to pay the cost of digitalizing the many hours of film Van Sant turned over to his use and the gallery agreed to present Franco's piece. The Gagasian installation is described in a Guardian blog, "James Franco brings River Phoenix back to life,"and now appeared at the gallery across from the entrance to the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center in New York where the Film Comment Selects series is shown. This was a shabby-chic version of an AA meeting, with scattered mismatched camp chairs and romantically tacky hanging gold and orange drapery, a table with a coffee urn and paper cups, a color film projected on a big screen at one end of the room and a small screen at the opposite end high up with a film in black and white on a monitor. (The latter turns out to be the Shakespeare material that Franco chose to leave out.)

I did not go to the Film Comment Selects' late evening event at which these were handsomely projected in their combined form on the really big screen with a Q&A by Franco at the end, because this was sold out. But I got the feeling from the faux AA meeting installation, which was one of sadness mixed with respect for the talent of River Phoenix. Van Sant's film gives us fragments of a lost life, love, hope, comical sad hustles, love and disappointment. River Phoenix delivered other notable performances. At a memorial service after his death Sidney Poitier, who worked with him on one of his films, called him "incandescent." It's surprising to see that what would seem to be a child role, Stand by Me, comes only two years before Phoenix played a precocious, gifted youth in Running on Empty, and a mere five years before the layered complexity of My Own Private Idaho.

It's interesting that James Franco has done these pieces and Van Sant let him do them. Whether or not there are more long takes in Franco's edits, Idaho was a highly improvisatory production with a lot of people hanging out and living approximations of the dissolute lives the film chronicles. (This is brought out more because Franco stressed the documentary aspect of the film footage.) Rumor had it that there were a lot of drugs and some said the atmosphere gave Phoenix a push toward the downward path (his death from an overdose came two years later). But what the extra takes and footage show of Phoenix is of him living the sensibility of his character, Mike, the narcoleptic gay street hustler. Phoenix had in some sense lived on the street, since he and his siblings reportedly entertained on the sidewalk to make money when very young, and this is how River became a performer, as a street singer and busker. We can see Phoenix turning talk about nothing into seamless rifs on Mike's sad aimlessness and longing for home and love. We can see him turning stage business over pasta at the table in Italy to an expression of his jealousy and sense or rejection. He is so expressive you hardly need the movie, or the dialogue.

In a page Franco published in The Paris Review he talks about the many alternate takes that go into any movie. Mostly the ones not used are thrown away. But "sometimes—as when they feature an actor like River Phoenix in a film like My Own Private Idaho, the best of his generation giving his best performance—every scrap is gold." So here simply we have some scraps of gold gathered by James Franco with the collaboration of the original filmmaker, Gus Van Sant.

The interest for students of acting is to see a gifted actor "in character." It's playacting so good you can't see when it starts and stops.

While the installation went on for several days, My Own Private River was a one-time event of Film Comments Selects at the Walter Reade Theater of Lincoln Center.

Sunday, February 19, 2012 at 9:00PM.

James Franco attended and participated in a post-screening Q&A.

There is a Film Comment Q&A with Franco avaiable online . Franco says Phoenix in the film (and rushes) often seems like "a cross between James Dean and Charlie Chaplin."

Visitoers hanging out in the "My Own Private River" installation, Walter Reade Theater Feb. 2012, seem like

Gus Van Sant characters.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-23-2014 at 07:12 PM.

-

Hirakazu Koreeda: I Wish (2011)--FCS

HIRAKAZU KOREEDA: I WISH (2011)--FCS

Oshiro and Koki Maeda in I Wish

Watching bullet trains, choosing the world

In 2004 Koreeda made a wonderful but sad film about children, Nobody Knows. I Wish is another one, nearly as fine, but much happier -- though again it has children dealing with unreliable parents (just not as bad). There are superb scenes in which kids are charming and real. But I Wish moves around much more than Nobody Knows. In that one, four siblings are abandoned together by their radically irresponsible mother and must try to survive in their apartment on their wits. This gives Nobody Knows, perforce, unity of place. I Wish skips around, as it must, because this time there are two brothers who are now living with separate parents. At one or two points I Wish says a little bit too much in the mouths of babes, but it also contains moments of such beauty you wish they would never end. Probably some of the magic comes from the fact that the film stars real-life brothers Koki and Ohshirô Maeda who already had their own sibling comedy act, Maeda/Maeda.

Are Japanese kids cuter and happier than other children? Sometimes it seems so. Whatever the case, these qualities feed into the magic moments that abound in Koreeda's new film. I Wish isn't an unqualified success. It may ride too much on its cuteness and its magic. Or Koreeda may have been too reluctant to cut any of the cute or magical moments, which -- due to his success as a director of children and documentary filmmakers and the charm of his young cast -- kept multiplying. As a result his film meanders and sprawls. But it's possible meandering and sprawling are Koreeda's way no matter what his subject is. He isn't a director who likes to move fast. Note how patiently he wanders through the long summer day in his 2008 Still Walking. The meandering is deceptive. The film builds, and when it's got all its force together it hits you with a quiet emotional wallop. Koreeda creeps up on you.

But I Wish is deceptively random-seeming and deceptively simple and "accessible." There is as much order here as there is complexity. This may be Koreeda's most accessible film but it's up with his best and most original work. And what it's all about may not become clear till later.

The story focuses on a child's urban legand: the idea that if you can see two new bullet trains crossing paths the wish you make then will come true. The two brothers talk on the phone. They're apart now because their parents couldn't get along. Their mother Nozomi (Nene Ohtsuka) found their musician father Kenji (Joe Odagiri) totally unreliable, so she moved back in with her grandparents (Isao Hashizume, Kirin Kiki) to work in their little supermarket as a cashier, taking the older brother, Koichi (Koki Maeda), a sixth grader. The small but lively Ryunosuke (Ohshiro Maeda) goes to the big city of Fukuoka with his dad, a rock musician who's never quite successful enough to do without other work but can't stick to a conventional job. We get a few looks at the parents' former squabbles, but mostly we focus on Koichi and Ryo. It seems as though it's Koichi who most wants to get back together. A chubby, perhaps more staid chap, Koichi may be a bit jealous of Ryo's new friends, who include the prettiest girl in class, Emi (Kyara Uchida). He chafes at life with the grandparents, and is annoyed by the volcanic ash of Kagoshima, where he now lives. Obviously life with their laid-back dad and his band-mates is cooler, even if life with mom is more reliable.

Koreeda is skillful at managing three plots: the life of Ryo, the life of Koichi, and their project to meet midway to observe the two bullet trains and make their wishes, which finally takes over as a group "road picture" with a subtle kind of "resolution" that avoids conventional feel-good aspects with moments that may make you cry but none of the saccharine tear-jerker outcome ordinary filmmakers would have made with this plot outline.

Part of the time is spent following Koichi and his classmates and their dislike of a teacher (Hiroshi Abe) and crush on a school librarian (Masami Nagasawa). Meanwhile Ryo becomes the pet of a group of girls including an aspiring young actress s (Kyara Uchida) whose failed actress mom (Yui Natsukawa) keeps telling her daughter she will fail. Back with Koichi, grandma is learning hula dancing and grandpa and his cronies drink and tweak an old-fashioned (comically tasteless) cake recipe which some think can be sold as a novelty tie-in with the new bullet train.

None of this matters so much in dramatic terms except for the way it all creates a three-dimensional world going in various directions linked by the bullet trains and the boys' bullet train project. The scenes of the children are particularly sprightly and winning, and the progress of the film is punctuated by the linking cell phone chats between the two brothers. The wish-making meeting involves fellow classmates, money-raising (the tickets are expensive), permissions for a 24-hour absence from school, and a lot of logistical planning. The wish-making project takes on a metaphorical meaning: the journey becomes the destination. Making the wish as the bullet trains cross paths turns into one of those childhood myths, like the tooth fairy. In the event, the boys find themselves discovering a new outlook, or choosing "the world," as Koichi puts it. But that thought and those final sequences are just something to hang your hat on. I'm sure the deepest truths of I Wish are buried in the laughter of classmates, the cell-phone conversations, or Ryo's fava bean-growing. This is film that will obviously profit from repeated viewings.

The score by the soft rock group Quruli may seem more ingratiating than necessary, but it helps underline the youthful good spirits that prevail; maybe Koreeda is consciously creating an antidote this time to the deeply downbeat feel ofNobody Knows. The reassurance of I Wish is that parents in modern urban society can part without the children's being left abandoned or desperate. These kids are good at fending for themselves but they also have good adult support.

I Wish (128 minutes, cinematography by Yutaka Yamazaki) debuted at Toronto September 2011 after a June theatrical release in Japan, and has been at numerous other festivals, including Rotterdam. It enters French cinemas in April 2012. It was also included in the Film Society of Lincoln Center's 2012n Film Comment Selects series shown at the Walter Reade Theater, where it was screened for this review. It showed to the public as part of the series at these dates and times:

Sunday, February 19 at 6:15PM and Monday, February 20 at 8:45PM.

Koreeda's I Wish is being distributed in the US by Magnolia Pictures and will open in New York at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas and Angelika Film Center May 11, 2012.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-16-2013 at 10:20 PM.

-

Mathieu Kassovitz: REBELLION (2011)--FCS

MATHIEU KASSOVITZ: REBELLION (2011)--FCS

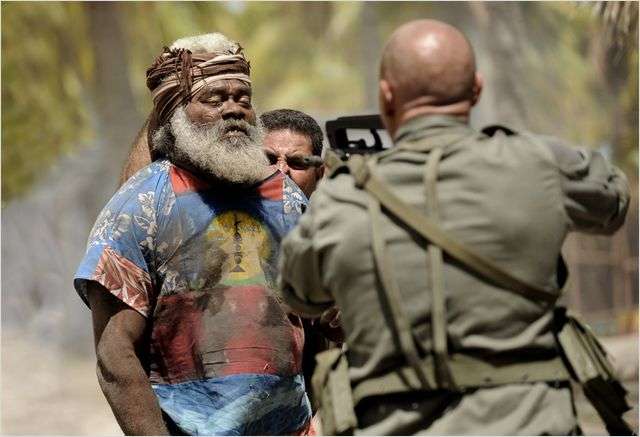

Kassovitz's smart actioner

Mathieu Kassovitz's Rebellion, which he directs and stars in, is about the revolt and hostage-taking that occurred in 1988 on the tiny Pacific island of Ouvea in New Caledonia that was put down by its French rulers. This is an intense action film about shocking historical events -- one that effectively goes beyond the action format to show how politics trumps military and diplomatic considerations. Kassovitz has to that extent made a war movie for smart people. and this isn't a crude polemical piece but a deftly executed film with high production values full of elaborate set pieces and showing a superb and natural sense of place. Note however the limitations of personal POV: this is the arguably one-sided account of one man, a main player (as he saw it anyway) and based on his published memoir of events. The good man surrounded by military puppets is a well-told tale that provokes thought -- and one of the best new political films from the French in some time as well as a great leap forward for Kassovitz as a filmmaker -- even if it is not a work of sublime complexity.

We begin with the violent finale. Then we go back to the beginning, from the narrator's point of view when GIGN (French national police intervention group) Captain Philippe Legorjus was sent out to New Caledonia with his personal team because locals who rebelled independently (separate from the French-branded "terrorist" independence insurgents, the FNLKS -- Le Front de libération nationale kanak et socialiste) -- had taken some hostages in two places and killed a few people in the process. Negotiation in such crises is Legorjus' job, and he is sent the 23,000 kilometers with his own team. As he sees it since New Caledonia is French territory the rebels are French, and should be treated with the respect accorded French citizens. The action is limited and he has no doubt -- this remains true to the bitter end -- that it can successfully be contained by negotiation.

But it's 1988 -- in the middle of the 12-year socialist presidency of François Mitterand when opposition from the right is virulent. An election is coming very soon. Right-wing PM Jacques Chirac leads a conservative cabinet. The Ouvea revolt and hostage-taking becomes a tool of their conflict. Both sides must take a strong position on it. And this will be fatal for Legorjus' negotiations.

Kassovitz's film shows excerpts from a debate between Mitterand and Chirac that took place in the middle of the events. The two politicians take opposing views, but the film overlaps their remarks after a while depicting them as merely a political blah-blah-blah. The point is that the issue has to be resolved before the election and to do that, negotiating would take too long. Politics intervenes and negotiating is doomed. He doesn't quite know it yet, though Legorjus and his team arrive to find the French army already deployed in alarming numbers, for a tiny rebellion (ten to one, anyway): heavily armed intervention by special assault troops is already a foregone conclusion.

It's a tribute to Kassovitz's well-executed film that it tells a complicated step-by-step story over a ten-day period with great clarity and including action on many levels. And this involves meetings with the main leader, the hostages, and many communications back and forth by Captain Legorjus with the local military in charge, the government minister sent to New Caledonia, the general to whom he must report, and CIGN government liaison in Paris. He also meets with the leader of the insurgent Kanaks FLNKS. The leader of the rebel hostage-takers, Alphonse Dianou (Iabe Lapacas) is depected perhaps as too gentle and sweet to be true. But you have to grant that Kassovitz is making a smart person's action movie but still an action movie, and this is not a mini-series: he turns in the whole story in a fast-moving 135 minutes, so there is come simplification. The complexities of the New Caledonian independence moviement are left aside. A newcomer to the topic might think what had gone on for a century had just arrived last year.

Advocates of the government or even of the CIGN, who might wish to argue they acted correctly and not simply under pressure are not so pleased with Kassovitz's anti-colonialist analysis, but the basic principle is a universal one. Issues are crudely resolved to satisfy the needs of an election. White soldiers quelling a non-white rebellion 23,000 kilometers from home are not likely to be gentle. They tortured. They massacred. Captain Philippe Legorjus fought a desperate race against time to carry out negotiations before the attack and almost got killed doing it, but -- spoiler alert! -- in the end (it's where the movie begins) he didn't get to do the job he had been trained to do. As Legorjus, Kassovitz has that same neutral, easy-to-identify-with quality ha had in his iconic early role as the young con man in Jacques Audiard's early A Self Made Hero/Un héros très discret. Other good cast members: Malik Zidi as JP Perrot as Legorjus' second in command; Alexandre Steiger as Jean Bianconi, a local negotiator; Sylvie Testud as Legorjus' wife; and a host of Kanak people and Frenchmen who make the scenes come alive and look right.

Rebellion is a misnomer. The French title is L'ordere et la morale, Order and Morality, an ironic tag that leaves us with a tonic dose of frustration instead of the usual catharsis. This is Kassovitz's most significant directorial effort since his important 1995 film about class in France, Hate (La Haine), and this time he is working with a bigger concept and a bigger budget and project.

Rebellion is a film that debuted at Cannes and also showed at other festivals, including Toronto and London. It opened in Paris November 16, 2011 to very good, if not great, reviews (Allociné 3.2); some critics understandably see the film as fine, but flawed; perhaps some did not see how much is done well here, but they did see that Kassovitz produced a creditable effort after serious missteps and the entertainingly lurid The Crimson Rivers. Rebellion was also included in the Film Society of Lincoln Center's series, Film Comment Selects, where it was screened for this review (Feb. 29, 2012).

-

Nadine Labaki: Where Do We Go Now? (2011)--ND/NF

NADINE LABAKI: WHERE DO WE GO NOW?--ND/NF

NADINE LABAKI IN WHERE DO WE GO NOW?

A nice fantasy

Lysistrata with song and dance and hashish cookies is what Nadini's sophomore effort is, a benign fantasy of how a Lebanese village might stop its deadly Muslim-Christian clashes if all the women just switched religions and hid their men's weaponry after getting them very stoned. The film is a charmer -- it's sort of as if the gut-wrenching Incendies were redone as a Don Camillo tale directed by De Sica with help from the Taviani brothers -- and it's the kind of movie you get if you mix up handsome young men, pretty women, lusty old ladies and chubby geezers in a grab bag of different physical and personality types located in a quaint hillside town. Labaki herself is one of the stars and she's a looker. (Her star-crossed would-be Muslim beau is played by Claude Baz Moussawbaa.) There's able cinmatography by dp Christophe Offenstein and plasing music by Khaled Mouzannar. The screenplay is from Thomas Bidegain, who collaborated with Jacques Audiard on the script of The Prophet.

Everybody gets together, plays together, sits in the localcafe together, watches a scratchy TV together. Just outside town there is the village cemetery, full of handsome young men, with the Christians on one side and the Muslims on the other. Though the women have taken over there's still a pair of corpses to be buried at the end, one Christian and one Muslim, and that's what the title is about. Since they women have switched religions ("I'm on the other side now"), which side do the coffins go to? it is a nice fantasy.

Where Do We Go Now? has hectares of charm and local color. Its Lebanese Arabic is the saltiest language imaginable, especially what comes of those feisty old dames' mouths. There is some Russian and English too, which comes from a totally unnecessary, and not at all glamourous, little troup of Russian women brought in to entertain and distract the men. As if we needed another distraction. Labaki likes to keep new stuff happening. She showed that in her debut, Caramel, which was less ambitious and a little more successful, and told a ronde of love and family stories centered on the employees and customers of a Beirut Beauty parlor. The only trouble with this method is that the audience never identifies much with any one person. In this new film we may have trouble even identifying members of the ensemble at times, especially with the young men, who don't wear outfits to tell us which religion they belong to.

The lack of strong emotion is more evident when the sectarian strife built into the Lebanese DNA takes its toll and the tone turns tragic. As Alissa Simon of Variety wrote, this "genial and at times genuinely inventive" film tickles the funny bone' but never quite 'taps the emotions.' She also notes "problems of tone, pacing and performance." Nonetheless when it played in Paris last fall (as Maintenant on va où? it was well received (Allociné 3.7, with even more enthusiasm from the public), and the charm goes a long way. This was also Lebanon's entry into the competition for the Best Foreign Picture Oscar, but not a finalist.

I originally reviewed Where Do We Go Now? when I saw it in Paris (Oct. 27, 2011). As I pointed out, reviewers with several of the more sophisticated French publications were cunimpressed at Sept. 14 release time, though though did play in a lot of locations (and Caramel had had a French run in 2007 and a US one several years later). This is a feel-good movie with enough likability to carry it through a theatrical run, and may be enjoyed for years to come, but though it has lots of color, many of even the best scenes are derivative and not memorable.

Where Do We Go Now is included in the March 21-April 1, 2012 New Directors/New Films series, put on in New York by the Film Society of Lincoln Center jointly with the Museum of Modern Art. It's the opening night film. Showtimes:

Wednesday, March 21st | 7 PM | MoMA

Wednesday, March 21st | 8 PM | MoMA

(Where Do We Go Now? has been picked up by Sony Pictures Classics for US release, as has the other press screening of today, Garth Evans Indonesian-language martian arts action film The Raid.)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-23-2014 at 07:14 PM.

-

Gareth Evans: The Raid: Redemption (2012)--ND/NF

GARETH EVANS: THE RAID: REDEMPTION (2012)--ND/NF

The ultimate fight picture?

The Raid runs for 100 minutes. Be prepared. Most of it is violent fighting in a dark ghetto building 15 stories high. Fighting with automatic weapons and pistols but mostly with machetes and knives and hand-to-hand, to the death, on and on, to the last man. This is as dark, intense, violent, and extreme a movie as you will ever be likely to see. And for about 90 minutes you are trapped in the halls and apartments of that grey, dingy building with vicious and desperate men. If that appeals to you, have at it. If not, please don't come to watch this movie.

A SWAT-style attack squad of policemen comes to rout makers of illegal drugs housed on the top floor of a tall building. But some of the squad are tyros, inexperienced in such raids. And they are expected. The building is dark and dingy but fitted with a full system of security cameras. It also has a speaker system. And it seems to be crawling with lithe, long-haired men in loose, greasy T-shirts, carrying long machine guns and out to kill anything that moves. Not only are many of the policemen quickly killed, but for the rest, the escape route seems blocked. When the cops have been decimated and only the strongest survive, the lithe bad buys keep coming on one floor after another, carrying knives and out to kill. They keep on coming and coming. Only a handful of cops survive and make it to the top floor. And their fight is the longest.

"I am the guy that makes stunt performers take multiple kicks to the head for what I hope is a captivated audience," says Gareth Evans, a Welshman who as a child wanted to be Jackie Chan. He was later a fan of Die Hard and Assault on Precinct 13 -- "films that used a single building for unyielding cinematic geography while creating feature-length tension." Then he went to Indonesia and learned about Pencat Silat, a traditional kind of martial arts fighting using the body and blades and teamed up with Iko Uwais, a young, almost baby-faced champion of the sport. He first starred in Evans' debut, Merentau. The Raid will seal Evans late-night martial arts movie cult status. In The Raid, Uwais plays Rama, a young cop with a pregnant wife. And then there is Joe Taslim, who plays Jaka, and Yaya Ruhian, who plays Mad Dog.

The aim is to bring down the calm, sinister drug lord on the top floor, Tama (Ray Sahetapy). He watches the battle with Andi (Doni Alamsyah) and Mad Dog on his battery of screens. A complication, besides the fact that a lot of the cops are unfit for this kind of urban warfare, is that the raid instigator, Lt. Wahyu (Pierre Gruno), is corrupt and may have devious motives that can lead to the failure of the operation.

While Tama's ragtag army has downed most of the cop squad, it emerges that Rama is a relentless superman. After a while the focus is on his continual downing of opponents. There is also a wounded cop whom a building resident with a sick wife takes in, hiding him and Rama till Mad Dog breaks in.

Evans skillfully structures the action (which was created interactively, the stunt men and martial artists creating their fights according to what he calls "a D.I.Y. method of fight choreography," with the film team, cameramen, and editors) so that it rises and falls, with changes in rhythm and what he calls "breathing space" -- calculated pauses so the audience can catch its collective breath. For the faint of heart this is simply unpleasantness, but for those who like martial arts movies, this is a new kind of pleasure. The fight choreography is superb. Pencat Silat is a rough kind of fighting, with running and tackling and improvisation of weaponry. There is also some judo, where brawn is more a feature. There are leaps and twists. Moti D. Setyanto's production design makes use of the building, where holes are punched so men can jump or climb between floors, and there is the feel of an endless but inescapable labyrinth.

It's awesome, it's relentless, and toward the end it's a bit absurd, how several guys can get beaten up, then untied, and fight tirelessly in a threesome for endless minutes, then run away. The most tireless bad guy fights for minutes with a candle driven into his throat. There is a satisfying finale involving capture of the crime boss, punishment of the corrupt cop, and a reunion of brothers who are on opposite sides. All ready for Berandal ("Thug"), the sequel, which is coming, with Uwais again as Rama. The director sees The Raid now as the first of a trilogy. Obviously Evans, whose team for shooting, editing, sound design and two music tracks for Indonesian and western audiences is crack, is in deep debt to Hong Kong. This would not exist without that. But the dark Kafkaesque ironies of the action evoke Park Chun-wook and the Korean revenge film of recent decades too.

The Raid: Redemption or Serbuan Maut presented at Toronto, followed by Sundance and SXSW. It has been picked up by Sony Pictures Classics. US release will be March 23, UK May 18, 2012. It is included in the MoMA/Film Society of Lincoln Center New Directors/New Films series, to be shown:

Thursday, March 22nd | 6 PM | MoMA

Thursday, March 22nd | 11 PM | FSLC

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-05-2012 at 09:35 PM.

-

Mohammad Rasoulof: Goodbye (2011)--ND/NF

MOHAMMAD RASOULOF: GOODBYE (2011)--ND/NF

LEYLA ZAREH IN GOODBYE

Another quintessential Iranian picture

Mohammad Rasoulof, who has done intriguingly poetic films like Iron Island (2005) and The White Meadows (2009), has come down grimly close to home with this claustrophobic, cold study (everything is blue gray and nearly everything is close up and indoors) of a woman lawyer trying to get out of the country. Like Rasoulof himself, she is having visa problems. Like the woman in Asghar Farhadi's recent much honored A Separation, she wants to leave Iran. Her life has been shut down by the regime. Her right to practice law has been taken away and she has lost her cases. Her husband, a journalist, has had his newspaper shut down and is operating a crane on an industrial construction project in the south of the country. She has gotten pregnant. She was told to by a man we never see, who takes money to help people leave. And it turns out late in the film that her child will have Down Syndrome. What a nightmare! But she only cries once, and that is muted, her shoulders shaking as she lies face down on the bed.

Leyla Zareh, as the lawyer, with her beautiful long-suffering face, looks like Ingrid Bergman. It's good that she's beautiful, because we have to spend a lot of time looking at her. Her little apartment contains nothing but her and a turtle. Across from it is the airport, and that and the turtle who escapes after she puts it in a larger container and apparently dies or disappears, are blatant in a way that Rasoulof has not been before. His experience has robbed him of his detachment and his cinema has lost its poetry.

Goodbye is a punishing film, impeccably made, perhaps, with its clean looking digital images, with a few nice shots and enough specific detail to make you, if you can stand it, pay attention. But it's basically very thin on artistry, though the stress on chilly office putdowns make this seem another quintessential contemporary Iranian film. After seeing it at Cannes Mike D'Angelo gave it only a 49 and wrote: "More political statement than movie. Even as a movie it’s on shaky ground, with the symbolic turtle and so forth." But it is a movie, a conventional movie, almost an instructional film. (If it were only that it would be a notable one, because instructional films don't usually get actors as good-looking as Leyla Zareh). No, it's a little more than that but a lot less than Jafar Panahi's This Is Not a Film, which was also at Cannes, and linked with it because they were both smuggled in and added to the festival at the last minute. Both men were arrested with more than a dozen others at the same time, and jailed, but unlike Panahi, Rasoulof has not been officially banned from making films. Ironically, Panahi, banned from filmmaking, made a film that is self-referentially witty and ironic and strong. Rasoulof, not banned, has made someting blatant and obvious and tedious. Farhadi, well, he has made a film that to me is annoying, but it is intricate and neatly constructed and a picture of Iran's problems that is, relatively, warm and full of life, but to say that is to see just how chilly and empty Goodbye is.

Commenting from Cannes on mubi's online Notebook, Daniel Kasman seems to share my dissatisfaction. He finds Goodbye repetitious, lacking in deput, "a cyclical dirge," and sees it as "cloaked and variably choked by both the clandestine nature of the film's production and the hushed and desolate story it tells." Yes, we must applaud both Panahi and Rasoulof for their smuggled-out cries of protest against their country's repression. But Panahi's film is intriguing and this one is numbing. Simon Abrtams calls it "too literal and pat." Nonetheless, predictably, there were raves, and Alissa Simon in Variety predicted that "fest and niche arthouse play can be expected."

Goodbye was also released in France in September and shown at Toronto and in other festivals. It was watched for this review at a press screening for the MoMA-Film Society of Lincoln Center New Directors/New Films series.

Goodbye (Bé omid é didar, in Farsi, 104 min.)

Thursday, March 22nd | 8:30 PM | FSLC

Saturday, March 24th | 1:00 PM

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks