-

THE BIG BAD FOX & OTHER TALES ( Patrick Imbert, Benjamin Renner 2017)

PATRICK IMBERT, BENJAMIN RENNER: THE BIG BAD FOX & OTHER TALES/LE GRAND RENARD MÉCHANT & AUTRES CONTES (2017)

[CAPSULE REVIEW]

Whoever thinks that the countryside is calm and peaceful is mistaken. In it we find especially agitated animals, a Fox that thinks it's a chicken, a Rabbit that acts like a stork, and a Duck who wants to replace Father Christmas. If you want to take a vacation, keep driving past this place. French hand-drawn animated doesn't really bring anything too negative into the picture. It's notable for its lightheartedness and intentional simplicity.

The Big Bad Fox & Other Tales/Le grand renard méchant & autres contes, 83 mins., debuted as a work-in-progress at Annecy; about a dozen other international festivals, including the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review.

SHOWTIMES SFIFF:

Sunday, April 8, 2018 at 1:00 p.m. at Castro Theatre

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-16-2018 at 05:10 PM.

-

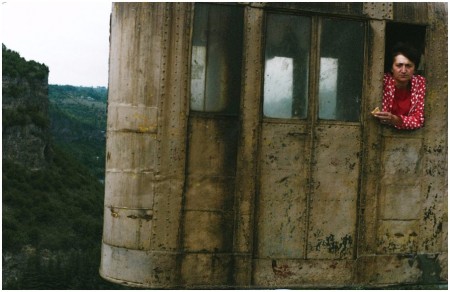

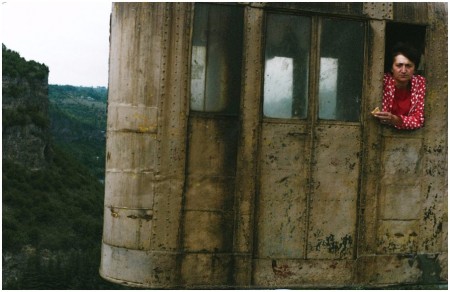

CITY OF THE SUN (Rati Oneli 2017)

RATI ONELI: CITY OF THE SUN/ბერლინი) (2017) მზის ქალაქი

A fading mining town in Georgia poetically examined

Oneli lived in New York for years, then came here to Georgia, made this cool, elegiac documentary, and has remained. The city of Chiatura once was a major supplier of the world's manganese; no more. It is a big empty shell. The film moves around with a cool eye following a few people. Much distinctive use is made by cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan of middle-distance and long-distance shots, and editing where camera position changes but continuity of sound and dialogue is never lost. This craftsmanship belies an editing style that shifts subjects with ironic randomness.

Some What do they do in the mine? How many buildings are empty, abandoned? men are still working in the mine. From a toast declared, they are still dying there. One miner performs in a local amateur theater. A music teacher, frustrated with his ten or twelve year old boys, performs songs for adults, and the rest of his time tears up a building to get the metal wiring that he sells to support himself. A phone call shows it keeps getting stolen. Two girls train as distance runners for the Olympics. They are promising athletes, but money needs to be raised to feed them: they are getting only one meal a day.

The camera observes these things, and dreary celebrations in partly abandoned buildings, with a distant, patient eye.

In one particularly fine shot the camera is twenty or thirty feet away from a large square window. Inside we see young girls at a party, dancing back and forth, perfectly framed. Sometimes the camera, still, simply observes a landscape, an overgrown mine hillside, or a crossroads in a sudden heavy rain. Or people traveling on what seems rickety public transport. It follows the music teacher to a former "Ministry of Communications" that is now just a shabby hall, where men and women, dressed up a bit, or the women anyway, joke, eat, drink and dance and get drunk, while he sings for them a song of his own composition, which they ignore. They say loud goodnights outside, and inside, the musician sits at the big table and consumes their leftovers. You can't make things like this up, and normally, you can't capture them on film.

See the discussion in Cinevue, and a live interview with Oneli (not as revealing as it might have been) in Fred. This film may feel stingy or disjointed to the casual viewer, but it contains the fruits of extraordinary patience and a distinctive vision. A dreamlike adventure in a nowhere wonderland of bygone mysteries. Stay around for the men drinking in an abandoned mine place by the golden light of an open fire toward the end clinking glasses to a "Grey world, grey century, grey town. Amen."

The title comes from an early utopian work by the Italian Dominican philosopher Tommaso Campanella, written in Italian in 1602, shortly after Campanella's imprisonment for heresy and sedition "A Poetical Dialogue between a Grandmaster of the Knights Hospitallers and a Genoese Sea-Captain, his guest." The closing end-quote it provides to the film is "They are rich because they want nothing, poor because they possess nothing, and consequently they are not slaves to circumstances, but circumstances serve them."

City of the Sun/მზის ქალაქი (Mzis kalaki), 104 mins., debuted at the Berlinale, and was shown in six other festivals, including the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened for this review. There, it received Special Jury Mention, McBaine Documentary Feature. The jury granted this mention to Oneli’s film 'for its stunning use of cinematography and sound design that immerses us in a place that is at once stark and stirring."

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-16-2018 at 04:44 PM.

-

THE NEXT GUARDIAN (Arun Bhattarai, Dorottya Zurbó 2017)

ARUN BHATTARAI, DOROTTYA ZURBÓ: THE NEXT GUARDIAN (2017)

GEMTO AND TASHI SHARE A LAUGH IN THE NEXT GUARDIAN

Family misfits at a Buddhist monastery in Bhutan

The filmmaker pair closely follow their subjects for a while, then leave them with all up in the air. We meet the goofy dad, blessing people for money with a giant phallus and dancing clumsily with a mask. He runs a family inherited Tibetan Buddhist temple-monastery in Bhutan and he and his wife have two grown kids. We see them, Gyemto, the son, and Tashi, the daughter, joyously playing and training in soccer ball-handling. They gossip together about girls, which both are interested in, and they are on Facebook.

Dad wants Gyemto to attend monk training and take over the temple with more religious education than he had time to get, but he must finish studying in English school too; his mother sagely advises that people need English now, and he would need it to take foreign visitors around. We follow Tashi, who, as dad says, has long had "the soul of a boy," to girls soccer camp where she expects to get chosen for the national team.

Tashi does not get chosen. Dad takes Gyemto to the monastery where he wants him to train. It sounds grim. At this point, Gyemto stops talking to his father. And the father rattles on in a sort of singsong voice, with many gestures. No pressure, but if you don't do this, our patrimony will be taken away from us by the Buddhists or the government. But do what you want. No wonder Gyemto doses off that evening, as the drone goes on. But while he shuts down, he does not actively rebel and has told Tashi that if told to go to the monastery, he will do so.

Gyemto and Tashi still are best mates, still look at girls together. She begs him not to go to the monastery because then she will be alone. But at film's end, it's all up in the air.

This is another example of a documentary where the filmmakers have done a skillful job, mostly, of completely concealing that they are there, or hidden from us how much they may have influenced events. Congrats to everybody for not looking into the camera. But one feels a little cheated in more ways than one, though the scenery and settings are colorful and beautiful and the siblings are cute. Often documentaries fall into more or different things happening than they bargained for. This time less seems to happen than might have been expected. In a way this is novel and it takes a certain courage for the filmmakers to sit with it. But maybe they should have sat longer.

The Next Guardian, 85 mins., debuted at IDFA, also playing at Five Flavours, Budapest International Documentary Festival, True/False and the SFIFF, as part of which it was screened for this review.

GEYEMTO AND HIS FATHER IN THE NEXT GUARDIAN

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-17-2018 at 01:24 PM.

-

THE RESCUE LIST (Alyssa Fedele, Zachary Fink 2017)

ALYSSA FEDELE, ZACHARY FINK: THE RESCUE LIST (2017)

Slavery still exists

Slavery is alive and well and practiced in various forms and venues. Studied here and vividly depicted by the recently formed San Francisco anthropologist-filmmaker team of Fedele and Fink is what happens on Lake Volta in Ghana, the largest man-made lake in the world. Boys are sold by poor families to work on fishing boats here, presumably short-term. But they often seem to disappear, and regularly remain slaves to their fisherman masters for years.

First we meet Kwame, a former slave himself, who goes around on the lake, by boat or to remote villages, demanding that boys be given up. Surprisingly, Villagers and fisherman

do listen to reason. Then Kwame takes the boy to a secret rehabilitation center called Challenging Heights were they live for a year with other boys and go to school, which whether they are 14 or 18, may be for the first time. The center searches for their families, who have to swear they will never let them go again, on pain of jail.

We meet several newly rescued boys. Edem longs for his friend Teye to be rescued too and it happens. Peter was sold at age three and not rescued till he was 18. Steven is sad and can't function. Kwame takes him to the water for a healing ritual. He seems to feel survivor guilt for another boy who died diving to untangle the fishing nets in the murky waters, a common occurrence. We can see the damage and hurt in these boys, their estrangement from normal life and from education.But we also see beautiful smiles, fresh faces, and health. The boys seem to thrive at Challenging Heights. It's like an orphanage whose members arrive with an unusually unified background experience. They eat plenty of food, play sports, watch TV, and, most of all, attend the center's school classes where they learn reading and writing and English.

After the time is up we see a boy reintegrated with his family or, in one case, taken in by the village chief, who offers him the choice of that or living with his mother. He chooses the chief over his mother.

Rarely has a film been so moving, simple, hopeful, and sad. Kwame and Challenging Heights are credited with rescuing 1,000 boys, but it's believed that 10,000 are currently slaves on the lake. It is a miserable life. They are beaten, worked and given no respite, and may drown.

The Rescue List 78 mins., debuted at the San Francisco International Film Festival, where it was screened online for this review. Also in the Full Frame, DocLands film festivals. See review by Dennis Harvey at San Francisco for Variety.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-16-2018 at 09:17 PM.

-

SULEIMAN MOUNTAIN/SULEIMAN TOO (Elizaveta Stishova 2017)

ELIZAVETA STISHOVA: SULEIMAN MOUNTAIN/SULEIMAN TOO (2017)

PERIZAT ERMANBETOVA IN SULEIMAN MOUNTAIN

About a boy - or two

A rare film made by an outsider, Russian filmmaker Elizaveta Stishova, in Kyrgyzstan, about a boy and shifty parents who reclaim him from an orphanage, then go on a road trip enacting various con games. Uluk (Daniel Daiyrbekov), who has a dour, astonished face, is more circumspect than the gypsyish "family" he gets saddled with, but he knows he's fortunate too. He gets to travel, and they buy him a toy helicopter.

Uluk's father, Karabas (Asset Imangaliev), is a charmer in his floppy-haired way, tall, with mustachios, in need of a haircut when, after an exorcism, they're flush enough to buy him a nice suit (which he doesn't seem to pay for). He frightens and then awes Uluk, then smashes his helicopter, childishly playing with it by himself.

The boy also has to contend with two wives. His mother, Zhipara, is a middle-aged woman who looks plain but does flashy exorcisms and other rituals. The pretty young wife, Turganbyubyu (Turgunai Erkinbekova), is pregnant, and emotional. Zhipara is uneasy, and has to make sure Karabas stays hooked to her in more ways than one.

One incident or village scene follows another as they travel around in an ancient East German truck, scamming money that Karabas hastens to throw away. The incidents are full of authentic local color. But they don't have quite enough dramatic meat on them. Fellini or Emir Kusturica might have done more with this potentially rich material. Here, the characters don't matter enough, particularly not enough attention is given to the little boy. And Karabas isn't ever quite awful enough so that we can enjoy forgiving him. But the road trip flavor is captured.

Much of the action is shot on location in and around the mystic World Heritage Site of the Suleiman Mountain in Osh, Kyrgyzstan.

Suleiman Mountain, 101 mins., debuted at Toronto Sept. 2017 in the Discovery section; also Palm Springs Jan. 2018; screened for this review as part of the San Francisco International Film Festival, Apr. 2018. There was a meetup watch and hike for the Sat. date.

SFIFF SHOWTIMES:

Thursday, April 12, 2018 at 6:00 p.m. at BAMPFA

Friday, April 13, 2018 at 5:30 p.m. at YBCA Screening Room

Saturday, April 14, 2018 at 2:00 p.m. at Roxie Theater

DANIEL DAIYRBEKOV IN SULEIMAN MOUNTAIN

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-17-2018 at 04:34 PM.

-

THE JUDGE (Erika Cohn 2017)

ERIKA COHN: THE JUDGE (2017)

KHOLOUD AL-FAKIH IN THE JUDGE

A female voice in female matters

This brief documentary tells the story of the first female judge of Palestine's sharia court, the first two, actually. Four have been appointed before the documentary ends in 2017, after a very different period of undermining, probably by corrupt methods, of their position. The Islamic sharia court: isn't that as conservative as you can get? Maybe not quite. At least this shows that in these times, a wedge has worked in to offset male domination. A man under this Islamic system can still have four wives. But he'll have a pretty hard time doing so if Judge Kholoud Al-Faqih is the authority consulted about it.

So what does this mean? And how did Al-Faqih and her fellow female sharia judge also appointed, Asmahan Al-Wahidi, get past conservative Islamic scholar Husam Al-Deen Afanah, who denounced the appointments, speaks disapprovingly to the camera of all this, and issued a fatwa when one woman was appointed? (A fatwa isn't normally a death threat, the Salman Rushdie case notwithstanding. It can merely just be a stern expression of disapproval by a religious authority.)

Well, we don't know all the details. We hear many on-the-street opinions, and there are a number that do favor women, perhaps more that are the reverse. (There is a dearth of sophisticated, educated opinions among those Cohn samples.) When we see and hear Kholoud, she is convincing. She is solidly authoritative, her comportment warm and pleasant, but firm and convincing. We don't hear anything from her colleague Asmahan Al-Wahidi. But we hear plenty from the Palestinian Chief Justice of the Sharia Court responsible for these first two female appointments, Sheikh Tayseer Al-Tamimi, whom Kholoud originally had petitioned to consider women sharia judges, arguing that the Hanafi school of Islam followed in Palestine does not forbid them, however revolutionary some authorities and members of the public considered it. Sheikh Al-Tamimi decided to let women compete for the post, via the necessary exams, which they passed, leading to their appointment in 2009.

We hear plenty from Kholoud, too, and see her young son and daughter when she is appointed, the son waving an iPad and declaring proudly (in Arabic: the only words in English in this film are the few spoken by Palestinian female diplomat Hanan Ashrawi), "Hey world! My mom's a judge! And my dad's a lawyer!" We also see her in action quickly deciding divorce and support and domestic violence cases - her purview - with good-natured firmness. We are surprised to learn that Chief Justice Al-Tamini has four wives and twelve children.

The trouble comes suddenly when, after several years of doing their jobs well, the two female sharia judges received a terrible blow. One year from his appointment o the two women, Chief Justice Al-Tamini was forced to resign in retaliation, and replaced by a Sheikh Yousef Al-Dais, an uninlightened figurehead of manipulators who immediately cancelled judicial qualifying exams for women, and transferred all small cases to the bigger sharia court in Rammallah, claiming that the female judges were in too much danger. The women were restricted to nothing bu administrative cases, rubber-stamping documents, not making judicial decisions. Kholoud says this was "hell."

She tried to get around the attempt to block a woman's divorce by ordering the husband to have a mental exam by public health authorities. They found him to be bipolar and dangerous. On that basis Kholoud could order him separated from his wife. Unfortuntely, this proved to be right, and when the higher Justice overruled it, and allowed the husband in a court together with his wife, he attacked and killed her - she died right in Kholoud's arms. Then in a TV court scene, Al-Tammam pledged to "punish" someone for this tragedy. Kholoud wrote to him that he was the one to blame.

It seems sharis chief justices in Palestine don't live forever like U.S. Supreme Court Justices, because in a few years Al-Youssef retired, and a new Chief Justice, Dr. Mahmoud Aa-Habbash was appointed. His first round of appointments were five men. But he allowed the smaller courts to carry out decisions again, and the two female judges were back in action. In 2015, Tahir Hammad was appointed first female In 2015 Tahir Hammad was appointed first Palestinian woman marriage officiant, a judicial rank. By 2017, the fourth Palestinian woman sharia judge was appointed, Sireen Anabousi.

So it's a slow back and forth process, but it's moving forward. And not really surprising. There have been Palestinian women judges for criminal cases since the Seventies, and Arab women lawyers. But the Islamic world is a place of machismo. And so these wedges, and the milestone represented by Kholoud Al-Fiqah as the pioneer woman sharia judge, are very important. It's a pity in Erika Cohn's effort to make Judge Al-Faqih into a kind of rock star of Islamic female authority figures, she blurs the details about the other women involved. This is a vivid film but not a subtle or thorough one.

The Judge, mins., 76 mins. (the Arabic title القاضية al-qādhiya is given), debuted Sept. 2017 at Toronto, also at DOC NYC, IDFA Amsterdam, CPX:DOX, several others, including San Francisco Apr. 2018. US theatrical release Apr. 13, 2018. Metascore 69%.

SFIFF SHOWTIMES:

Friday, April 6, 2018 at 6:00 p.m. at Roxie Theater

Saturday, April 7, 2018 a 3:30 p.m. at BAMPFA

Friday, April 13, 2018 at 12:30 p.m. at YBCA Screening Room

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-18-2018 at 03:16 PM.

-

LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE (Gustavo Salmarón 2017)

GUSTAVO SALMERÓN: LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE/MUCHOS HIJOS, UN MONO Y

UN CASTILLO (2017)

JULETA SALMERÓN IN LOTS OF KIDS, A MONKEY AND A CASTLE

She knew what would make her happy

The Spanish actor Gustavo Salmerón filmed his eccentric and buoyant mother, her husband, and her six children over 14 years on digital, super 8, and iPhone6 for this "home movie" whose extravagant eccentricity make it appealing to anyone and something essentially Spanish. The ability to survive, even enjoy, borderline crazy excess - notably an excess of possessions overflowing into a literal castle - somehow make one less afraid of ordinary problems. There is, also, plenty of action, despite the subject, Juleta Saleerón, rarely leaving the house, and sometimes holding forth from bed, a position in which she sometimes likes to give instructions as to what to do when she dies. (At the end, she is eighty.)

The title is no joke. These were the things Juleta from childhood dreamed of - and achieved. Six (living) children; for a while, a pet monkey (till it became too aggressive and had to be "given away." And, after a large inheritance fell her way, a real, huge castle, with grassy grounds, turrets, crenulated edges, and a suit of armor, along with beautiful objects, statues, paintings, and an excess of stored stuff, often in neatly labeled boxes.

This stuff, youngest son and filmmaker Gustavo and his other siblings (who all seem to be around - "that is the nice thing," Juleta says at one point. "They went away, and they came back") spend time sorting through. First just to point out the excess of it - which indeed is almost endlessly amusing, then in search of the vertebrae of her grandfather, executed by the communists in the civil war; then to move it all out, when, after the great financial crash of 2008, they are forced to give up the castle and move to their place in Madrid. Details of the rise and fall are not given, and don't matter. It is evident that Juleta's buoyancy isn't seriously dented by changes in circumstance, that her lively monogogues thrive on the prospects of adversity, that, anyway, she manages to have it pretty good much of her life.

"This is the best time of the day," she says, when she's biting into a crunchy piece of toast and sipping her milky mocha coffee. Her husband chides her for being increasingly "gorda" (fat), but she is not about to abandon any of her remaining creature comforts. And we enjoy her enjoyment.

She describes her husband, a quiet, elegant man who is deaf, and might be styled as "long-suffering," as having been a very spoiled rich boy. Bohh are conservatives. They are right wing, they are monarchists, and, in her case, they are obsessed with death. This sounds like Salvador Dalě, and it's all so Spanish it's not surprising that in the move-out from the castle, splendid pink bullfighting capes appear.

There is a literal skeleton that is rescued from the castle in the moving out. There is, by the way, her husband's (former) factory, a huge space that the family now uses as a warehouse for its endless accumulation of junk. This is where everything goes when the castle is emptied, which the family, in an economy move, seems to do most of the moving for themselves. Then later, the factory is robbed, and all the best stuff is stolen.

None of this somehow matters. Juleta remains eccentric, bubbly, glittering and glamorous. And planning her own death - but not just yet. I laughed a lot, and sat close to the screen, eager to see what would come next. The film ends with a review of early footage of the six children. They are very handsome.

Lots of Kids, a Monkey and a Castle/Muchos hijos, un mono y un castillo, 91 mins., debuted at Karlovy Vary Film documentary competition, July 2017, winning the top prize about two dozen fests including Toronto, London, DOC NYC, and (Apr. 2018) the San Francisco International Film Festival, as part of which it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-18-2018 at 11:01 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks