-

Frederick Wiseman: AT BERKELEY (2013)

FREDERICK WISEMAN: AT BERKELEY (2013)

From At Berkeley

Wiseman provides a reassuring picture of today's UC Berkeley

The seemingly indefatigable American independent documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman, still productive at 83, has made a four-hour study of the University of California at Berkeley, so famous for its Free Speech Movement and its role in the anti-Vietnam War movement in the Sixties and early Seventies, as it is today. The theme that emerges is of a struggle, apparently so far successful, to remain a world-class place of learning in the face of post Great Recession budgetary restraints, cutting corners while trying to maintain the quality of teaching and research. There's no big news here. But Wiseman, editing down over 128 hours of digital footage, provides one of his best recent portraits of an institution, shifting around from classroom teaching to meetings of various administrators, in which the Canadian-born Robert J. Birgeneau, 2004-2013 chancellor and a renowned MIT physicist, features prominently.

Nothing is happening. And then something quietly is. A student protest, mainly calling for a return to free tuition, begins with resounding speeches on the Sproul Hall steps that invoke Mario Savio of the FSM and moves on to an occupation of the Dow Library reading room. This is an event that earlier we see being in general terms planned for at a discussion of campus cops and administrators. In the event, it disperses quietly, only to be quietly mocked later by Birgerneau at yet another administrative meeting for its lack of a forceful, specific goal -- the usual criticism of the Occupy movement.

Tellingly, perhaps (and one can always argue that Wiseman's "fly on the wall" coolness is undercut by his pointed, sometimes metaphorical, editing) there's a class in which the lively Chancellor's Professor of Public Policy and former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich talks to a mini-arena about the difficulty administrators or leaders have in "self-evaluation" since they can't get constructive criticism from their staffs even when they want it. Threaded through are sequences in classrooms. In one students discuss the growing economic squeeze on the middle class and its effect on students at UC Berkeley. At another meeting, not a class, scholarship students feeling the pinch are counseled to suck it up. There are also professors analyzing Walden and a poem by Donne, or talking about neuro-science, physics, or paleontology. In between are cool wide-angle shots of the university's buildings, in a bland style that seems to combine Spanish mission with Stalinist. An occasional shot shows a chorus of busty sorority girls singing out of doors, a skateboard or two zipping by, students studying on the lawn or crowding through the plaza.

Wiseman seems to have had remarkable access, to all academic meetings except those on tenure, and to a variety of classes. We don't see anything lively, exciting, or brilliant happening in a classroom. Nor do we enter a dorm or see students working out at the gym, sitting in a dining hall, hanging out, or drinking beer. A decision was made to exclude footage of the city of Berkeley. The filmmaker gives us some kind of Platonic ideal of a serious, academically superior American university (Berkeley being traditionally the most elite of the many UC campuses for undergraduates, the most richly supplied with Nobel Prize winners). The result is reassuring but also a little numbing.

Happily, perhaps, this is all in sharp contrast to the lengthy 1994 PBS Frontline documentary "School Colors," which depicted the volatile mix of violence, racial conflict, idealism and talent then prevailing at Berkeley High School. That documentary, based on a year of shooting, showed the ideal of school integration failing. In contrast black students at UC Berkeley in Wiseman's film, gathered with Asian and white students to discuss issues of race and education, express satisfaction that at the university they're no longer stared at when they speak in class or stereotyped as unintelligent as they were in high school. In a way the lack of drama at Wiseman's Berkeley is reassuring. But the financial crunch remains a threat to the school's excellence. How long can a great public university keep raising student fees and still call itself public?

At Berkeley, 244 mins., debuted at Venice, was shown at Toronto, and was screened for this review as part of the 2013 New York Film Festival. It reportedly will later have a theatrical run in NYC at IFC Center and Lincoln Center. It airs on PBS starting Monday, January 13, 2014.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:08 PM.

-

Hirakazu Koreeda: LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON (2013)

HIRAKAZU KOREEDA: LIKE FATHER, LIKE SON (2013)

An old theme deliberately muddled?

Koreeda, who has dealt with children being separated from parents before, turns this time to the old theme of babies switched at birth. And he does not avoid the cliché of contrasting social levels. This isn't exactly a prince and a pauper, but two of the parents are ambitious and moneyed, and the others are humble. Along with that comes the obvious association of the wealthy with coldness and distance and the poor with more humanity. Perhaps Koreeda's greatest strength here is a weakness: he takes forever to resolve things. Neither the emotional decision about how to resolve the discovered child switch nor the question of nature vs. nurture is ever satisfactorily concluded, and this uncertainty makes for an emotionally complex and thought-provoking, if still somehow somewhat weak film. Certainly this is also a take on the theme that's both contemporary and Japanese. And to add a touch of class, Koreeda's low-keyed treatment has its main sequences delicately linked with the opening passage from the Goldberg Variations.

Though the poor family is somewhat romanticized, the wealthy one gets more attention. Right off the focus is on the ambitious corporate architect Ryota Nonomiya (Masaharu Fukuyama) and his wife Midori (Machiko Ono), who live in a posh glass and steel apartment and are pushing their six-year-old son Keita (Keita Nonomiya) into a fancy school. Well, they think he's their son. Poor Keita is like a little doll, and his handsome father is distant and withholding toward him (and also somewhat toward his wife), forcing the boy to take piano lessons, though he isn't very good, obsessed with money and success. The main focus remains on this family. Later when the hospital contacts them about the discovered switched babies, we meet mom Yukai Saiki (Yoko Maki) and dad Yudai Saiki (Lily Franky). He has an appliance repair shop in a not-very-attractive neighborhood. Their son is Ryusei ( Hwang Sho-gen) -- or so they thought. They also have a couple of other kids.

Because Koreeda's solution is to tease and twist his theme rather than resolve it, the film forces the viewer to linger over how wrenching and confusing it would be both for adult and child to learn parents have been raising and loving the wrong kid. But either the discomfort is most felt by the architect Ryota and his wife, or we just don't get to see how the Saikis experience it. Despite Ryota's disdain for the other parents and their lifestyle, he arranges for the two families to start meeting and socializing, and having Keita and Ryusei switch places on a temporary basis, which Ryota tells Keita is a "mission" (using the English word), to "toughen" him.

Keita is won over by Yuda's ability to fix anything, including mechanical robot-monsters, and by his general playfulness; the boy also seems to like the togetherness of bathing with the poor family in their tiny bathtub. On the other hand, Ryusei enjoys the luxury of the architect's house. However, for the Nonomiyas, all is inner turmoil. She misses Keita terribly; he knows that his withholding nature isn't going to win Ryosei's affection. Meanwhile there is much discussion of a damage suit against the hospital, and an irrelevant subplot about a nurse who makes a confession. Meanwhile Ryota tries at first to pay off the Saikis and gain the right to raise both Keita and Ryusei, thus resolving any abandonment guilt and still gaining control of his blood offspring. But this is immediately rejected, and Ryuta simply starts believing his father's advice that the genetic link will come through in the end.

At times it seems that nothing is really happening. In contrast to traditional rags-to-riches or prince-and-pauper tales, Koreeda's provides no dramatic incidents. He works with a series of small, delicate ones designed to bring out social and cultural differences and spotlight little emotional shifts. He also shows how quickly the boys, like most children, can adjust to changed circumstances. Meanwhile complexities in Ryota's background are added on top of his initial impression of mere chilly ambition, and the way is paved for a moral transformation that might be corny if it were not undercut by a deliberately ambiguous finale. Thus Koreeda underlines the point that to the question of who is the true parent, the blood one or the one who has raised the child, there is really no final answer.

There are three Koreeda films about children now, the 2004 Nobody Knows, the 2011 I Wish (FCS 2012) and now this. While I Wish had charm, magic, and much more intimate focus on children, Like Father, Like Son is more troubling and complex. But neither can begin to compare with the devastating true tale Koreeda tells about the children abandoned by their irresponsible mother in Nobody Knows, which takes us into the heartbreaking, yet resilient world of children left by themselves and, afraid of being put into foster care, desperately pretending to the outside world that everything is fine. There is nothing like having a truly meaty theme to deal with. The other two films feel contrived in comparison. While it may be that as Derek Elley says Koreeda's films tend to be half an hour too long due to his insisting on doing his own editing, in the case of Nobody Knows that extra time contributes to our sense of the length of the children's ordeal; in the other two, it just seems like meandering.

Like Father, Like Son, 120 mins., debuted at Cannes and was shown at over a dozen other international festivals before being screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival. NYFF public screenings: MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 6:00 pm, Alice Tully Hall; WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 6:00 pm, Francesca Beale Theater.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:10 PM.

-

James Franco: CHILD OF GODJ (2013)

JAMES FRANCO: CHILD OF GOD (2013)

Scott Haze in Child of God

James Franco does Cormac McCarthy, literally, with feeling

The prolific James Franco may have arrived as a feature film director when his adaptation of William Faulkner's As I Lay Dying became an Official Selection at the 2013 Cannes festival and got US theatrical release for this September 27th. He also has an adaptation with Vince Jolivette of Cormac McCarthy's Child of God. This (which may also be said of Faulkner's novel) is a book whose prose is unique, and to turn it into moving pictures is to rob it of what makes it a work of art. You can say this about any novel-into-film, but it's more true of some than others. Child of God is one of McCarthy's early, deep-South books and it concerns a disturbing and repugnant character (not that McCarthy's books are not rife with malignant and horrific people and acts). The Tennessee novels' effect is disturbing however you approach them but they are meant to come drenched in the authorial voice and its special way of evoking a period and milieu that at the same time is really McCarthy's world, and no place else; his sensibility, and no one else's. Franco's version is a well-made film, dominated by a once-in-a-lifetime, balls-out performance by Scott Haze as Lester Ballard, the crazed outcast, the titular, protagonist "child of God" (testing the range of that concept) who in the course of the story becomes a cave-dweller, murderer, and necrophiliac. This version is also too literal, following the narrative structure and four parts of the novel closely rather than re-imagining it. Franco needs to take on more filmable books, or to film a story of his own devising.

You have to credit Haze, Franco, and the other cast and crew members, who shot in West Virginia rather than the novel's Tennessee, for recreating very vividly a challenging series of events. Some of the encounters with a mean southern cracker sheriff, ably played by Tim Blake Nelson, even some of Lester's earlier running around and rough encounters with locals, are familiar stuff. But we've never seen a wild man find a young couple suicided in the back of a shiny Forties Pontiac and then copulate with the girl, and then lug her body to his cottage for further use. I won't forget Lester's struggle to carry the girl's body up a ladder to the loft of the cottage, or the cottage all in flames later when he accidentally sets fire to it on a cold night; or how he fills with bullets the heads of the giant stuffed pooh-bear and tiger he won at a carnival shooting gallery (a sequence Franco added); or his flight through a cave escaping from a lynch mob. These are good acting, good staging, and good storytelling. But a few voices reading narration and a few artificial large paragraphs from the book flashed on the screen do not make up for the absence of Cormac McCarthy's style, among the most unique and sonorous in contemporary American fiction.

Lester Ballard is an extreme character and Scott Haze delivers in kind. Franco's regular collaborator Christina Voros provides handsome muted cinematography, in which the protagonist's crazed mind and adrenalin-drenched experience are evoked through shaky camera and rapid, rough-edged editing. The banjo-dominated bluegrass-style arranged by Aaron Embry is a little conventional, but it neatly links the surreal and comic aspects of the story. This film is not for everyone, to put it mildly. But for those whom it may suit it is absorbing and watchable. Only you should go and read the book, and all Cormac McCarthy's books. He is one of the great ones (see Harold Bloom). . . and this is only a glorified Cliff Notes "Child of God" (which I find is how Variety describes Franco's As I Lay Dying). James Franco is an A+ student, who uses his power, cachet, and name to good effect and doesn't waste them on soft or easy projects. We look forward to seeing what he does when he graduates.

This is added to the list of Cormac McCarthy film adaptations, along with All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, and The Road. It's probably no coincidence that the one that works best, the Coens' No Country for Old Men, is based on the least brilliant and McCarthyian of the adapted novels. The Coens had never done a literary adaptation before, and they are the best writers in the group. Nabokov tried to do his own screen adaptation of his masterpiece, Lolita. It was not a success..

James Franco's Child of God, 104 mins., debuted at Venice, was shown at Toronto, and was screened for this review as part of the 51st New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:12 PM.

-

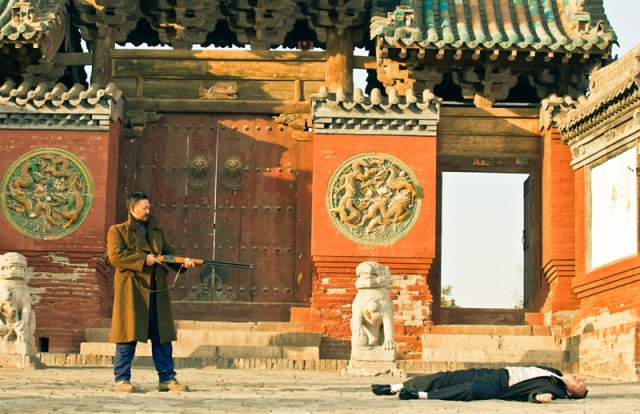

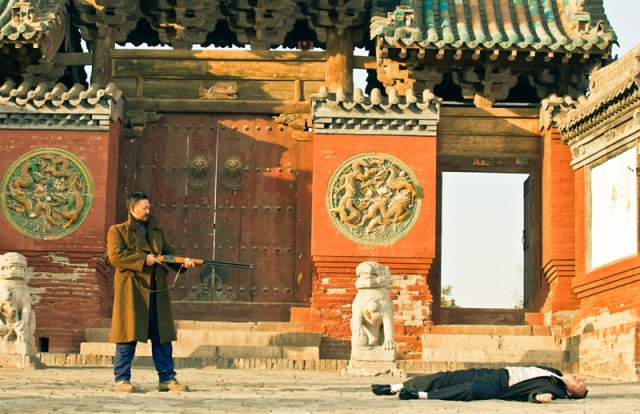

Jia Zhang-ke: A TOUCH OF SIN (2013)

JIA ZHANG-KE: A TOUCH OF SIN (2013)

Jiang We in A Touch of Sin

Jia takes a new genre tack, with mixed results

Jia Zhang-ke, China's most important unconventional "sixth-generation" movie director, has hitherto restricted himself to complex, generally low-keyed portraits of his country in the throes of development. But this time in A Touch of Sin he turns to a four-chapter study of violence that is both more overtly moralistic and more "genre" than anything he's done before. Obviously Jia has been jolted by what he's learned about the drastic ill effects and inequalities of rampant capitalism in the ROC. The panorama is rich, but the results are mixed and the collection lacks coherence. If his point is that bad behavior is rife, the point's well taken. But the kinds of "sin" are so various here that the effect is scattershot, the specific relevance to contemporary events unclear. However, the individual segments are still wonderful, at least intermittently, and the evocation of the contemporary Chinese milieu in various regions is often vivid. And some will argue this film is in harmony with Jia's other work: he has just added weapons and murder to make "a martial arts film for contemporary China," as film critic Marie-Pierre Duhamel quotes Jia as putting it. In fact, except for a highway sequence and a sauna killing sequence, this claim to having made a wuxia film is far-fetched indeed.

To begin with, there's an imbalance in the chapters. First comes a man who takes revenge on several political and social wrongdoers. Next is a guy who simply goes on a wild killing spree. Third is a woman who wrecks horrible vengeance on a man who mistreats her in a sauna-massage parlor. Finally we follow a youth whose aimless, impoverished life as a factory and sex worker and failed lover leads him to suicide. These can't be seen as at all the same kind of things, though all clearly do happen, though in different parts of the country, with similar backgrounds of rampant exploitation, graft, and inequality.

In the first episode Dahai (Jiang Wu) comes back to Black Gold Mountain, Shanxi province to blame the village boss in person for his personally profiting from selling off the state-owned local mine and not hsaring the proceeds with the workers as he'd promissed. Dahai writes a letter of protest about this to the Discipline Commission in Beijing but can't seem to get it sent. A new fat-cat mine boss Jiao Shengli arrives by newly acquired private plane from Hong Kong and at the ceremonial arrival Dahai confronts him and Jia Shengli has him brutally beaten with a shovel, which they joke is "playing golf." After visiting his elder sister, Dahai decides to take matters into his own hands and simply kills some of the wrongdoers. Dahai is an almost comically simple and brutal character, but his moral outrage is clear.

In part two, which is completely pointless and amoral, Zhou San (Wang Baoqiang), a migrant worker who loves guns, has already shot and killed three highway bandits from his motorcycle in the opening pre-title sequence in Shanxi (the director's home province). Zhou then visits his wife and young son in Chongqing, where his elder brother splits up the leftover money from their mother's 70th birthday celebrations. But he declines to take his share. Instead he goes on a trip that turns into a killing and robbery spree.

Part three. Further down the Yangtze River, in Yichang, Hubei province, Zheng Xiaoyu (Jia's chief actress and muse Zhao Tao) sees off her married lover, Zhang Youliang (Zhang Jiayi), on a train to Guangzhou, where he will manage a factory. He gives her six months to decide whether to join him or not. When she returns to work, she is later cursed and physically attacked her lover's angry wife. After visiting her mother out of town, Xiaoyu returns to the sauna where she uses a fruit knife she took from her lover when the train security people wouldn't allow it on a bullying customer who wants her to perform services that have nothing to do with her job as the cashier.

Next, in the fourth and last segment, In Guangdong province, at the factory managed by Zhang, Xiaoyu's lover, a young employee called Xiaohui (Luo Lanshan) is ordered to turn over his salary while a coworker is off work with an injury that happened while they were chatting. He instead runs off to Dongguan, where he gets a job in a luxury hotel that caters to rich sex tourists from Hong Kong and Taiwan. He bonds with a cute female coworker, Lianrong (Li Meng), who's from his home province of Hunan. The naive, pretty young man falls for Lianrong, but she tells him he knows nothing bout her: she has a 3-year-old child. When he sees her "working" at the hotel, his disenchantment causes him to flee again and go to work at another factory, where he soon commits suicide.

All this is interesting and illustrates Jia's penchant for rapid, disjointed incident and rambling storyline at a high level of energy, but it is also too much to take in. Derek Elley is doubtless right in his review of A Touch of Sin when he comments that Zhao Tao (but not the subtle Zhang Jiayi as her lover) is, as usual, a comely blank; hence I would say her murder, though revenge for criminal and odious behavior, seems cold and amoral. But as Elley says the young man's psychology in the last section is more fully developed. Though it's not made at all clear how he could suddenly have become desperate enough to kill himself, his naivety and disillusionment of his existence and his typical lack of anything but the grimmest prospects (much like the young men much earlier in Jia's Unknown Pleasures) come through clearly and movingly, even though they are subtle. For me, Still Life remains the most magical of Jia Zhang-ke's recent films, with unity and haunting delicacy.

There is much good stuff -- too much -- in A Touch of Sin. While the fourth, Xiaohui, episode is like a more touching segment of Jia's The World, one wishes that Jia had found a way either to expand the opening Dahai segment into a whole feature, or to have multiplied other segments in the same vein, perhaps focusing on other industries. While it's probably true as Elley says that "Most of Jia's films have been essentially episodic, with little grasp of long dramatic lines," in some of them that works more than in others. Platform, for instance, is held together by the adventures of the theater company, and becomes a rich chronicle of a decade. This time each episode is very strong in its way, but the whole suffers from the clear sense that they don't quite belong together. What is great in A Touch of Sin and makes it a delight to watch is the cinematography by d.p. Yu Lik-wai.

A Touch of Sin, 125 mins., debuted at Cannes May 2013, where it got the best screenplay award, and has shown since at half a dozen other festivals. It was screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center and is slated for a US theatrical release by Kino Lorber 4 October. My other Jia Zhang-ke reviews are linked here.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:15 PM.

-

Hong Sang-soo: NOBODY'S DAUGHTER HAEWON (20130

HONG SANG-SOO: NOBODY'S DAUGHTER HAEWON (2013)

Lee Seong-jun and Jeong Eun-chae in Nobody's Daughter Haewon

An auteurist Korean Woody Allen?

The blurb term "deceptively simple" indeed applies to this Hong Sang-soo iteration, in that very little seems to be going on -- but the end apparently is a dream, and that fooled me. And it also fooled my friend, who was delighted with the film, though unable (perhaps blissfully?) to remember any of the various other Hong films we've both seen before at Lincoln Center, which has presented six or seven of the Korean auteur's works at iterations of the New York Film Festival. I have enjoyed most of the others more, and therefore must side -- cautiously -- with those who consider this one a "tired retread" (Derek Elley), even though there are moments -- for some of us, anyway, such as my friend. I also agree with Mike D'Angelo in wondering if "the professor/director's (yes, again) obsession with that hideous techno rendition of Beethoven's 7th [is] meant to be funny, or weirdly poignant." What's clear is that it's hideous (he plays it on a cell phone). And why do some aspects of Hong's films, the camerawork, and the external shots, for instance, so often seem colorless and merely routine? The main characters are usually played by attractive people, with interesting or pretty faces and nice voices. The "professor/director" speaks in deep resonant tones.

This one has a twist: it has a girl at the center of it, and a very pretty one, who's "abandoned" by her mother, who goes to Canada to be with her brother. There's also a chance meeting with Jane Birkin, which brings out that the girl, Haewon (Jeong Eun-chae) speaks good English, and also wants to become a successful movie actress. Birkin says Haewon resembles her daughter, Charlotte Gainsbourg (she does; she's meant to) -- which delights Haewon. After a farewell (tea) drinking session with her mother, Haewon walks past the Jongho public library and sees the Famous Hotel, which has memories of her brief affair with Lee Seong-jun (Lee Seon-gyun), the director and also her current teacher. She calls him because she's lonely and they meet up and drink, joining other students and pretending that they met by chance. The theme of hiding, but not hiding, an affair is repeated with them and another couple.

A week later Haewon and Lee Seong-jun go to Namhan Fortress, in the hills south of Seoul, where they have a big argument over their affair. Lee is furious that Haewon has slept with a younger guy she's dating, and calls her a bitch. The re-connection leads Lee Seong-jun to messing up his life. He gets drunk and fights with his wife and moves out. He keeps playing the hideous techno version of Beethoven's 7th and breaking into tears, reminded of Haewon and how he pines for her.

Another week passes and Haewon falls asleep in the college library and dreams of a boy asking if she's dating another boy. (This is seen/shot as if it were happening.) Still later Haewon is back in Seoul and runs into Jeong-won (Kim Ui-seong), and they go to a bar and chat. He is a professor in San Diego just divorced who says he is looking for a new wife just like her. This pleases and flatters her. But does she want him, or Lee Seong-jun, or one of the boys her own age, or just flattery and success?

Hong's way of working is double-edged. On the one hand his constant reworking of themes and situations in every successive film makes for a kind of inbred pleasure, and tricky repetitions and overlappings of real and imaginary as in the recent Night and Day can be fun. On the other hand one begins to think back nostalgically to the first few Hong films one saw, when it all seemed fresh and new and original, sort of Nouvelle Vague in Korean, and they had not all begun to blur together. The question arises: is the burnout his, mine, or both? Of course Hong is far from being an auteurist Korean Woody Allen; Woody changes milieus and themes more often. But both directors make a lot of distinctively personal movies of which some work and some don't. Or all work, more or less. But afterwards some of them you don't care about.

On the other hand, with a filmmaker whose work is all so closely interrelated and flat-out repetitions as Hong Sang-soo's, the interrelations between the films are a big part of the interest and pleasure, and so it may be that in viewing his entire œuvre, or a large slice of it, in connection with Nobody's Daughter Hawwon, this latest film may come to life.

Actually more than Woody Allen Hong Sang-soo obviously resembles Eric Rohmer. He, like Rohmer, focuses on people who always want to be with the wrong person, or like Melvil Poupaud in Rohmer's 1996 Tale of Summer, just can't decide among several. Haewon certainly has several, but she doesn't even seem to want to decide; she's just killing time, or trying to forget that she misses her mother.

Nobody's Daughter Haewon , 90 mins., the director's 14th feature, debuted at Berlin (February) and has shown at four or five other festivals, and was screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival in September 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:17 PM.

-

Roger Mitchell: LE WEEK-END (2013)

ROGER MITCHELL: LE WEEK-END (2013)

Jim Broadbent and Lindsay Duncan in Le Week-End

An aging English couple's wry anniversary in Paris

Le Week-End is a rather bitter, yet safe, little comedy about sixty-somethings that will please the mature art-house audience. Mitchell, whose Hyde Park on Hudson last year (NYFF 2012), about Roosevelt's meeting with England's king and queen, was on the crude side, delivers something this time with both more tone and more bite thanks to a Paris background, discreet chamber jazz, performances by Jim Broadbent, Lindsay Duncan and Jeff Goldblum, and above all a script by Hanif Kureishi, who has collaborated with Mitchell before (with The Mother and Venus) and likes to blend laughs and home truths. His richest triumph as a screenwriter still remains My Beautiful Laundrette, done with Stephen Frears, one of the best English movies of the Eighties. Kureishi's focus seems to have narrowed and his viewpoint soured since then; a very bitter divorce and midlife crisis or crises of his own are not impossible writing influences.

These actors are so distinguished and reliable, so able at mimicking the familiarity of a long marriage, they might put one to sleep, were it not for all the thorny issues that arise between Meg Burrows (Duncan) and fellow teacher Jack (Broadbent). The theme is late (sixty-something) midlife crisis hitting a seasoned marriage whose anniversary they are celebrating with a weekend in the Ville Lumière, where they spent their honeymoon three decades hence. They seem to delight in overspending, in ways that may strain credibility: to begin with Meg summarily rejects the modest but decent little "beige" hotel they're chosen (their original one?), and ordains a costly tour ride in an open-roofed taxi to compensate and take them to a very expensive hotel where after a wait they're given the one space available, a VIP suite whose balcony overlooks the Eiffel Tower and whose bar is well-stocked with champagne, which they drink. We also see them savor several nice restaurant meals, the second in a place so upscale they are forced to "do a runner" to avoid payment. Something like this happens at the very posh hotel, except that at that point they're really in trouble.

Meanwhile there are the demands and complaints. Jack wants to revive their sex life; Meg says his touch is like being put under arrest. He persists, but she threatens divorce, or at least going off with the first Frenchman she meets at a party given by Morgan (Goldblum), an old and admiring Cambridge classmate of Jack's they run into who's won all the success that has eluded Jack. The climax is the party's dinner celebrating Morgan's new book -- his speech manages to be modest and boastful and all his behavior is a satire on American egocentrism -- where Jack replies to a toast to himself with a speech that becomes an aria of ironic self-pity about how he's in fact been a failure at everything. This includes, as we've already learned, that rude words to a student have led to his being forced into early retirement; a failure of a grown son they're only just gotten rid of who wants to come back with them; and being flat broke (if so, why this trip?). Goldblum has several little arias of his own, delivered with the panache that shows what a terrific stage actor he also is; I still remember his wonderful performance on Broadway in Pillow Man and on screen in Igby Goes Down. In a brief turn as Morgan's visiting son from a half-forgotten earlier American marriage Olly Alexander is excellent, and unique. He was quite unforgettable when I first encountered him, romantically involved with Greta Gerwig in a little 2011 movie by Alison Bagnall, The Dish & the Spoon (SFIFF 2011)

In his review of Le Week-End Dennis Harvey of Variety nicely pinpoints some of its contradictions. Morgan's quality is a "generous yet completely self-absorbed joie de vivre"; and Meg and Jack are characters who are "as familiar as they are complicated." I would add that the bickering in the first half is annoying and vaguely uninteresting despite being subtle and specific. Things pick up when Jeff Goldblum, his character too both complex and a cliché, enters the scene providing a venue for the film's climax, a sort of self-abnegating encounter session so complete and brilliant (Morgan's son, come from his whiskey and marijuana in his bedroom -- briefly shared by Jack, to sit at the dinner table, calls Jack's speech "awesome") -- that it brings Meg and Jack back together again, and Morgan comes to save them from their dilemma with the posh hotel's possible legal action and the "maxing out" of Jack's one credit card. Ultimately Kureishi's "humor" has become too realistic and bitter to be very funny, and the use of Paris interiors and exteriors has been too glitzy and conventional. But this shows that Mitchell and Kureishi can still surprise us, and they know how to find impeccable actors. Olly Alexander is the icing on the cake. Some talk about love vs. sex is as profound as the dialogue gets. Ultimately this is a film with very few false steps and a number of good moments, and yet it tends to cancel itself out and end by being a fine diversion but not terribly memorable.

Le Week-End, 93 mins., debuted at Toronto Sept. 2013, and was screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center. It opens in the UK 11 Oct. and the US 1 Nov. In France it opens on Christmas Day.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:20 PM.

-

Claude Lanzmann: THE LAST OF THE UNJUST (2013)

CLAUDE LANZMANN: THE LAST OF THE UNJUST (2013)

Claude Lanzmann in The Last of the Unjust

The last Jewish elder interviewed in the Seventies, with current additions

Lanzmann provides a coda to his monumental Holocaust documentary, Shoah, with this shorter but still very long study of the Viennese rabbi and Jewish scholar Benjamin Murmelstein, the last Jewish elder of Theresienstadt, whom he interviewed in Rome in the Seventies, when he was 70, a film that he has now reedited with the punctuation of judiciously added contemporary image and narration. Murmelstein in the Seventies interview film (which does not look dated at all) is still vigorous, feisty, and possessed of a remarkable memory. Lanzmann introduces the interview by saying Murmelstein "did not lie." But one eventually may question that familiar idea Murmelstein expresses that nobody he knew at the time or at Theresienstadt knew what was going on in the death camps, despite the fact, which he acknowledges, that Jews were being executed and cremated right there at the "model ghetto" of Theresienstadt that he helped run.

The newsworthy item is that Murmelstein had direct knowledge of Adolph Eichmann, whom he had dealings with before Eichman's deep involvement in the "Final Solution." Murmelstein debunks Hannah Arendt's description of Eichman as exemplifying "the banality of evil." Nothing banal about Eichman's evil, in Murmelstein's view. He says Eichman, even in his personal encounters with Murmelstein, was a "devil"; that he was also guilty of graft and exploitation of Jewish exportation to other countries for his own personal profit. Furthermore while in the Jerusalem trial there was no proof offered that Eichman took part in Kristalnacht, Murmelstein recounts directly observing him doing so, participating in the destruction of the holy objects of the largest synagogue of Vienna.

Murmelstein was viewed as a collaborator and a criminal, though he was tried and acquitted (no detail about this), and hence his book about Eichman and other testimony submitted to Israel at the time of the Eichman trial was not taken seriously by the Israelis. Murmelstein never went to Israel. The film does not explain what happened to Murmelstein's own family. He seems to have lived his life after the war in limbo, never able to go to England or America, where he says he might have had a career as a teacher and writer.

And what are we to think of Murmelstein? First of all, Lanzmann, who addresses the camera in French but interviewed Murmelstein in German, describes in detail the twisted origins and purposes of Theresienstadt, the "model ghetto" designed to function as a showplace cover or facade for the concentration camps. It was presented as a safe haven for elderly Jews, but when they arrived there they were greeted with humiliation, as they were by the Nazis elsewhere. Murmelstein was the third Jewish elder who "ran" Theresienstadt under the Kommandant, after the first two were sent away and executed. How did Murmelstein survive? Is the fact that he survived heroic -- or despicable? It seems that in any case he survived because he was brave, forceful and tough, both to the Nazis and in administering the "ghetto."

Murmelstein says that his aim was the survival of Theresienstadt through cooperating with the authorities in its "embellishment," the beautifying and physical improving of the facilities, and insisting that the inhabitants work 70-hour weeks. He explains how he protected their health, getting rid of typhus and lice, and asserts that his cooperation in the 1944 propaganda film about the place was an essential step, because once it had been made known as a model place, the Nazis could not eradicate it. He admits that he was of course also saving his own skin and feeding his own ego in being a strong and effective leader -- under the Nazis.

Lanzmann's lengthy, solemn, ceremonial over-and-overing documentary process seems necessary as we eventually hang on Murmelstein's and his every word -- Murmelstsin himself a forceful, vociferous speaker who makes the viewer focus intensely on him and on the day-to-day matters of his administration and his earlier interactions with Eichman that he describes. Lanzmann's magisterial filmmaking technique today involves continual breaks showing landscapes and cityscapes of Theresienstadt and other places touched on by this document. In some of them Lanzmann stands and speaks, or reads from Murmelstein's book on Eichman, originally published in Italian, translated here into French. Unlike Shoah, which consists exclusively of talking heads, this time Lanzmann sometimes shows contemporary images from the Thirties and Forties, including a passage from the Theresienstadt propaganda film and a photo of Murmelstein in an office with Eichmann before he became the Elder at Theresienstadt.

But just Lanzmann standing and speaking at a now clean and beautiful outdoor space around the buildings at Theresienstadt can be impressive. Particularly memorable is Lanzmann in a space, become through his art both beautiful and horrible, where dozens of young Jewish men were hanged to frighten the others, an event Lanzmann describes in detail. In his late eighties, Lanzmann today still seems forceful and monumental himself, with a sadness and moral weight the feisty, energetic, logical Murmelstein does not quite muster.

This is the ultimate portrait of moral ambiguity. Note, however, that Murmelstein had the chance earlier of emigrating to England or America, and instead chose to remain in Austria and help other Jews to emigrate, before his final wartime job at Theresienstadt. This does not keep Murmelstein from having entered into very dubious situations, to put it mildly, in becoming the last Jewish elder of Theresienstadt. This is a role in which a man will be either compromised or dead.

The Last of the Unjust/Le dernier des injustes, 218 mins., debuted at Cannes May 2013, and was screened for this review as part of the New York Film Festival at Lincoln Center, September 2013.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2015 at 05:22 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks