-

TIKKUN (Avishai Siwan 2015)

AVISHAI SIWAN: TIKKUN (2015)

Another provocation for the Hasids

With Tikkun we have another movie focused on ultra-Orthodox Jews, this time a conceptual puzzler in black and white, without scored music, full of surreal elements and with shocking moments of sexuality including full frontal male nudity. What is the fascination of this community? Perhaps simply its remoteness from the lives of most people, which makes its practices seem surreal, or like an art piece. Filmmakers seem to delight in showing how its rules go wrong, as with the wife in the recent Mountain (ND/NF 2016), who is led to share cigarettes with whores in a cemetery on the Mount of Olives; or the two (male) butchers who fall in love in Eyes Wide Open, or the New York Hasidic boys who turn into drug mules in Holy Rollers.

But in Tikkun, which arouses admiration, puzzlement, and annoyance in viewers, means to present a dilemma -- though what the dilemma is, is left intentionally open-ended. A young man, Haim-Aaron (Aharon Traitel, an attractive non-professional who has a warm, appealing face), the eldest child of a kosher butcher (tall, long-bearded Khalifa Natour) and his wife (short, slight Riki Blich), seems confused and uneasy before his accident; he will seem more so thereafter. While fiddling with the shower, getting an erection, he slips and falls, knocking himself unconscious. Emergency medics give up on reviving him and decide to pronounce him dead, but Khalifa can't accept that, and, struggling to pump air back into Haim-Aaron's lungs, brings him back to life.

This is hailed as a fortunate event. But here's the rub: has Khalifa undermined the will of God, who seemed to have wanted Haim-Aaron dead? Or is it a "tikkun," in the sense of a fixing or rectification? A chance for Haim-Aaron to become a saintly, enlightened man, deeply appreciative of the gift of life? Perhaps it's an opportunity for Haim-Aaron to do good in the world.

Sometimes Tikkun, which is almost as sparing with dialogue as it is with music (of which there is none except for a celebratory Hasidic dance) makes use of mime and tableau, in a way that brings out the absurdity and oddity of the ultra-Orthodox lifestyle. Never more so than when ten men, all identical, with their dark long suits and beards and broad-brimmed hats, come to visit Haim-Aaron, standing over him and making him look tiny in his hospital bed, all exuding wordless identical goofy-chic.

In the event, Haim-Aaron seems far from "tikkun." He goes more haywire than before. He announces -- in the family of a successful butcher -- that because one must respect death (hasn't he returned from death, and in so doing, disrespected it?) he will no longer eat meat. He begins falling asleep at Yeshiva till he gets kicked out, unsleeping at home, hitchhiking and doing increasingly inappropriate things. It seems obvious that this twenty-something virgin is in search of sex, and a run-in with prostitutes, one of them grotesquely fat, follows.

Avishai Siwan, for whom this is the sophomore effort, and his cinematographer, Shai Goldman, and editors, Nili Feller and Sivan, continually roll out events in a mix of shots that is surprising, coy, and sly, as well as surreal and comic (while Khalifa's oddball dreams of lizards and toilets seem just a little vulgar). Unfortunately, Haim Aaron's adventures fall rather flat. Surreal mime is a storytelling method that's hard to sustain interestingly, or hard for them, anyway. The climax, which occurs in a fog surrounding a fatal car accident, and a bloody bed, somewhat counteracts this flatness. But Siwan's film seemed disappointing to me. Its puzzlements never come together. It's promise is not lived up to. Nonetheless, it has enough originality to attract the cinephile class. And there are small moments between Haim-Aaron and his little brother Yanke (Gur Sheinberg) that add a touch of sweetness. Shots of the narrow streets of the ultra-religious Mea Shearim district of Old Jerusalem have an appealing claustrophobic oddity. We have seen such streets before -- in our dreams.

I can add little to the review of Tikkun by Dennis Harvey written at Mill Valley for Variety Oct. 2015 in which he describes the thought-provoking aspects of this film, which he not inaptly calls "willfully enigmatic."

Tikkun, 120 mins. debuted at Jerusalem 10 July 2015, followed by Locarno, awards at both venues, and showing at about a dozen other international festivals including Telluride, Vancouver, the Hamptons, Chicago, and Stockholm. Latterly included in New York's FSLC/MoMA-sponsored New Directors/New Films, where it was screened for this review. Limited release in Israel 3 Dec. 2015. Slated for US theatrical release 10 June 2016 (NYC) by Kino Lorber.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-23-2016 at 05:23 PM.

-

PETER AND THE FARM (Tony Stone 2015)

TONY STONE: PETER AND THE FARM (2015)

PETER DUNNING IN PETER AND THE FARM

Touchingly real documentary portrait of a lone organic farmer in Vermont

The articulate, instantly engaging narrator of this docu-portrait is Peter Dunning, a former artist with Sixties hippie sympathies for whom since he was 35, 35 years ago, his 187-acre Mile Hill Farm in rural Vermont has been more important than anything else. "I am the farm and the farm is me," he says, in part of an articulate running commentary that bursts from every vivid frame. Tony Stone's intimate camera follows even the dirty, brutal side of the work, like Peter butchering, skinning, and gutting a sheep and a vet reaching inside a cow to see if she's pregnant and wrestling with an aging John Deere hay bailing machine, with the eagerness of a young man eager to learn from someone with deep experience.

Peter Dunning is a flawed individual and partly an unlucky one. His switch to farming away from a possible career as a painter and sculptor, which he studied to be when young, may be connected to a hand mangled working at a saw mill in his late twenties. What emerges is a life of endurance and dedication that has rather soured over the years as livestock have died out (coyotes have done serious harm in the past year), the buildings have sagged, the weeds have grown, and the man who has done all the work alone has aged and grown into deeper and more dangerous alcoholism. This idyllic place has become a prison in the years -- he says the farm was at its peak of production, when friends and family were all working happily together, in 1999 -- since his wife has run out on him (he's lost two marriages) and his grown children now won't even talk to him on the phone any more. And, worst of all, he knows the drinking is eating away at his soul. Thoughts of suicide seem a daily thing. The F-word flies in every sentence. The tough work of the farm that looked like fun 35 years ago now doesn't.

This is, of course, not an "objective" film. Would cool detachment while filming a man living and describing his life on the land even make sense? Not when Dunning says he feels closer to the filmmaker and his cameraman, than he ever has to any men. They stay out of Dunning's way, but the grown-closeness shows when Stone (sometimes glimpsed) worries or seems to criticize and Dunning seems wounded or angry. But mostly the sense of a seasoned relationship works well, shows in the film's way of making you feel you're there, watching, listening, smelling the barn smells while Dunning tells his stories and explains his processes. And he tells all and explains all clearly and vividly from first to last, the reason why this is a watchable and worthwhile film.

Peter and the Farm, 92 mins., shows in the True/False documentary festival 6 March 2016 and New Directors/New Films, 24 March 9:00 p.m. at MoMA and Friday, March 25, 6:30 p.m. at Lincoln Center. Screened as part of ND/NF for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-08-2016 at 07:39 PM.

-

NEON BULL/BOI NEON (Gabriel Mascaro 2015)

GABRIEL MASCARO: NEON BULL/BOI NEON (2015)

JULIANO CAZARRÉ IN NEON BULL

Tale of rodeo roustabouts breaks the barriers between documentary and fiction

Gabriel Mascaro is a Brazilian documentary filmmaker who has turned to fiction films -- but not entirely: his two features are drenched in exotic real life atmosphere. Both his 2014 debut feature August Winds and his follow-up Neon Rodeo are so steeped in realism they feel like documentaries, but with a visual beauty and sensuality and vague plot line that only conscious manipulation could make happen. Yet it's troubling to see things happen that are "real." Neon Bull takes some thinking about, and the experience it offers is a confusing one. It left me puzzled and not wholly satisfied. But Mascaro is a heck of an interesting director.

We're following a little vaquejada rodeo troupe in Northeastern Brazil that moves a bunch (I didn't count) of silver bulls pairs of cowboys bring down in shows by trapping them with horses on both sides and one grabbing their long tails and pulling them to ground. That's the show. But it's not what this film is really about. It's about people on the fringes of that action. The macho, model-handsome Iremar (Juliano Cazarré), who's a wizard with animals, and also sews sexy costumes; the tubby, gross Zé (Carlos Pessoa), skillful with a tricky prize mare; their lady truck driver, blonde Gaega (Maeve Jinkings), who is also a sexy nightclub dancer wearing a horse-head mask and elaborate G-strings costumes crafted by Iremar; and Gaega's feisty young daughter Cacá, who often gets in trouble but holds her own in the work -- plus Junior (Vinícius de Oliveira, an actor since as a child he played a key role in the classic Central Station), who's brought in later, to replace Zé -- none of them perform in the rodeos. They're just roustabouts, traveling with the bulls, preparing the carefully powdered ends of their long tails, sleeping in hammocks, living by their wits, living their dreams. Those are their roles in the film. They're all actors.

But they're also doing these things -- cleaning up the bullshit, taming horses and such. Zé and Iremar sneak into a fancy horse fair and try to steal a prize stallion's semen -- with comically failed results. That's not the only erect penis we get to see because Iremar has sex with a pregnant woman on the big work table of clothing factory, secretly, of course, at night. These things happen. Where's the fiction? You see why I call this troubling.

The images shot by dp Diego Garcia (of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendor) are composed in wide aspect ration with a soft look where the camera is often standing a little back, to compose a landscape, most memorably a horizon with glowing crepuscular light and multiple shots of the bulls in a row framed by wooden fences. What could have been ugly and crude is unified and often handsome-looking; the color quietly glows. Handsome livestock and handsome male bodies are seen equally, as in a dark panorama of almost a dozen well-built rodeo men showering in a reddish humid scene. Never has a movie contained sensuality so gritty or photographed with such casual beauty.

Mascaro creates a keen sense of this de facto "family's" day-to-day life with a few notable incidents, but the action is meandering, with no particular goal -- and the film suffers from underdevelopment of characters and their lack of backstories, despite a unifying feel of sensuality and ignoring of gender barriers. To some viewers this may feel pointless, and the physicality disgusting at times. What holds it together is a sensuality, a wallowing in muck that seems somehow relaxed and pleasant, perhaps in a spirit that's particularly Brazilian. Iremar, Gaega, and Junior with his long hair wear thrown-together outfits, but they look stylish, despite the heat and mire and muck and shit one can almost smell. Will their marginality eventually catch up with them? Or in Brazil is dolce far almost niente a spirit that can sustain a happy life?

Peter Debruge in Variety says of Diego Garcia's images that "Selected at random, any given frame of the film might stand alone as powerfully as a Dutch genre painting (think Brueghel or Vermeer)." Boyd van Hoeij pretty well sums up the film's feel and themes in his Hollywood Reporter review when he writes of its "indirect meditation on bodies and the way they are used, both in the animal world and in the human one," with an emergent "portrait of a society in which gender and body norms are much less rigid than one would expect."

Neon Bull/Moi Neon, 100 mins., debuted in the Orizzonti section at Venice where it won the prize. The Brazilian rodeo drama also screened at the Toronto Film Festival in the inaugural Platform section (honorable mention), with a number of other nominations and awards. Screened for this review as part of the March 2016 FSLC-MoMA New Directors/New Films series. To be released in US theaters by Kino Lorber. Opens Fri. 8 Apr. 2016 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-22-2016 at 02:43 PM.

-

WEINER (Josh Krieman, Elyse Steinberg 2016)

JOSH KRIEGMAN, ELYSE STEINBERG: WEINER (2016)

ANTHONY WEINER IN WEINER

Basic documentary of Weiner's disastrous campaign for mayor of New York

Anthony Weiner, disgraced Congressman from New York, then disgraced candidate for the city's mayor, is a politician brought down by sex scandal for the digital age. His special humiliation is that his improprieties never even involved physical sex. They were all only virtual, online, social media, "sexting" (exchanges of lewd text messages), faux pas on social media, and phone sex. This film is mainly a blow-by-blow account of Weiner's mayoral campaign. He already had to contend with the almost insurmountable obstacle to election of the public's widespread disapproval of his past. But it got worse. As the campaign progressed it emerged that after his resignation from Congress he had continued to engage in multiple phone sex relationships.

It becomes clear than Weiner, whatever his liberal bone fides, his declared aim of protecting the middle class in New York City, is a seriously flawed individual. Apart from his weakness for sex-at-a-distance on multiple platforms with multiple (virtual) partners, he also has generally poor impulse control. He is seen behaving extremely as a speaker in the House while a Congressman, though his anger in defending Obama's health care plan against the Republicans is admirable, and may have been effective. Later, he is filmed by the directors frequently flying off the handle with adversaries, whether interviewers in the media or hecklers encountered in the campaign. He also seems compulsive in his persistence in campaigning against all odds. His belief that running for mayor was the best way of wiping his record clean of the 2011 scandal seems misguided. He appears perpetually in denial first of his acts and then of their seriousness. In short, he is a man in need of help. "What's wrong with you?" a prominent TV interviewer asks him. And he has no answer. In 2013 he received only 4% of the vote when Bill de Blasio was elected mayor of New York.

There is nothing special to set apart the TV-ready film by Josh Krieman and Elyse Steinberg from any other rudimentary documentary about a political campaign, with its jiggly digital images and jumpy editing. The only reason for watching it, as with many documentaries, is an interest in the subject matter. The filmmakers had exceptionally good access to Weiner and his wife. This film, like the media, focuses on scandal, presenting virtually nothing about the political issues figuring in the New york mayoral campaigns.

The special focus here is on Weiner's relation with the leading figures in his mayoral campaign, and with his wife since 2010, Huma Abedin, a leading aide to Hillary Clinton. The scandal that drove Weiner from Congress was in 2011. Well, Hillary is no stranger to politician husbands' sex scandals. But will Huda, a Muslim American with Indian and Pakistani parents who speaks fluent Arabic, be an asset to Hillary's presidential campaign? And if she will continue to be too essential to lose, will she be able to stay with the disgraced and failed politician, Anthony Weiner?

Weiner, 96 mins., debuted at Sundance 24 Jan. 2016 (where it was reviewed for Variety by Geoff Berkshire), and also showed at True/False festival 3 Mar. It will show in the New Directors/New Films FSLC-MoMA series, where it was screened for this review, 25 Mar., and it is scheduled for US theatrical release 20 May 2016. It will premiere on Showtime in Oct. 2016.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-21-2016 at 07:56 PM.

-

DEMON (Marcin Wrona 2015)

MARCIN WRONA: DEMON (2015)

ITAY TIRAN (ABOVE) IN DEMON

A nightmare wedding

Demon cooks up an ambitious mess of a nightmare wedding gone wrong with spectacular crowd sequences of increasing madness and a raging rainstorm outside. Marcin Wrona, tragically dead now, a suicide at 42, has created a complex film, with an uneasy groom from abroad -- playing with a fork lift, Peter (Israeli actor Itay Tiran), or Piotr or Pyton (his identity already seeming frangible), of Polish extraction but arrived from England, unearths human remains, and may be uneasy also about the rambling disheveled house his bride has inherited, where the wedding is held. During the course of the elaborately scheduled wedding party, which must go on no matter how things fall apart and how bad the weather is outside, he becomes first disturbed, then has an epileptic fit, and finally, taken into the basement, is fully possessed by a dybbuk, the uneasy spirit of a young Jewish women, from a lost population of the region, and explaining herself in Yiddish. (Without ever overdoing it, Itay Tira gives his all in this commendable performance.) And yet the party goes on, becoming wilder and more debauched as the bride's father, Zgmunt (Andrzej Grabowski), gets everyone as drunk as possible so they won't see how things have gone wrong. A doctor, a professor, and Zgmunt cannot agree on what to do. Out into the damp dawn the revelers eventually all go, scattering away.

I was reminded of two excellent recent Russian films, Zvyagintsev's Leviaton, because here as there a building featured earlier in the film is destroyed at the end; and Yury Bykov's The Fool (ND/NF 2015), because in it there is a party at which people are called upon to remedy a disaster and they delay. The difference is that these two Russian films are harsh, vivid depictions of contemporary social, political, and moral corruption, whereas in Wrona's Polish film that is only vaguely alluded to, with more reference to the past. And Demon has been identified simply as a "horror" film, though that seems reductive and inappropriate. It's about possession, corruption, and madness and it depicts a kind of mass hysteria. But its aims and focus seem a bit hard to pin down. There seems an uncertainty of tone from scene to scene, but the blending of the comical with the horrible is not unwelcome and seems worthy of Poe, as in his remarkable short story, "The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether."

Things don't go quite right at the outset of Demon. Neither Itay Tiran, as the groom, nor Agnieszka Zulewska as Zaneta, the bride, is as appealing as one would like, and they're not as strongly established as characters as they should be. It's much more an ensemble piece from the start. A friend said this reminded him of a Chekhov play, and it does seem Chekhov gone mad, with a crowd massing behind the few isolated, ineffectual central characters. This is adapted, freely with an elaborate mise-en-scène whose richness makes one sad that we'll see no more from Wrone, by him with Pawel Maslona from the 2008 play Adherence by Piotr Rowicki.

Demon, 94 mins., in Polish, English, and Yiddish, debuted at Gdynia Sept. 2015 and shortly thereafter at Toronto (where it was reviewed for Variety by Joe Leyden); other festivals. Winner of Best Horror Feature at Fantastic Fest. An Orchard release. Screened for this review as part of New Directors/New Films, where it shows 26 Mar. 2016.

US theatrical release began Fri., 9 September 2016.

AGNIESZKA ZULEWSKA IN DEMON

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-08-2016 at 08:59 PM.

-

HAPPPY HOUR (Ryusuke Hamaguchi 2015)

RYUSUKE HAMAGUCHI: HAPPY HOUR (2015)

Four women in Kobe in family and marriage crises

The title of Ryusuke Hamaguchi's long film, Happy Hour, is ironic. His four female protagonists, Jun (Rira Kawamura), Akari (Sachie Tanaka), Sakurako (Hazuki Kikuchi) and Fumi (Maiko Mihara), all 37, friends since they were in junior high, move much closer to quiet desperation than happiness in their lives and marriages during the course of the action. What may seem at first glance little more than a classy Japanese soap, has a delightfully soothing epic quietude that links it back to Ozu. For the first three and a half hours, its restrained, very Japanese scenes of concealment and revelation, apology and withholding of forgiveness, are quite wonderful. At that point the unconscionably long public reading of a novel manuscript by a young woman writer, Yuzuki Nose (Ayaka Shibutani), occurs, some of the characters become wild and distraught, and the last hour seems longer than the first three. Perhaps it had to be that way: if Hamaguchi knew how to tie things off neatly, he'd have made a film of normal length. (Happy Hour was shown and got an acting prize at Locarno, a festival that seems to favor long-running movies.)

The marathon run-time allows for the novelistic (or mini-series) pleasure of not only playing out individual scenes in something more like real time, but also taking close looks at multiple relationships -- Scenes from Several Marriages, as it were. For a non-Japanese the four award-winning actresses, relative novices whose roles were developed in workshops, may be a little hard to tell apart; but if they seem similarly ordinary, it's precisely Hamaguchi's intention to avoid the flashy. The first scene makes them seem rather plain as they sit at a picnic on a mountain on a day trip, looking over the Kobe skyline shrouded in a fog that one says is like their future, and planning a get-together. It's the next, much longer sequence, a little workshop with a sort of guru called Ukai (Shuhei Shibata), about "communication" (using the English word, which will crop up frequently later too) and "finding your center" -- an understated Seventies-style touchy-feely process illustrating both the uptightness of Japanese culture and its built-in gift for cooperation and reading each other's minds. But it's at the third big sequence, a dinner following the workshop where the four friends join Ukai and some others, that secrets start to come out. The workshop is fascinating, a study in shyness and openness. The dinner is revelatory, the film's ensemble work at its peak. In these first big sequences Hamaguchi and his ensemble are on a roll.

Around the table, Akari, a nurse and a divorcee, emerges as the strongest of the women (her acting seems a bit strident at first). In an impassioned speech, she declares that she has to play hard and indulge in sexual adventures to escape the grim realities of dealing daily in her job with an aging population with an overburdened medical system. But a greater revelation comes from the more complicated, seemingly withdrawn Jun: she shocks her friends by blurting out that she's seeking to divorce her scientist husband Kohei (Zahana Yoshitaka), having had an affair, and she hasn't told the other three, or told about the court case, which is horrible. This revelation disturbs the bond among the women, because they feel lied to, or deceived. They attend a divorce court session, and we hear how adamant Jun's husband is. In an attempt at reconciliation among themselves, the women go to the thermal baths of Arima -- where Jun disappears. It later emerges that she's pregnant, and that she's taken refuge at a chain of centers for women who've been denied the right to divorce their husbands. By the end both gallery manager Fumi and housewife Sakurako have followed Jun's lead and told their husbands, Takuya (Hiroyuki Miura) and Yoshihiko (Tsugumi Kugai), respectively, that they went divorces.

Men don't come off well here. Beside Jun's husband who wants to keep her in the prison of marriage even if it becomes a "hell," Fumi's long-haired editor mate Takuya, who stages the reading in her gallery and brings in Ukai to conduct the Q&A, emerges as a cold bastard; and Sakurako's Yoshi, who must contend with a young son Daiki, who gets his girlfriend pregnant, is stolid and conventionally macho, while the seemingly gracious and beautiful Ukai, when he reappears, turns out to be a soulless sexual exploiter. With the reading, which arouses memories of Hong Sang-soo, Hamaguchi starts inter-cutting it with other scenes, doubtless aware of the need to jazz it up.

The manuscript-reading sequence may be serious, or deadpan satire. Either way playing it out in real time was a mistake. And at this point the seat-weary viewer may just be exhausted. The choppier later sequences are less satisfying than the earlier long ones, as well as more melodramatic; and people start falling down too often, the writers seeming eager to start killing off the cast but ambivalent about whether or not to actually do so. Nonetheless, Happy Hour, however flawed, is a tour de force made on a shoestring (apparently the budget was $50,000) showing Hamaguchi, who has a background in documentary, to be a director worth watching. The appreciative essay/review by Nicolas Bardot for the Rrench onoine publicaiton Film de Culte makes convincing comparisons with Jacques Rivett5e and the aforementioned Hong Sang-soo, also with a new generation of Japanese directors I haven't even heard of - Katsumi Tomita, Ayumi Sakamoto producing minimalist epics; and pointing to the visual beauties, he cites Kiyoshi Kurosawa. I'm also indebted to a website called Genkinhito, which has a detailed summary of the film, plus some reader comments showing I'm not alone in my dissatisfaction with the manuscript reading and my feeling that things go south from then on.

Happy Hour/ ハッピーアワー (Happî awâ), 317 mins., debuted at Locarno (sixth ND/NF 2016 originating there); the four actresses in the principal roles received a collective best actress award there; at Singapore Hamaguchi got the best director prize. Also shown in the LFF. Reviewed by Mark Shilling in Japan Times. Also in 8 other international festivals, including New Directors/New Films (FSLC-MoMA), where it was screened for this review, showing 26 Mar. at 1 P.m. at MoMA, 27 Mar. at the same time at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center.

Fumi (Maiko Mihara), Sakurako (Hazuki Kikuchi) , Jun (Rira Kawamura), Akari (Sachie Tanaka)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-21-2016 at 07:49 PM.

-

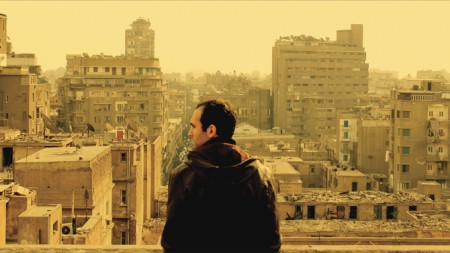

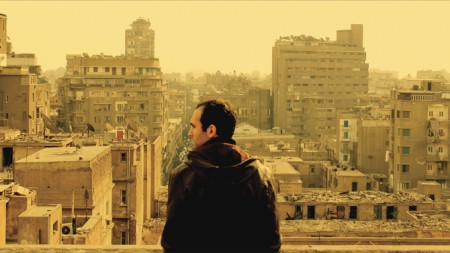

IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY/AKHAR AYAM EL MADINA (Tamer El Said 2016)

TAMER EL SAID: IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY/AKHAR AYAM EL MADINA (2016)

KHALID ABDALLAH IN IN THE LAST DAYS OF THE CITY

Song of frustration and stasis

Tamer El Said's beautiful, skillfully wrought, but frustratingly stagnant feature film debut, In the Last Days of the City, is meant as a requiem and an elegy for a Cairo that's gone or perpetually crumbling. Hasn't it always been so? Perhaps, as Jay Weissberg wrote in a detailed, appreciative review in Variety after seeing its debut at Berlin, this is a work "of profound weight and intricate sadness." It's a film drenched in beauty. But it feels maddeningly futile and useless.

Last Days is unquestionably an urban visual poem about what is, however crumbling and stifled, one of the world's greatest and most vibrant cities. The images are all drenched in yellow filter, and artistic to a fault. Notice the wire cyclist on the windowsill with the cityscape beyond, and how the camera lingers on a dissolving cake of powder in a flower vase in the hospital room. Notice how the light sings at dawn behind figures along the Corniche. Having lived in Cairo for several years myself (in the Sixties) and loving urban photography, I'm entranced and made nostalgic by the constant flow of beautiful, unmistakably Cairene images in In the Last Days of the City.

But I'm also frustrated by having to watch the protagonist-filmmaker Khalid (Khalid Abdallah of The Kite Runner and The Square), who seems vaguely handsome but perpetually ineffectual, wander through nearly every frame accomplishing nothing. Yes, he has a camera in his hand. He meets with a sad-faced girlfriend (Laila Samy) who's soon going to leave the country, with a mature woman who apparently does movie voiceovers, and with a generic trio of Arab artist-filmmaker friends from Baghdad (Hayder Helo), Beirut (Bassem Fayad), and Berlin (Basim Hajar). After an enthusiastic reunion in Cairo, they exchange occasional brief conversations, and send Khalid footage -- from Beirut and Baghdad, at least. And we glimpse a very old Iraqi calligrapher, who crafts the beautifully written end credits of the film. Other characters come and go: an acting teacher who longs for a lost Alexandria (Hanan Yousef), his editor (Islam Kamal); a colleague of his late father (Fadila Tawfik) . But these vignettes don't create a sense of action.

Futilely, Khalid goes with a tall, scruffy estate agent (Mohamed Gaber) to look at apartments, because for some reason he must leave his. (These visits are glimpses of decay, shabbiness, and the oppressive encroachment of Muslim fundamentalism.) He edits his film, or looks at shots from it. And very often, he goes to the hospital where his mother (Zeinab Mostafa) lies, suffering from a generic malaise: "you've gotten old," he tells her.

The trouble is that all this, especially for a city and a population that are perhaps the most joyfully and irrepressibly in-your-face in the world, is far too detached a portrait, far too solipsistic. There's too little direct, intense interaction with what's happening in the city, or with people outside Khalid's sphere -- though, granted, we see thousands of them, in the teeming streets. The feel and look of Cairo are wonderfully captured: but at an aestheticized, somewhat humorless and self-important remove.

There is a self-reflexive concept at work in Last Days, with technique to burn. Notice how neatly the film slides back and forth from events happening on screen to their manipulation on an editing screen. And then you realize you're watching both a film about the inability to complete a film about Cairo and the filmmaker wandering around, unable to complete his film. Self-reflexive filmmaker paralysis has never been done better. Perhaps Cairo is the perfect place to stage such convolution. It is the largest city in Africa, it is or was, or still is if there still is, the cultural center of the Arab world today. And yet the crushing of the great hope of the recent "Youth Revolution of 25 January" 2011 now mires Egypt in a regime more repressive than the one they revolted against.

But is this what Khalid wants to talk about in his uncompleted film? No -- because he began making his film in 2009, and the timetable of this film is unclear. We hear some intense (and typically well filmed) anti-Mubarak chants at street demonstrations, and when Khalid meets up with his friends from Baghdad, Beirut, and Berlin, Tahrir Square is mentioned. But the 2011 revolution and the events after it, are never described.

And this vagueness is a mixed blessing. Maybe as Weissberg notes Last Days "benefits from hindsight" because it's not one of the various instant responses to the revolution that now "seem hopelessly dated" -- because the revolution has gone sour and been betrayed. However, setting the film's endless meandering flow of images and repetitious actions -- talk with the friends, meet-ups with the girlfriend, visits to the mother, trips with the estate agent -- in no particular time, it seems to lack purchase on the tumultuous events that took place since Said began his work on the film. Sadly, Said marginalizes his effort in a different way.

In the Last Days of the City/Akher Ayam El Madina/آخر أيام المدينة, 118 mins., debuted at the Berlinale 14 Feb. 2016, and is scheduled for 1 Apr. at Vilnius. Also in Buenos Aires Intl. Festival of Independent Cinema. Screened for this review as part of New Directors/New Films (NYC), showing there 26 Mar. 2016 at 1:00 p.m. at Walter Reade theater and 27 Mar. at 4 p.m. at MoMA. (Interview with the star and director at the Walter Reade Theater here.) US theatrical release of this film 27 Apr. 2018. Metacritic rating: 72%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 05-03-2018 at 09:29 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks