-

Alain Resnais: YOU AIN'T SEEN NOTHING YET (2012)

ALAIN RESNAIS: YOU AIN'T SEEN NOTHING YET (2012)

Layers of memory, layers of performance

The 89-year-old perpetual experimenter Alain Resnais' latest film, Vous n'avez encore rien vu, more catchily rendered in English as You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet, is a conceptual piece about classical theater and the way actors internalize key roles they have played. Call it meta-theater, if you will; like most of the veteran New Waver's more recent works, it eschews the cinematic in favor of the elegantly stagey. Everyone is well groomed and impecably dressed. There is one modern touch: a big flat-screen TV. In the opening credits sequence, thirteen well-known French actors are summoned (by their real names) to one of the many estates of a theater director, Antoine D'Anthac (Bruno Podalydès), whom they're informed has just died. When they get there the deceased's butler acts as master of ceremonies and clicks on the TV where a pre-recorded D'Anthac welcomes them and announces they will watch and comment on a new warehouse-staged production of Jean Anouilh's 1941 play Eurydice, which they have all played in. (That play is a source for the film, and also another play by Anouilh, Dear Antoine.) But when the younger cast goes into action, the thirteen veterans alternately take up their lines. What all this adds up to is anybody's guess. There's something soothing in the formality and artificiality of the proceedings. But their failure to go anywhere and the extreme repetitionsness of the film will keep it from playing well to a non-festival audince.

At first the actors, who include Resnais' wife and longtime muse Sabine Azéma, Michel Piccoli, and Matthieu Amalric as well as Lambert Wilson and Anne Consigny, are sitting around in big black armchairs. Then as the young actors speak, they begin not just mouthing lines with them but getting up to say them, and at times they are injected by green screen into the play's two main settings, a train station restaurant and a shabby hotel room. There are three sets or actors who have played the couple, Orpheus and Eurydice: present in the mansion for the ceremonial observance set up by the late director are Pierre Arditi+Sabine Azéma and Lambert Wilson+Anne Consigny; on screen in the youthful warehouse version, Sylvain Dieuaide+Vimala Pons.

The older actors sitting around in the mansion played Eurydice in the past, so their return to their roles may also evoke their own past, and perhaps ways in which their own lives and Anouilh's classical Greek characters are intertwined in their minds. Perhaps they're trying to return to their youth. With actors of this quality (and they are the best) and staging, filming, and editing on an equally high level, there is some pleasure in watching this business. But when the person nearest me at the screening dozed off I was not much surprised. As Peter Bradshaw wrote in the Guardian about the film when he saw it at Cannes, "despite its moments of charm and caprice, the film is prolix, inert, indulgent and often just plain dull."

Often but not always, and it would be foolish to watch this and find no meaning in it. Bradshaw note the obvious fact that the Greek theme of Orpheus refers to nostalgia, a thing an old artist might well be thinking much about. The theme of Orpheus partly means that "by looking back at her in the underworld, he loses her," as Bradshaw puts it, suggesting Resnais may be saying looking back is stifling and we must live in the present, no matter what. Mike D'Angelo in tweets from Cannes rated the film highly in his severe system, 73 (below Moonrise Kingdom though and well below Holy Motors) and called it Resnais' "fond farewell, ruminating on the end, his career and the nature of cinema and theater," adding that it seemed "So audacious in conception initially that it wasn't quite sustainable," adding cryptically that it was the film he'd wished Prairie Home Companion had been. You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet is interesting to think about, not so involving to watch.

Vous n'avez encore rien vu debuted at Cannes; it will be released in Belgium and France Sept. 26, 2012. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-07-2016 at 04:06 PM.

-

BEYOND THE HILLS (Cristian Mungiu 2012)

CRISTIAN MUNGIU: BEYOND THE HILLS (2012)

COSMINA STRATAN, CRISTINA FLUTUR IN BEYOND THE HILLS

Long takes, short life

Mungiu's griping, if one-note, new film comes from a 2005 news story that caused a big stir in Romania: a girl went to visit a friend at a remote nunnery and died while its members, led by the priest in charge, were performing an exorcism on her. But the director revised the story into his own style, taking the non-fiction novels of atiana Niculescu Bran as a starting point. Elaborate action sequences are shot in long widescreen takes, like Naranjo's Miss Bala; only this is nothing like Miss Bala: these are two girls and a group of nuns scurrying around up on a hill. What Mungiu also added was the history of a relationship, studiously not (quite) lesbian but certainly intimate and deeply loving, between the two girls when they were growing up in an orphanage. So the unfortunate visitor, Alina (Cristina Flutur), a somewhat mannish young woman who has been lonely in Germany without her friend and has lost touch with her foster parents, arrives at the nunnery with no one, hoping her beloved Voichita (Cosmina Stratan) will come away with her. But Voichita, who originally only came for a visit herself, has by now taken Jesus and the local priest's very austere, judgmental form of Eastern Orthodox Christianity as her new world and comfort, and she refuses to go away. This and the repressive environment, which she wants to adjust to but can't, cause Alina to freak out and she begins having fits of violence and anger. A trip to the hospital under restraints helps temporarily, but back with the nuns she soon has a fit again. Perhaps she is insane; but fundamentalist Christianity seems unable, officially anyway, to adjust to the idea of mental problems, and the priest, followed by his obedient flock of nuns, chooses to start saying the girl is possessed by Satan.

Mungiu himself is saying two things here, interpreting the actual events. First, contemporary Christianity in this strict Orthodox form provides ritual and belief and a long list of potential sins, but doesn't lead people to be kind to one another. Second, in a lastingly traumatized post-Soviet Eastern Europe too society is numbed and people are poor responders to personal human emergencies.

In describing its events the film seems to me much too drawn out and repetitious. The long handheld takes shot by Oleg Mutu are fine, their muted colors and dark shadows dramatized by the snowy exteriors of a severe winter, but there needs to be fewer of these takes. (Mungiu says that there was another half hour that he cut out with difficulty.) On the other hand, the acting and staging and writing are certainly good. One could just say this is Bressonian and leave it at that. A Man Escaped and Diary of a Country Priest are repetitious too. But they are Bresson, which Mungiu isn't. There is a drab ordinariness that gets in the way of the spiritual in a Romanian film. Mungius lacks a sense of the spiritual. Despite an effort at evenhandedness and avoidance of pointing blame, it is hard to appreciate that these nuns and their priest have any kind of spiritual life. We don't get any sense of the place's rituals or of the symmetry and peace they might bring. There aren't even scenes of group prayer or music. And though he may not be demonized, neither is the priest (Valeriu Andriuta) ever given a charismatic moment. Nor are the nuns indiidualized as the monks obviously were in Xavier Beauvois' 2010 Cannes Grand Prize winner, Of God and Men. So for all the 150 minutes and the self-consciously neutral, realistic approach, there's a lot left out of the picture.

I can't deny that Beyond the Hills is compulsively watchable. But despite showing the distressing downward spiral of a young woman who winds up literally chained to a wooden cross, it's more predictable than and not as emotionally disturbing and intense as Mungiu's previous 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007), which won the Golden Palm at Cannes, putting him and Romanian cinema in general decisively on the international map.

Dupa dealuri (the original title) debuted at Cannes, where it won Best Actress (jointly for Stratan and Flutur) and Best Screenplay awards. Also shown at Toronto and Hamburg. French release secheduled for November 21, 2012. Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-22-2012 at 02:20 PM.

-

Jun Lana: BWAKAW (2012)

JUN LANA: BWAKAW (2012)

ARMIDA SIGUION REYNA AND EDDIE GARCIA IN BWAKAW

Man, dog, and closet

An aging, long-in-the-closet gay man, a no-go love affair, and a dying dog make this touching film with veteran star Eddie Garcia whom director Lana has described as "the Clint Eastwood of the Philippines." Let's imagine for a minute Clint actually playing this role. It ain't happening. Let's also look at Mike D'Angelo's Toronto tweet review (I do not hide my admiration for D'Angelo's terse Twitter coverage). He gives it a 56, a creditable but not great score in his system, and says, "Bit of pathos overload—lonely aging gay protag coping with unrequited love and a dying dog. Honest & direct, which helps." What's admirable about Bwakaw is its peaceful, rambling accumulation of narrative details that also gradually build up a sense of slowly earned caring for Rene (Garcia) -- the character based on a real person the writer-director knew. And because Rene is a chilly, grumpy, downright hostile type, sentimentality is safely tamped down, despite the inevitable "pathos overload" of the story content.

In a post-screening discussion there was mention of Umberto D. I was reminded a little of the Roman screenwriter Gianni Di Gregorio's 2008 directorial debut Mid-August Lunch, which though distinctly different, seems a more interesting comparison. Di Gregorio's world is glossy, Mediterranean, and very Italian. His alter ego, Gianni, is not gay, and his mother is not dead. But he lives with her as Rene did with his. He like Rene he is essentially alone and has nothing to do. Rene's world is more primitive and Third World. But perhaps because of that, life pushes its way in a bit more, particularly in the person of Sol (Rez Cortez), the rough, gangsterish tricycle cab driver whom Rene at first hates, then bonds with, then hopelessly loves.

Rene by his own "honest & direct" declaration to his priest (whom he "confesses" to only to revise his will) has been a lifelong "coward." He strung along Alicia (Armida Siguion Reyna) for fifteen years pretending to love her as she loved him. Now he visits her at a retirement home, where she can't remember him, till in a moment of clarity she does and he can ask her forgiveness. It took him well into old age to own up to his homosexuality. And when he tries to kiss a sleeping Sol after they've gotten drunk together, it's to "see what it feels like." He's never even kissed a man. But the "pathos" of this avoids "overload" (at least fitfully, throughout) through humor, some of it macabre, like the coffin Rene has bought in a "summer sale' and must take possession of when the funeral home goes out of business. He tries it out at home and finds it more comfortable than he'd expected. Later to avoid a friend's (comically) twisted face in death he practices a fixed smile while laid out in faux-death. A folk religious note comes through a Jesus figurine his mother slept beside all her life, which is reputed to have healing powers. His hairdresser friends Zaldy (Soxie Topacio) and Tracy (Joey Paras) add a trashily camp gay note. Due presumably to his sudden interest in Sol, Rene yields to their dubious suggestion and gets a dye job that makes him look like an even prunier-faced Ronald Reagan.

The dog, Bwakaw, is a stray in the neighborhood Rene fed and semi-adopted, but never showed affection for. And like Uggie, the dog in Michel Hazanavicius' The Artist, Princess, the accomplished trained acting canine in this movie, becomes the co-protagonist. When she becomes ill she turns into Rene's main preoccupation, the Muguffin if you will that teaches him to feel and by releasing sadness enables him to embrace life again. He unwraps all the objects in the house he'd packed away after his mother's death and labeled for his handful of chosen "heirs," the gay hairdressers and coworkers at the post office, where he's been showing up every day to do chores even though he's retired, just to have something to do. The house looks radiant and Rene walks off into a lush winding forest road, shot from above.

Bwakaw is a little long (at 110 min.) and definitely episodic and its protagonist is slow to grow on you, but ultimately this is a movie that can appeal even to the hard-hearted, except that it sometimes doesn't, due to the off-putting title and the bleak plotline. In addition, thanks perhaps to the hurried shoot imposed by a low budget, there are some wrong notes. After the still quite young Bwawkaw has gotten sick and been diagnosed with cancer, she still seems awfully perky at times. (In truth simulating cancer may be too great a challenge for even the most talented canine.) When Minda (Luz Valdez), the post office friend, becomes ill, Rene steps out of his dour character a bit too much in giving her a pre-op party. Surely Rene's frequent visits to the handsome young priest Father Eddie (Gardo Versoza) reflect an attraction, but that's an aspect that's fudged on screen. The alterations in Rene's mood are a bit on the crude and abrupt side, the film's fault, not Eddie Garcia's. And despite the sociability of Filipino culture we don't feel a social context here as we do in the Italian films I've mentioned. But Bwakaw is a respectable and original effort. Rene is a genuinely memorable character, both unique and expressive of something basic in the human condition, that we are all alone, and we all must die.

Bwakaw debuted at the Cinemalaya Philippine Independent film festival in July 2012 and was also shown at Toronto in September; and at the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center a month later. Screened for this review as part of the NYFF. It has been chosen to be the official entry of the Philippines to the Best Foreign Language Film competition at the 85th Academy Awards 2013. In a Skype Q&A director Lana reported the local release was brief but lucrative enough to break even on expenses. He also mentioned that Eddie Garcia very willingly took on the role, and that Princess has her own TV series and besides that is trained as a bomb-sniffing dog.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-24-2012 at 08:02 PM.

-

Valaeria Sarmiento: LINES OF WELLINGTON (2012)

VALERIA SARMIENTO: LINES OF WELLINGTON (2012)

Napoleon's forces chaotically routed in Portugal

Described as "An epic set in and around the Battle of Bussaco (1810)" and designed as a TV mini-series, this handsome-looking 151-minute costume piece, which has nice crowd scenes, is a meandering and episodic war story that recreates the chaos of Tolstoy's Battle of Waterloo without the grandeur and ultimate sense. There are many mini-plots, none of which catch lasting emotional hold. The film represents a project begun by the lat Raúl Ruíz, completed by his widow, Valeria Sarmiento. A cast almost absurdly rich in well-known names includes John Malkovich (as Wellington), Catherine Deneuve, Isabelle Huppert, Mathieu Amalric, Vincent Pérez, Marisa Paredes, Chiara Mastroianni, Melvil Poupaud, Michel Piccoli, Elsa Zylberstein, Christian Vadim. Vincent Lindon, and Malik Zidi. Malkovich is ageeably diseagreable as usual, and Amalric does a voice-over in French, but most of the others just appear in brief 'wow" cameos. Despite big festival showings (Venice, Toronto, New York) and a theatrical release, this isn't a film that has box office potential and may function best as a rainy day soporific.

There is barely any one thread (other than the fact of the war going on) that links the whole rambling thing together, or makes us care, and that includes the fortifications referred to as the Lines of Wellington. The atmosphere, and the historical events referred to, would be of special interest to Portuguese viewers, though as in Ruíz's previous work the confounding but rich Mysteries of Lisbon, there is dialogue in English, French, and Portuguese.

Jay Wsissberg sums things up in his Variety review thus: "Expectations were high, given Ruiz's pre-production input and the participation of "Mysteries of Lisbon" scripter Carlos Saboga, along with d.p. Andre Szankowski, but alas, "Wellington" is stringy beef. Aiming for a Tolstoyan vibe that personalizes history's great events, the pic is big, but not big enough; historical, but not exactly accurate; and the extra stuffing, which made "Mysteries" a treasure box of discoveries, here feels merely undigested."

Telling a story of masses of man and large events while focusing on the ordinary folk and still including scenes of major figures is a tricky balancing act, and this film does not perform it successfully, seeming indeed indifferent to the need for subordination and clear guidelines.

A wounded lieutenant, Pedro de Alencar (Carloto Cotta) is the closest thing to a linking figure. He appears repeatedly, first wounded on the battlefield, then in hospital, later escaping in hospital gown to be protected by an older lady, finally, recovered serving in a motley unit till he rejoins the platoon he commanded originally.

But if this is a "miniseries," maybe it was cut, and cut badly. The original intentions of Carlos Saboga may have been lost -- or never defined. An unfortunate aspect, for following the action in a feature film format, is the lack of intertitles and the frequency in which characters occur who speak both Portuguese and English and are of mixed origin. With a chaotic palette it would have helped to draw the lines carefully and clearly. It's not that difficult; but it's not that easy, either.

What we learn at the outset is that the Portuguese allied with the English are the local victors, but have to withdfaw because the French still outnumber them. The finale leaves us with a vague sense of victory for the Portuguese-British side, but without anything to rejoice over. The final text describes the country as ravaged for years to come by this warfare.

As Weissberg says, if you loved Mysteries of Lisbon (which does have its enchantments despite its being harder to follow) there may be some carry-over to liking Lines of Wellington. But not much, really.

Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-10-2012 at 04:56 AM.

-

Song Fang: MEMORIES LOOK AT ME (2012)

YE YU-ZHU, SONG FANG IN MEMORIES LOOK AT ME

The mundanity of it all

In Oliver Glodsmith's 1760-61 pseudo-Chinese letters called The Citizen of the World, there's a moment when an Englishman expresses disappointment at the Asian visitor's talk. He'd been expecting exoticism and arcane wisdom, and all he is hearing, he says, is "mere chit-chat and common sense." That is the shortcoming of this new prizewinning feature from Song Fang. It is a cozy in-family celebration of Chinese matter-of-fact-ness so unwavering as to be numbing. There are fundamental truths about life here, but they are buried in the non-drama. As the Hollywood Reporter reviewer Stephen Dalton put it, only the "most serious art-house cinema" audience will warm to Song's "narrow focus and chilly film-school minimalism."

The young female director had full cooperation from her mother and father and other family members in shooting this docu-drama in which she comes for a visit and talks at length with her parents and particularly her mother about aging, her grandmother's death, and other day-to-day issues. The focus is on aging and on how memories link family members. There are links with the documentary fiction of the film's producer Jia Zhangke and also of the low keyed focus of Hou Hsiao-hsien. Song starred in Hou's Parisian-set Flight of the Red Balloon (NYFF 2007). Song's delicacy and the clean lines of her editing and cinematography (rudimentary equipment doesn't keep there from being some beautiful, simple images), plus the focus on humanistic concerns that are universal, won her the Best First Feature prize at Locarno.

However, a scene in whch Song's mom takes her dad's blood pressure and finds it at an all-time low provides a metaphor for the whole film: the claustrophobic indoor "action," which consists of sitting around and talking, is so delicate and matter-of fact that it will lower your blood pressure, and maybe even put you to sleep. How much do you really care when Song first went to middle school, or why she thought her mom looked older than other moms then? As the chit-chat and common sense spill calmly out of mouths, the humanism becomes hard to discern from the mundane detail, and Song's film does not sing. However, the film has a simplicity, purity, and natural flow that make one understand the Locarno jury's admiration. But then I think of Edward Yang's Yi Yi and this dwindles to a tiny scribble. Rigorous this may be, and economical it certainly is, but it also seems lazy, hugely unadventurous, and numbingly lacking in cinematic verve.

The transliterated Chinese title of Memories Look at Me is Ji Yi Wang Zhe Wo.

Screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-11-2020 at 08:25 AM.

-

Paolo and Vittorio Taviani: CAESAR MUST DIE (2012)

PAOLO AND VITTORIO TAVIANI: CAESAR MUST DIE (2012)

GIOVANNI ARCURI AS CAESAR IN CAESAR MUST DIE

Shakespeare in a Roman prison

The prolific Taviani brothers (of Padre, Padrone and Night of the Shooting Stars) focus on the theme of a prison theatrical production in this emotionally strong documentary that focuses on rehearsals, the performance, and the cast's return to their cells in the maximum security section of Rome's Rebibbia prison in Cesare deve morire/Caesar Must Die, winner of the Golden Bear at Berlin and a lot of prizes and nominations in Italy. Unfortunately in the effort to make a polished and performance-like film, certain details have been fudged and when the thrill has passed, the whole thing feels a little less profound and informative than it might have been. Details of the production, such as the fact that the director, Fabio Cavalli, has put on plays at Rebibbia for years and built up a semi-pro cast among the inmates, and how the final performance was actually staged, are left unexplained, and worst of all, every shot, even where the actors have conflicts, rebel, or speak personal asides, seem so obviously pre-rehearsed that one feels robbed of true insight into what went on.

We begin with an overview of what appear to be auditions, in which prisoners are asked to say their basic coordinates -- name, home town, address, and some throw in a lot more -- in two moods: one as if they are leaving their family, and the other as if they have been delayed by the bureaucracy and are angry. So, sad and angry. And from here on, one is gripped by the macho theatricality of the inmates, all of whom come up with strong emotion and some of whom are astonishingly inventive. Next we see a group called out who have been selected as the cast for a proeduction in Italian of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, which they are directed to perform in their own native dialects. The majority identify themselves as Neapolitan or Sicilian, though one says he has no dialect and just speaks Italian. Subtitles for the main cast members give their part and their sentence and the crimes for which they have been convicted -- drug trafficking, murder, organized crime activities -- for which some have already served many years and all will serve many.

Next the film shows the actors memorizing their lines and acting them out among themselves. The opening and closing segments are in color; all the rest, the shots in cells and in hallways and of rehearsals, is in strong, effective black and white (in contrast to the flat B&W digital transfer from color of Noah Baumbach's Frances Ha, also a part of the New York Film Festival). These guys are good, in the sense that they project well, speak clearly, summon up wellsprings of appropriate emotion, and have dramatic flair. On the other hand one may question whether some of them have the right faces to represent the Roman aristocracy. The use of dialects has an obvious value: the actors may thus speak their lines as home truths, the better to identify the betrayals, loss of freedom, resentments, and plotting with their own combined memory of present and pre-jail experiences. Moreover in a Q&A with the directors after this screening, they explained that each actor translated his own lines from standard Italian into his individual dialect, providing them with an intellectually stimulating activity that may bring out an urge to write. On the other hand, the various dialects can be distracting and would break up the unity of the original Shakespearean text. All of which reminds us that this is a novelty and a feat and not a work of art for general consumption, however fascinating it is to study jail performances, as we know from Beckett in prison decades ago.

Rehearsals -- with the mood flare-ups that seem artificial -- blend seamlessly into performance. But here is another place where the Tavianis have fudged and distorted. While it's obvious from the opening and closing sequences that the play was performed on a stage surrounded by large columns before an audience who came in from outside, in the film sequences are staged in hallways and a courtyard of the prison. As Jay Weissberg rightly points out in his Berlin review for Variety, these sequences staged by the directors only for the film distort the desired sense that this is a prison, that the inmates live constantly in small cells, and that they're only "free" in the director's rehearsal space and the final on-stage performance. In this misleading context, as Weissberg says, a shot of part of the play artificially set up with the sky all around above (as it never can be in Rebibbia) "turns the cells into a theatrical construct" when the prisoners are shown being let into them one by one in a sequence that bookends the film.

It's a shame that in the interests of evaluating the film fully as documentary material, one must focus so much on these various elisions and distortions. Caesar Must Die remains a theatrical-cinematic artifact of strong interest that can't fail to move you at certain points when you watch the inmate-actors in action and their skill and their ability to harness "emotional memory" in the Strasberg sense. The language may not mesh and the faces may not always be right, but the energy and fluency of the performances of everyone in the cast are impressive. (It would have been nice to see more instances where someone fumbled or forgot lines or got pointers from the director.) I have to point out another significant tweaking of the situation not acknowledged in the body of the film: the actor who plays Brutus, Salvatore Striano, was released six years ago and brought back to act in the production.

According to those credits the impressive and well-cast Giovanni Arcuri, who plays Caesar, has written a book about "freedom in prison," and the theme of inner vs. outer freedom is one the filmmakers seek to develop, though it would come through much better had they delved more deeply into the details of the play production process and been willing to move back and forth from slick performance to awkward reality. Instead it's all slick performance, even the ostensible off-text scenes.

Weissberg points out that sometimes to the "sharp-eared" or keenly observant the dialects and the prisoners' mafia connections give certain spoken lines an inappropriate or comic overtone, and he notes "distracting post-production dubbing" audible in the alteration of some speeches. On the other hand the fact that some of these men are murderers and have a violent past gives stabbing scenes a chilling double reality. The surging music by Vittorio's son Giuliano Taviani is sometimes derivative or repetitions, but has a generally strong unifying effect, underlining the throbbing emotion and adding to the distinctive look and feel of the film.

Cesare deve moriere debuted at Berlin, as mentioned, where it received the Silver Bear award. It was screened for this review as part of the 20012 New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, where it is showing Sept. 29 and 30 and Oct. 1 and 8. It already has been or soon will be released in over a dozen countries; no US distributor yet (as of Sept 27, 2012).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-10-2021 at 11:48 PM.

-

Raul Ruíz: NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET (2012)

RAUL RUÍZ: NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET (2012)

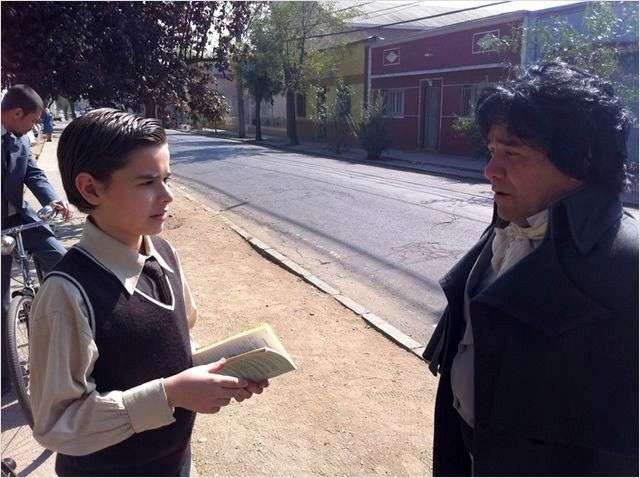

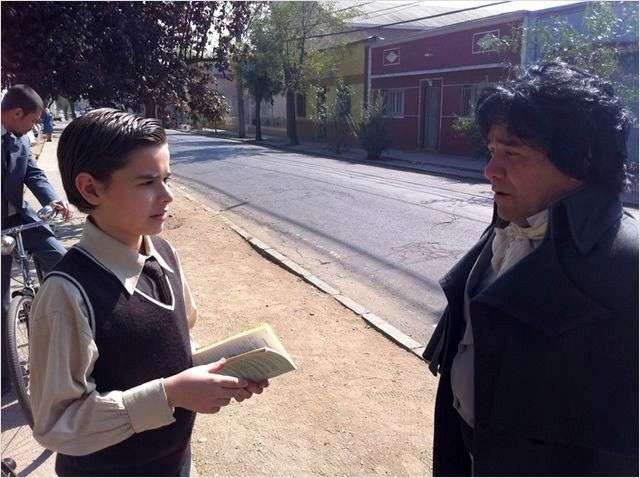

SANTIAGO FIGUEROA AND SERGIO SCHMIED IN NIGHT ACROSS THE STREET

A summation with a light touch

Raúl Ruiz is the Chilean auteur known for Time Regained (a symphonic riff on Proust) and his lush recent miniseries Mysteries of Lisbon (but director of more than 100 films if we include shorts and documentaries). Though he lived in exile ever since the dictator Pinochet came into power in 1973, he was reportedly greeted affectionately on the street in Chile as "Don Raulito." He died in France last year, shortly after his seventieth birthday, after a serious illness that had been temporarily reversed by a liber transplant, and after a celebrity funeral in Paris his body was returned home and a day of national mourning was declared. La noce de enfrente/Le nuit d'en face/Night Across the Street is an intentionally posthumous cinematic last testament. Ruiz told the younger crew members on the rapid shoot that it was his last film, but concealed this from friends and family and producer (and friend) François Margolin. The title could be translated as "the coming night" -- as it is at a key point in the film's English subtitles -- and thus mean the oncoming darkness, the approach of death. Conversely it's already being celebrated for its youthfulness, for being more like a first film than a final one. Indeed it is a lighthearted, amusing, playful and surreal film that slides around in time with a freedom that may baffle the first-timer. For that matter it may not be too clear on the fifth or sixth viewing -- if you haven't done your homework in between. This is a film for Ruiz aficionados and selected festival-goers.

But it's not like the film itself is a total, baffling mystery. Ruiz himself provides an excellent Night Across the Street for Dummies in the form of a brief Cannes Statement about the film. His starting point, he explains, is the Chilean writer Hernán del Solar (1900-1985), one of a group of Imagists who went against the naturalism that grew up in the Forties and Fifties. "In Del Solar's works," Ruiz writes, "daily life coexists with the dream world, with tenderness and cruelty, the literary evocations and the omnipresence of the universe of childhood." That tells you also what to expect in his film. Two of Del Solar's stories, Ruiz also tells us, are "Wooden Leg" and "The Night Across the Street." "Wooden Leg" is derived from Long John Silver of R.L. Stevenson's Treasure Island, of which Ruiz, whose father was a ship captain and who had a lifelong fascination with pirates, had done a screen adaptation. He's a character in the film, this Wooden Leg (Pedro Villagra) , and so is Beethoven (Sergio Schmied), or a Chilean child's imagined version of the German composer.

The film begins with an engaging scene of one Don Celso (Sergio Hernandez) sitting in a class taught by the writer Jean Giono (Christian Vadim), a provincial Frenchman whose daughter Ruiz, he tells us in his statement, once met. She told him how Giono, who feared even going to Paris, once announced to his family that he was going to move to Antofagasta, a port in the north of Chile, which he picked solely because he liked the name. In the film he is there, teching a class in French literature in which he asks students to close their eyes and meditate on his words.

The story of the film, Ruiz tells us in his statement, takes place in Antofagista in the present time, and there are modern buildings, as well as ones from the past; but the characters don't see the modern ones. The film, we could say, creates a limbo between past and present, real and fantasy, and lingers there, ready to shift back and forth at a moments notice.

Starting with the poetic classroom of Jean Giono, the film plays with various verbal motifs, particularly recurring to the word "rhododendron." The little boy in the story, the young Celso (Santiago Figueroa), is sometimes known as "Rodo." The old Don Celso works in an office and is about to retire; but the film often shows him in his imaginative boyhood, when he has conversations with Beethoven and Wooden Leg. Following what he considers an Imagist stye worthy of Hernán del Solar, Ruiz imagines the mature Don Celso likewise having conversations with Jean Giono, even though Giono is also a writer working in France. And Don Celso is also in a rooming house, where he expects someone is going to come and kill him. As Ruiz puts it, "the horror of an impending crime grows in importance." He also says this is "a weaving narrative, only half explicit, and a dark story of crime and treason."

This threatening plot element serves as a thread pointing toward a definite finale (the "coming night") and thus offsets the playful shifting back and forth between present and past, reality and fantasy, of the film's minute-to-minute texture. It's a Whodunit! Or almost. Several pistols are introduced, and they have to be used, except that we don't ever literally see them used; we only view corpses, and figures with red bullet wounds, who are alive. In the context of this film "Imagist" evidently means "surreal," and the mindset of Ruiz's film is certainly more surrealist than super realist. The ghost of Jorge Luis Borges (perhaps due to the affection for Stevenson) seems to hover somewhere, even though Borges was from Argentina and not Chile. Borges' dates are very close to Del Solars, 1899-1986.

Ruiz ends his film statement with a funny mistake -- confusing two utterly different modern artists. The "possible world" of Giono in Antofagasta that threads through Night Across the Street contrasts with the "real" world of the modern town that the characters "ignore and refuse." He says this is like the painting "of Matisse" that shows a pipe with underneath it the legent, "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe"). He meant Magritte, of course. But who knows: perhaps in this kind of auteurist cinematic world, "Ceci N'Est Pas Une Pipe" was painted by Matisse!

Justin Chang's Cannes review for Variety has a fine description of the film's modality. Mentioning the director's "smoothly panning camera movements and ingenious sense of staging" he goes on to say, "Ruiz has a way of positioning the protagonist both within and outside his own recollections, as though observing and participating at the same time. The director's frequent use of doorways and mirrors to frame and isolate his characters suggests many layers of (un)reality nestled within this curious dreamscape, whose transparent artifice is underscored by the film's intense level of stylization, especially apparent in the gold-burnished tones of d.p. Inti Briones' HD lensing." Prepare not only for a head trip but a sweet and dreamy visual experience, which may remind you of recent films by the now 103-year-old Manoel de Oliveira.

Night Across the Street is the quintessential justifiable festival film, much more so than the mainstream release titles, Story of Pi, Flight, and Hyde Park on Hudson, shamelessly included in the Main Slate of this supposedly "elite" and "highly selective" festival to sell tickets, not to mention arty but drab and uninspired titles like Memories Look at Me, Araf, or Here and There.. Richard Peña, the director of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, has said that the New York Film Festival has chosen Ruiz films to be in the elite selection of its Main Slate, but never just any Ruiz film. This is hardly any Ruiz film, because though it may be hermetic and obscure it is also beautiful -- its delicate images in a lovely haze created by the yellow filter -- and as the final work of the great exiled Latin American auteur, it deserves a very special place. I didn't really very much enjoy watching it but I enjoy thinking about it, and I would probably enjoy watching it again.

La noche de enfrente debuted in Cannes' Director's Fortnight in May and has continued to a number of festivals including Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver and New York. Watched at the NYFF press screenings for this review. It also opened in Paris in July receiving critical raves (Allocné 4.1).

FRENCH FILM POSTER

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-28-2012 at 08:29 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks