-

DEMON (Marcin Wrona 2015)

MARCIN WRONA: DEMON (2015)

ITAY TIRAN (ABOVE) IN DEMON

A nightmare wedding

Demon cooks up an ambitious mess of a nightmare wedding gone wrong with spectacular crowd sequences of increasing madness and a raging rainstorm outside. Marcin Wrona, tragically dead now, a suicide at 42, has created a complex film, with an uneasy groom from abroad -- playing with a fork lift, Peter (Israeli actor Itay Tiran), or Piotr or Pyton (his identity already seeming frangible), of Polish extraction but arrived from England, unearths human remains, and may be uneasy also about the rambling disheveled house his bride has inherited, where the wedding is held. During the course of the elaborately scheduled wedding party, which must go on no matter how things fall apart and how bad the weather is outside, he becomes first disturbed, then has an epileptic fit, and finally, taken into the basement, is fully possessed by a dybbuk, the uneasy spirit of a young Jewish women, from a lost population of the region, and explaining herself in Yiddish. (Without ever overdoing it, Itay Tira gives his all in this commendable performance.) And yet the party goes on, becoming wilder and more debauched as the bride's father, Zgmunt (Andrzej Grabowski), gets everyone as drunk as possible so they won't see how things have gone wrong. A doctor, a professor, and Zgmunt cannot agree on what to do. Out into the damp dawn the revelers eventually all go, scattering away.

I was reminded of two excellent recent Russian films, Zvyagintsev's Leviaton, because here as there a building featured earlier in the film is destroyed at the end; and Yury Bykov's The Fool (ND/NF 2015), because in it there is a party at which people are called upon to remedy a disaster and they delay. The difference is that these two Russian films are harsh, vivid depictions of contemporary social, political, and moral corruption, whereas in Wrona's Polish film that is only vaguely alluded to, with more reference to the past. And Demon has been identified simply as a "horror" film, though that seems reductive and inappropriate. It's about possession, corruption, and madness and it depicts a kind of mass hysteria. But its aims and focus seem a bit hard to pin down. There seems an uncertainty of tone from scene to scene, but the blending of the comical with the horrible is not unwelcome and seems worthy of Poe, as in his remarkable short story, "The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether."

Things don't go quite right at the outset of Demon. Neither Itay Tiran, as the groom, nor Agnieszka Zulewska as Zaneta, the bride, is as appealing as one would like, and they're not as strongly established as characters as they should be. It's much more an ensemble piece from the start. A friend said this reminded him of a Chekhov play, and it does seem Chekhov gone mad, with a crowd massing behind the few isolated, ineffectual central characters. This is adapted, freely with an elaborate mise-en-scŤne whose richness makes one sad that we'll see no more from Wrone, by him with Pawel Maslona from the 2008 play Adherence by Piotr Rowicki.

Demon, 94 mins., in Polish, English, and Yiddish, debuted at Gdynia Sept. 2015 and shortly thereafter at Toronto (where it was reviewed for Variety by Joe Leyden); other festivals. Winner of Best Horror Feature at Fantastic Fest. An Orchard release. Screened for this review as part of New Directors/New Films, where it shows 26 Mar. 2016.

US theatrical release began Fri., 9 September 2016.

AGNIESZKA ZULEWSKA IN DEMON

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-08-2016 at 08:59 PM.

-

HAPPPY HOUR (Ryusuke Hamaguchi 2015)

RYUSUKE HAMAGUCHI: HAPPY HOUR (2015)

Four women in Kobe in family and marriage crises

The title of Ryusuke Hamaguchi's long film, Happy Hour, is ironic. His four female protagonists, Jun (Rira Kawamura), Akari (Sachie Tanaka), Sakurako (Hazuki Kikuchi) and Fumi (Maiko Mihara), all 37, friends since they were in junior high, move much closer to quiet desperation than happiness in their lives and marriages during the course of the action. What may seem at first glance little more than a classy Japanese soap, has a delightfully soothing epic quietude that links it back to Ozu. For the first three and a half hours, its restrained, very Japanese scenes of concealment and revelation, apology and withholding of forgiveness, are quite wonderful. At that point the unconscionably long public reading of a novel manuscript by a young woman writer, Yuzuki Nose (Ayaka Shibutani), occurs, some of the characters become wild and distraught, and the last hour seems longer than the first three. Perhaps it had to be that way: if Hamaguchi knew how to tie things off neatly, he'd have made a film of normal length. (Happy Hour was shown and got an acting prize at Locarno, a festival that seems to favor long-running movies.)

The marathon run-time allows for the novelistic (or mini-series) pleasure of not only playing out individual scenes in something more like real time, but also taking close looks at multiple relationships -- Scenes from Several Marriages, as it were. For a non-Japanese the four award-winning actresses, relative novices whose roles were developed in workshops, may be a little hard to tell apart; but if they seem similarly ordinary, it's precisely Hamaguchi's intention to avoid the flashy. The first scene makes them seem rather plain as they sit at a picnic on a mountain on a day trip, looking over the Kobe skyline shrouded in a fog that one says is like their future, and planning a get-together. It's the next, much longer sequence, a little workshop with a sort of guru called Ukai (Shuhei Shibata), about "communication" (using the English word, which will crop up frequently later too) and "finding your center" -- an understated Seventies-style touchy-feely process illustrating both the uptightness of Japanese culture and its built-in gift for cooperation and reading each other's minds. But it's at the third big sequence, a dinner following the workshop where the four friends join Ukai and some others, that secrets start to come out. The workshop is fascinating, a study in shyness and openness. The dinner is revelatory, the film's ensemble work at its peak. In these first big sequences Hamaguchi and his ensemble are on a roll.

Around the table, Akari, a nurse and a divorcee, emerges as the strongest of the women (her acting seems a bit strident at first). In an impassioned speech, she declares that she has to play hard and indulge in sexual adventures to escape the grim realities of dealing daily in her job with an aging population with an overburdened medical system. But a greater revelation comes from the more complicated, seemingly withdrawn Jun: she shocks her friends by blurting out that she's seeking to divorce her scientist husband Kohei (Zahana Yoshitaka), having had an affair, and she hasn't told the other three, or told about the court case, which is horrible. This revelation disturbs the bond among the women, because they feel lied to, or deceived. They attend a divorce court session, and we hear how adamant Jun's husband is. In an attempt at reconciliation among themselves, the women go to the thermal baths of Arima -- where Jun disappears. It later emerges that she's pregnant, and that she's taken refuge at a chain of centers for women who've been denied the right to divorce their husbands. By the end both gallery manager Fumi and housewife Sakurako have followed Jun's lead and told their husbands, Takuya (Hiroyuki Miura) and Yoshihiko (Tsugumi Kugai), respectively, that they went divorces.

Men don't come off well here. Beside Jun's husband who wants to keep her in the prison of marriage even if it becomes a "hell," Fumi's long-haired editor mate Takuya, who stages the reading in her gallery and brings in Ukai to conduct the Q&A, emerges as a cold bastard; and Sakurako's Yoshi, who must contend with a young son Daiki, who gets his girlfriend pregnant, is stolid and conventionally macho, while the seemingly gracious and beautiful Ukai, when he reappears, turns out to be a soulless sexual exploiter. With the reading, which arouses memories of Hong Sang-soo, Hamaguchi starts inter-cutting it with other scenes, doubtless aware of the need to jazz it up.

The manuscript-reading sequence may be serious, or deadpan satire. Either way playing it out in real time was a mistake. And at this point the seat-weary viewer may just be exhausted. The choppier later sequences are less satisfying than the earlier long ones, as well as more melodramatic; and people start falling down too often, the writers seeming eager to start killing off the cast but ambivalent about whether or not to actually do so. Nonetheless, Happy Hour, however flawed, is a tour de force made on a shoestring (apparently the budget was $50,000) showing Hamaguchi, who has a background in documentary, to be a director worth watching. The appreciative essay/review by Nicolas Bardot for the Rrench onoine publicaiton Film de Culte makes convincing comparisons with Jacques Rivett5e and the aforementioned Hong Sang-soo, also with a new generation of Japanese directors I haven't even heard of - Katsumi Tomita, Ayumi Sakamoto producing minimalist epics; and pointing to the visual beauties, he cites Kiyoshi Kurosawa. I'm also indebted to a website called Genkinhito, which has a detailed summary of the film, plus some reader comments showing I'm not alone in my dissatisfaction with the manuscript reading and my feeling that things go south from then on.

Happy Hour/ ハッピーアワー (HappÓ aw‚), 317 mins., debuted at Locarno (sixth ND/NF 2016 originating there); the four actresses in the principal roles received a collective best actress award there; at Singapore Hamaguchi got the best director prize. Also shown in the LFF. Reviewed by Mark Shilling in Japan Times. Also in 8 other international festivals, including New Directors/New Films (FSLC-MoMA), where it was screened for this review, showing 26 Mar. at 1 P.m. at MoMA, 27 Mar. at the same time at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center.

Fumi (Maiko Mihara), Sakurako (Hazuki Kikuchi) , Jun (Rira Kawamura), Akari (Sachie Tanaka)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-21-2016 at 07:49 PM.

-

IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY/AKHAR AYAM EL MADINA (Tamer El Said 2016)

TAMER EL SAID: IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY/AKHAR AYAM EL MADINA (2016)

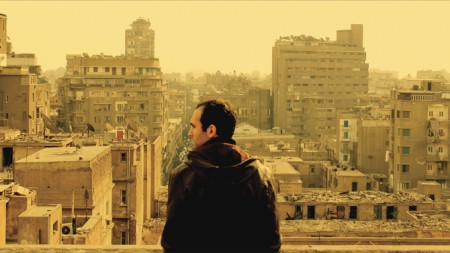

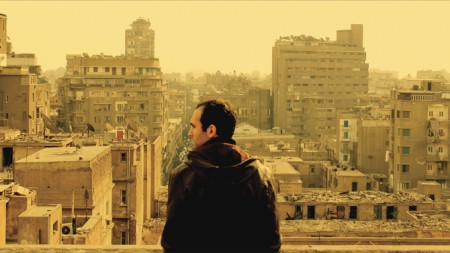

KHALID ABDALLAH IN IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY

Song of frustration and stasis

Tamer El Said's beautiful, skillfully wrought, but frustratingly stagnant feature film debut, In the Last Days of the City, is meant as a requiem and an elegy for a Cairo that's gone or perpetually crumbling. Hasn't it always been so? Perhaps, as Jay Weissberg wrote in a detailed, appreciative review in Variety after seeing its debut at Berlin, this is a work "of profound weight and intricate sadness." It's a film drenched in beauty. But it feels maddeningly futile and useless.

Last Days is unquestionably an urban visual poem about what is, however crumbling and stifled, one of the world's greatest and most vibrant cities. The images are all drenched in yellow filter, and artistic to a fault. Notice the wire cyclist on the windowsill with the cityscape beyond, and how the camera lingers on a dissolving cake of powder in a flower vase in the hospital room. Notice how the light sings at dawn behind figures along the Corniche. Having lived in Cairo for several years myself (in the Sixties) and loving urban photography, I'm entranced and made nostalgic by the constant flow of beautiful, unmistakably Cairene images in In the Last Days of the City.

But I'm also frustrated by having to watch the protagonist-filmmaker Khalid (Khalid Abdallah of The Kite Runner and The Square), who seems vaguely handsome but perpetually ineffectual, wander through nearly every frame accomplishing nothing. Yes, he has a camera in his hand. He meets with a sad-faced girlfriend (Laila Samy) who's soon going to leave the country, with a mature woman who apparently does movie voiceovers, and with a generic trio of Arab artist-filmmaker friends from Baghdad (Hayder Helo), Beirut (Bassem Fayad), and Berlin (Basim Hajar). After an enthusiastic reunion in Cairo, they exchange occasional brief conversations, and send Khalid footage -- from Beirut and Baghdad, at least. And we glimpse a very old Iraqi calligrapher, who crafts the beautifully written end credits of the film. Other characters come and go: an acting teacher who longs for a lost Alexandria (Hanan Yousef), his editor (Islam Kamal); a colleague of his late father (Fadila Tawfik) . But these vignettes don't create a sense of action.

Futilely, Khalid goes with a tall, scruffy estate agent (Mohamed Gaber) to look at apartments, because for some reason he must leave his. (These visits are glimpses of decay, shabbiness, and the oppressive encroachment of Muslim fundamentalism.) He edits his film, or looks at shots from it. And very often, he goes to the hospital where his mother (Zeinab Mostafa) lies, suffering from a generic malaise: "you've gotten old," he tells her.

The trouble is that all this, especially for a city and a population that are perhaps the most joyfully and irrepressibly in-your-face in the world, is far too detached a portrait, far too solipsistic. There's too little direct, intense interaction with what's happening in the city, or with people outside Khalid's sphere -- though, granted, we see thousands of them, in the teeming streets. The feel and look of Cairo are wonderfully captured: but at an aestheticized, somewhat humorless and self-important remove.

There is a self-reflexive concept at work in Last Days, with technique to burn. Notice how neatly the film slides back and forth from events happening on screen to their manipulation on an editing screen. And then you realize you're watching both a film about the inability to complete a film about Cairo and the filmmaker wandering around, unable to complete his film. Self-reflexive filmmaker paralysis has never been done better. Perhaps Cairo is the perfect place to stage such convolution. It is the largest city in Africa, it is or was, or still is if there still is, the cultural center of the Arab world today. And yet the crushing of the great hope of the recent "Youth Revolution of 25 January" 2011 now mires Egypt in a regime more repressive than the one they revolted against.

But is this what Khalid wants to talk about in his uncompleted film? No -- because he began making his film in 2009, and the timetable of this film is unclear. We hear some intense (and typically well filmed) anti-Mubarak chants at street demonstrations, and when Khalid meets up with his friends from Baghdad, Beirut, and Berlin, Tahrir Square is mentioned. But the 2011 revolution and the events after it, are never described.

And this vagueness is a mixed blessing. Maybe as Weissberg notes Last Days "benefits from hindsight" because it's not one of the various instant responses to the revolution that now "seem hopelessly dated" -- because the revolution has gone sour and been betrayed. However, setting the film's endless meandering flow of images and repetitious actions -- talk with the friends, meet-ups with the girlfriend, visits to the mother, trips with the estate agent -- in no particular time, it seems to lack purchase on the tumultuous events that took place since Said began his work on the film. Sadly, Said marginalizes his effort in a different way.

In the Last Days of the City/Akher Ayam El Madina/آخر أيام المدينة, 118 mins., debuted at the Berlinale 14 Feb. 2016, and is scheduled for 1 Apr. at Vilnius. Also in Buenos Aires Intl. Festival of Independent Cinema. Screened for this review as part of New Directors/New Films (NYC), showing there 26 Mar. 2016 at 1:00 p.m. at Walter Reade theater and 27 Mar. at 4 p.m. at MoMA. (Interview with the star and director at the Walter Reade Theater here.) US theatrical release of this film 27 Apr. 2018. Metacritic rating: 72%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-03-2018 at 09:29 PM.

-

CAMERAPERSON (Kirsten Johnson 2016)

KIRSTEN JOHNSON: CAMERAPERSON (2016)

A politically-conscious, left-leaning cinematographer's visual "memoir" is just a hodgepodge of clips

"How much of one’s self can be captured in the images shot of and for others?" So begins a festival blurb for this film. Well, as it turns, out, not very much, when your visual "memoir" is a tacked-together hodgepodge of one unrelated short film clip outtake after another from Darfur, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and other high-profile photojournalist venues plus scenes here at home. Such is the nature of cinematographer Kirsten Johnson's film Cameraperson. It is difficult to carry away any impression other than a shaky camera, an out-of-focus lens, and a succession of victims. These range from good-natured African ladies, who've been made homeless by marauding Arabs in Darfour (a subtitle giving the location precedes each clip), hacking off pieces of tree for firewood; to an Afghan boy with a blinded eye; to the photographer's own mother, in, a subtitle tells us, the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. In the background, Johnson can be heard pacifying, prodding, or cajoling her subjects. Her murmured words suggest a pleasant personality and the diplomatic skills to safely point a camera in many a tricky place. But not much of a personality emerges, just an awareness that this is a cinematographer with a background in hot spots.

In the scattershot series, one or two may land in the viewer's brain. I remember the smiling boy asked to say what he sees with his good, then his bad, eye; a grizzled, lean old woman in -- was it Bosnia? -- who's held up as stylish; an overwrought American woman a subtitle says has made a film about her mother's suicide, throwing a file of papers across a room in what appears to be angry frustration. What these have in common, or what they have to do with the photographer, is anybody's guess.

Kirsten Johnson indeed has a resume in which documentaries of a provocative or political nature predominate. Her work includes contributions to the "Frontline," "Wide Angle," "P.O.V." and "Independent Lens" TV documentary series. Individual films include ones about the French philosopher Derrida; the Hollywood rating system; a Teamsters strike; a departing governor pardoning death row prisoners; a banjo player touring Africa in search of his instrument's roots; New Yorker cartoons; abortion rights; women raped in the US military; hunger in America. She shot a little known documentary by Michael Moore, the 2007 Slacker Uprising. Moore is shown standing near a bunch of Marines jogging and chanting. Moore declares that it's hard to talk while running. (This would be true for him; not so much for good runners going at an easy pace.) An outtake of Derrida is equally trivial. But these are criticisms of snippets encountered in this grab bag film, not of Johnson's professional work. Her most productive and high profile partnership may be the recent one with filmmaker Laura Poitras, with whom she collaborated on the Oscar-winning Citizenfour, about NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, and the upcoming Asyum, about the ongoing problems of Wikileaks founder Julian Assange. The information in this paragraph, if linked together by a searching interview with Kirsten Johnson, might make a good documentary. But none of it is in Cameraperson: I found it on IMDb.

Cameraperson,102 mins., debuted at Sundance, where it was reviewed for Variety by Nick Schrager; also showing at the True/False and SXSW festivals, and as the closing night film of the Film Society of Lincoln Center-Museum of Modern Art's March 2016 New York New Directors/New Films series, where it was screened for this review. Public ND/NF showings 26 Mar. 6:30 p.m. at Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center, and 27 Mar. 1:30 p.m. at MoMA.

US theatrical release by Janus Films 9 Sept. 2016 (NYC). Opens 30 Sept. 2016 Opera Plaza, San Francisco and Shattuck Cinemas, Berkeley.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-24-2016 at 03:48 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks