-

TRANSIT (CHristian Petzold 2018)

CHRISTIAN PETZOLD: TRANSIT (2018)

PAULA BEER AND FRANZ ROGOWSKI IN TRANSIT

Loneliness, fear, loss, alienation, suicide, fluid identity in a war story out of time

When a man flees France after the Nazi invasion, he assumes the identity of a dead author whose papers he possesses. Stuck in Marseilles, he meets a young woman desperate to find her missing husband - the very man he eventually turns out to be impersonating. Christian Petzold casts Franz Rogowski and Paula Beer in his adaptation of Anna Seghers' novel Transit Visa, set in the 1942 Marseilles zone libre (free zone). What he does with the source is strange and intriguing, and creates a memorably haunting mood if you give yourself to its peculiar mysteries. My faithfulness to Petzold remains, even when he's working without his muse, Nina Hoss (he finds a good equivalent in Paula Beer). This is a distinctive, difficult, but potentially very rewarding film.

"There are those who treat melodrama as a dirty word" wrote Guy Lodge in Variety, "but no working filmmaker gives it a cleaner, crisper reputation than German auteur Christian Petzold, whose extraordinary anti-historical experiment Transit nonetheless registers as his most conceptually daring film to date." "Anti-historical experiment" because Petzold tells Seghers' Forties story with a contemporary background (but without ultra-current details like smart phones).

Petzold has drained the specifics of the World War II and Holocaust-related content from the material of the source novel, which is of its period and none other. The replacement semi-contemporary recreation allows connections between refugee horrors of World War II and the new ones of today, which for the first time are just as bad, with a new global pointlessness and complexity. I refer the reader to a Wikipedia plot summary (which is rather general) for the outlines.

Georg (Rogowski), "Germany’s Joaquin Phoenix," has the remnants of a split lip, a slight lisp, a taut intensity. We don't know quite what he's fleeing, while Seghers' protagonist was a concentration camp escapee. . But the WWII fugitives in Marseille, whose time was running out, as here, he seeks permission to sail to another country that will be haven. For a while he bonds with a little boy, an aspiring soccer star whose penchant he encourages. This activity best fits with the incongruously cheery, sunny Marseille exteriors. The boy has only a mute mother with whom he communicates in sign language and wants Georg to stay around; feels betrayed when Georg says he must leave. Georg later returns to their flat and they are gone; it's packed with exotic refugees.

This is a diversion, anyway. The main storyline focuses on the American consulate and the people Georg encounters there, including a woman with a pair of fancy dogs she'll be rewarded with safe harbor for bringing to South America. (That ends badly.) And there is Georg's uneasily intimate connection with the fate of a writer he's supposed to help out, Weidel. He's shown a bloody bathroom, and learns Weidel is dead by his own hand. Papers that fall into his hands, meant to go to Weidel's wife Marie (Paula Beer), eventually enable Georg to take on Weidel's identity and permission to travel. But as he comes to be in touch with Marie, he's also enmeshed with a doctor named Richard (Godehard Giese). . .

Everyone's fate and plans are in flux, and as Georg falls in love with Marie, he becomes more eager to sacrifice his own future to satisfy her dreams, deluded though they may be. Petzold takes us into a world of extraordinary pressures and fluid identities.

The fact that the film is ahistorical will alienate viewers, but also enables Petzold to create something both hauntingly Kafkaesque ("a remake of 'Casablanca' as written by Franz Kafka" David Ehrlich of Indiewire called it) - as well as a film close to the melancholy, ruminative WWII material of French 2014 Literature Nobel Patrick Modiano. It takes a while to figure out what's going on in Transit - and one of the story's characteristics is that the people don't know what their plans are, either. This is a film some will hate, and others love. If it's the latter outcome for you, this style-drenched, plot-neutral film may reward repeated viewings.

Transit, 104 mins., debuted at Berlin Feb. 2018, showing in about a dozen other international festivals, including New York, where it was screened for this review as part of the Main Slate 14 Oct. Metascore 72.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-03-2019 at 05:27 AM.

-

THE TIMES OF BILL CUNNINGHAM (Mark Bozak 2018)

MARK BOZAK: THE TIMES OF BILL CUNNINGHAM (2018)

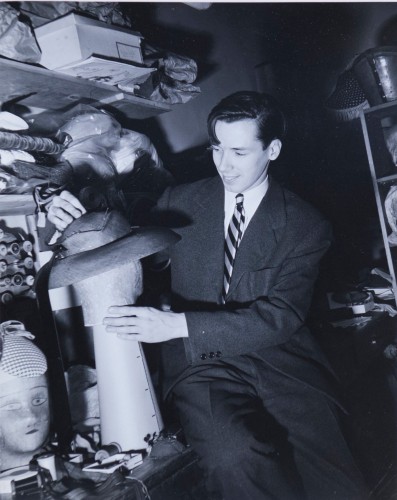

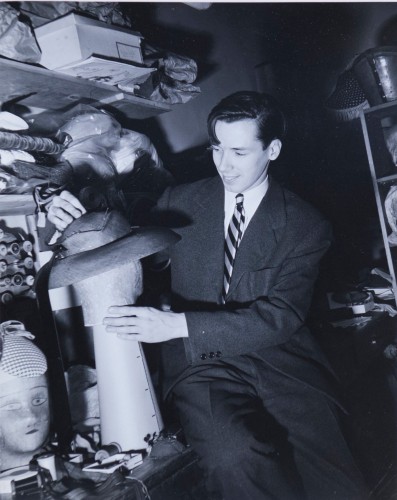

More details about the ultimate street recorder of New York fashion

This film is entirely built around an interview Mark Bozek filmed with Bill Cunningham in 1994. It ends when the film ran out. He decided to make a documentary around the interview when Cunningham died in 2016 at the age of eighty-seven. We don't know what became of this valuable film originally, but it was shot when its subject had received a Media Award from the Council of Fashion Designers of America.

This film shows a series of snappy photos purported to be of his millinery productions, and they are marvelous, and astonishingly various and numerous. Let us shed a tear for this vanished art, and wonder at the customers of "William J." (his business name, to hide it from his disapproving family), which included Marilyn Monroe. This came after a tour of duty in Europe in the Army that allowed him frequent side trips to Paris to see the fashion shows. Bozak provides glimpses of this period, too. As filmmaking, The Times of Bill Cunningham is only workmanlike, but it's still invaluable for the wealth of visual and audio information it provides.

The interview film is up close and bright. It's shows its subject's fresh innocence and energy vividly. You can see the spots on Bill's face from his days outside, hear his eager laughter. The shy, ebullient, boyish Bill is so modest he begins by dismissing the whole idea of being interviewed. He thought what he photographed was important, he himself a zero. He is by turns gushy, modest, and emotional. As the interview goes on, Bill provides an extraordinary amount of information about his life, which Bozak has illustrated and supplemented with stock footage, still and in motion, which he got access to through Bill's niece, Trish Simonson - access crucial to the film. Bill's own words are occasionally supplemented by narration by Sarah Jessica Parker. He was so distant, so odd, so focussed and intense, and though intensely friendly, socially limited. Could he have been on the spectrum? Anyway, he lived like a pauper, but he was royalty.

There are shots of his parents and his brothers and sisters. Strait-laced Boston Catholics, they didn't like his first love, designing hats, and were pleased when he discovered street fashion photography and gradually morphed into a cultural photojournalist, the most prolific and dedicated of them. "We all dress for Bill," the longtime Vogue editor famously said about him. Well, if we are interested in the immense range of stuff that happens on the street with clothes, we all care about Bill, his own designer gifts, his austere life, his free-ranging of Manhattan on multiple bikes, one of which seemed to get stolen every year. This and other facts, like the Légion d'Honneur and the Nineties adoption of the blue French workman's jacket, were already covered in Press's film.

To begin with we get another glimpse of where Bill lived on the cheap for so many years, his zen monk-ish room without bath in a since closed residential wing of Carnegie Hall. Richard Press's 2010 Bill Cunningham New York (ND/NF) brought us up to date on this situation, where, on the closing of the residential wing, an apartment was found for Bill overlooking Central Park. Here, we learn some more about that residence, and who lived there. We didn't know Marlon Brando dossed with Bill for a while when escaping from women fans.

The interview goes particularly into Bill's close friendships with Nona Park and Sophie Shonnard of Chez Ninon and how important they were for fashion at the time.

Bozak doesn't pry into the shy Bill's private feelings. In Press's film he enigmatically nods to being gay, but one might wonder if he went through life a virgin. What is clear is that in 1994 he collapses into tears instantly when asked about sad things in his life and he comes to AIDS and talks about the immense loss of creativity that scourge meant particularly in the fashion world, including so many, like Willi Smith, Perry Ellis, Halston, Patrick Kelly, Antonio Lopez, that Bill would have known. As a 2013 NYTimes piece noted, AIDS deaths, especially in the mid-seventies and early nineties, in certain gay-dominated "fields of enormous creativity and change — from art to fashion to literature — were devastated, never to recover completely." Bill Cunningham knew this. He was in the midst of it. To see this happy man suddenly so moved to tears he cannot speak is the most stirring moment of Bozak's film. We learn that Bill photographed many things (and kept the shots in his voluminous files) without publishing them, including images of the Gay Pride parade from its inception, and many years after.

But the message Bill gets to reiterate so often if finally rings out is this: he did not claim to be a photographer, like Cartier Bresson was one, but a recorder of street fashion, and that fashion was to him the true fashion, not what the designers produced but how real people wore the clothes. His life was austere and restrictive, and his shyness, he admits, sometimes made it hard to go out to the streets he seemed to dominate. But he clearly never lost his passion for the new and his gift for finding it. The austerity provided him the freedom, and he emphasizes that he could, and did, go anywhere he wanted to shoot his pictures. Cartier Bresson would not have disapproved.

The Times of Bill Cunningham, 74 mins., had its world premiere at the New York Film Festival 11 and 14 Oct. 2018. It was screened for this review.

US theatrical release finally coming 14 Feb. 2020 (New York) and 21 Feb. (Los Angeles), wider release to follow.

See: "Bill Cunningham Left Behind a Secret Memoir,"

NYTimes 21 Mar. 2018.

NYTimes 21 Mar. 2018.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-30-2020 at 09:15 AM.

-

MONROVIA, INDIANA (Frederick Wiseman 2018)

FREDEICK WISEMAN: MONROVIA, INDIANA (2018)

What is happening here?

The 88-year-old master of meticulous observation turns his attention to a farming town of under 1,500 - and planning meetings show, they don't want it to grow much. There is an undercurrent of deep irony that for all Wiseman's traditional, sometimes thrilling dedication to the quotidian, let's you see this as, well, dullsville. But this may be over-reading. Mostly Wiseman simply shows life in this red state place to be low-keyed.

If there is anything exciting going on here, it takes a while for it to appear. (That is always part of Wiseman's art, of course.) The film begins with a sequence of quick near-silent shots of houses, church, road, grass, field. All seems placid, which apparently is the dominant impression the filmmaker wants us to take away. It is almost dormant.There is o conflict. Thus begins one of the filmmaker's less interesting and less penetrating portraits of a place or an institution, a long way from his recent Ex Libris or At Berkeley, where the Boston native gradually built up a portrait of humanism and cutting edge thought. A thought that comes early here, from a local minister speaking to a group of weary middle-aged faces, is that God gives men a hard time, but makes things right in the end.

Wiseman does not focus on what may be for some of us Monrovia's telling political characteristic - this area voted 76% for Trump. Trump's name never comes up. Instead we get discussions of whether houses or businesses ought to be favored, and where to place a new bench in front of the library. Things get more exciting when a board meeting discusses the lack of a water system that provides fire protection - a bar to development (which many don't want anyway).

We see an eighty-year-old man honored in a long and tedious ceremony, in an unimpressive room and dressed in ordinary clothes, for serving as a Mason for half a century. An overweight man lectures a high school class on how outstanding Monrovia has been in basketball. The pizza place is called Dawg House. An Italian might not be best pleased by what is being turned out here.

It doesn't require selectiveness to reveal that there are vey few people here who are anything but native white Americans (there are a couple of African Americans at a high school band concert, and that's about it). Nor is unfair but only factual to point out that many people here are overweight, at all age levels.

Where things look more energetic is in agriculture. There are repeated glimpses of a hog farm that appears large scale. How large, we don't see, but the truck they are herded into at one point is ver long indeed. At an auction of used or nearly new agricultural equipment, a combine is sold for $110,000 - a bargain if you see what these things normally cost (up to $50,000).

More dispiriting is a supermarket where the camera ruthlessly surveys the goods on display and shows it to be monotonous and unhealthy. Not that people don't enjoy eating here, or that there is no good food. But there is a woman customer, bulging and shapeless. An exercise class has people of all shapes, including some chubby woman and a couple of young in-shape men, which suggests it's the only game in town.

Again the film returns to still shots of the town and its environs, silent and still. We don't even see cars driving around till half way through, though we do see cars sold second hand at a country fair where a trio plays country music. This is a quiet place, but Wiseman chooses to heighten the quiet rather than to seek out noise, or drama of even a mundane kind.

It is hard under the circumstances to guess what A.O. Scott meant by his remarks about this film in a NYFF preview the New York Times, to begin with his call it "patient and sublime." He wrote that in watching it one is "feeling assumptions gently and insistently undermined and replaced by an understanding that is all the more powerful for being nearly impossible to articulate." "Every cliché and talking point I’ve absorbed about the American heartland since the last presidential election was challenged," he goes on, "by Mr. Wiseman’s observations of democracy at work in a rural Midwestern town, though the name of the man who won that election is never mentioned." The observations of democracy at work are inconclusive. Those scenes are like any mundane city council or planning meeting in any American town, just a little more mundane and not perceptibly significant.

Yes, Wiseman is patient. "Sublime" seems a stretch.

Monrovia, Indiana, 143 mins., debuted at Venice, showing at five other festivals including Toronto, London, and the New York Film Festival. Watched in an online screener 10 Oct., its US theatrical release starts 26 Oct. 2018. Metascore 82.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 10-10-2018 at 05:58 PM.

-

WILDLIF (Paul Dano 2018)

PAUL DANO: WILDLIFE (2018)

CAREY MULLIGAN AND JAKE GYLLENHAAL IN WILDLIFE

Hard times in the West

For his directorial debut, the distinguished actor Paul Dano has delivered class all the way. It's a sterling novel adaptation from Richard Ford coauthored with Zoe Kazan, with first-rate thespian skills, and locations and a period rendered so beautifully every other shot is as if it was taken by William Eggleston, vacationing in Montana.

A little family seems forced into the role of losers by the dreamy Jerry Brinson (Jake Gyllenhaal), who has moved his wife Jeanette (Carey Mulligan), and son, Joe (Ed Oxenbould), now fourteen, more often than is comfortable. He gets fired from his job as a golf pro, really a glorified caddy, then when the club changes its mind, is too proud to go back. Fire is raging up over the hills somewhere, and after a time of desperation Jerry goes off with the fire-fighters for a dollar an hour till the fire is put out or snow comes. Joe and Jeannette are left to fend for themselves. The burden and focus are most on Joe, who watches his mother enter into a brief affair with a rich older man named Miller (Bill Camp), who was in theswimming class she's been teaching at the "Y." One of his businesses is a car dealership, and he sports a splendid new Cadillac in a pale color so subtle that, to paraphrase Fran Lebowitz, straight men would think it's white.

Joe gets a job, like Larry Clark, as a photographer's apprentice, and soon is doing portraits with an ancient view camera, but is forced into the role of passive observer in more ways than one. When the girl who's interested in him at school passes him a note in class, "Let's hang out after school," he sends back the one word, "can't." Dinner at Mr. Miller's house with his mother forces him to watch her flirt, dance, drink, and finally kiss, and it goes further later. Joe didn't want his dad to go away for an unspecified time, but he's compelled to support even shaky decisions from above. Unprepossessing and small, like Dano, Oxenbould is a subtle actor who makes passivity interesting, always saying the right thing, never more than enough, often seething but controlled. Everything is subtle: Miller isn't rapacious or icky. He's philosophical and contained, plays classical music. As Jeannette, Mulligan is desperate but never melodramatically so. Her utterances just seem unexpected and embarrassing.

When the snow comes and Jerry returns and finds out what's been going on, there's hell to pay, but that fire too is damped down before it becomes a dangerous conflagration. This would seem a stifled tale, were not the emotions so often on the edge of violence.

The scenery and cinematography with their evocations of classic American art photography are a continual delight. Reviewers who allude to Dano's "static camera setups and uncluttered frames" (Grierson in Screen Daily) and his "eye for elegant spare compositions" (Gleiberman in Variety)) are only underlining the same visual delight I've referred to in mentioning William Eggleston, one of the great transformative photographers of ordinary America. A feeling for period isn't strong, since in this isolated Great Falls, Montana setting, despite the signals of Cadillac, clothes, and broken TV, the mood could almost be drifting back to the Forties or Fifties. Miligan's performance is splendid, even though she looks a bit the worse for wear. Jake shouts a little: his big argument with Carey is more theatrical than cinematic. The cinematic may be the element Dano needs to learn to play up more. But he has so much easefully under his control Wildlife shows Paul Dano was meant to direct movies, and we can't wait to see his next one. It's a breeze, a movie that's memorable without ever grabbing our attention.

Wildlife, 105 mins., debuted at Sundance in Jan., then played in Critics Week at Cannes in May and in over two dozen festivals including Toronto, New York, and London. It opened in US theaters (limited) 19 Oct. after its NYFF play 30 Sept. It opens in France 19 Dec. under the title Une saison ardente. Metascore 80.

Screened for this review at Shattuck Cinemas, Berkeley 22 Nov. 2018.

ED OXENBOULD IN WILDLIFE. NOTICE THE BLUES.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-23-2018 at 12:31 AM.

-

THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS (Joel, Ethan Coeh 2018)

JOEL, ETHAN COEN: THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS (2018)

JAMES FRANCO IN THE "NEAR ALGODONES" EPISODE OF THE BALLAD OF BUSTER SCRUGGS

The Coens' Western sextet is finely crafted and nihilistic

In Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the Coen brothers' sequence of six short filmed Western tales made for Annapurna Television and then sold to Netflix, free of studio pressures, they have sculpted every segment with the precision and care of miniaturists. Though uneven and varied, they strike a balance, wielding oater clichés like hangings, saloons, nowhere towns, wagon trains and gunslingers in such an original and skillful way as to seem classic, justifying the film's inclusion in the 2018 New York Film Festival's elite Main Slate.

The narratives are dark and nihilistic. The degree and nature of the violence varies, always lodged comfortably in a dryly pleasing world where we can be secure in the knowledge that there is no hope. At first, with the titular opening segment starring Tim Blake Nelson as s a singing traveller in the Wild West who polishes off any and every opponent with alarming dispatch and nonpareil skill as a gunslinger, the extreme lawlessness of the times is paramount. In "Near Algodones," an incompetent bank robber (James Franco) escapes from being hanged, but that turns out to be false fortune.

Not everyone is dispatched with a bang. Witness "Meal Ticket," where an itinerant impresario (a grizzled Liam Neeson) finds that his novelty showpiece, an oratorical armless and legless Englishman (who recites poems by Shakespeare and Shelley and Lincoln's Gettysburg Address), now no longer a draw for rural audiences, has become like dead weight. A grim world indeed and a mutually dependent duo who alone would justify reviews hat compare this movie to Beckett.

A lonely gold prospector's lucky find isn't so lucky after all in "All Gold Canyon," an episode for its subtly dazzling depiction of western natural beauty and the pleasure of seeing how well Tom Waits can fill up a screen, but the deer and the owl have the last laugh. The brothers seem to have crafted every leaf, every drop of water and white hair on Wait's face and every crater on the pockmarked mug of the parasitical young villain who comes after him (Sam Dillon). Because it's mostly nature, the calculated artistry doesn't seem fussy. This tale is like a succinct version of "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre."

A certain delicacy, and a feminine point of view, enter the scene with "The Gal Who Got Rattled." Miss Alice Longabaugh (Zoe Kazan) mounts a wagon train with her short-lived and incompetent brother, Gilbert (Jefferson Mays), where the issues of debt and marital status are paramount. A way out appears when the handsome wagon driver Billy Knapp (Bill Heck, a find) grows interested. But a tragic mistake occurs during an attack by Indians. Like the other episodes, this ends with bitter irony. But it contains soft and touching moments..

People die aplenty in every episode of the Coens' collection, and any happy expectations of a positive outcome die with them. But no animals are harmed in the making. And, happily, no contractions are uttered, never an "isn't," "don't," or "wouldn't." A formality is maintained that simulates nineteenth-century speech. This quality is used effectively to convey Billy Knapp's and Miss Longabough's growing respect and affection for each other. The sequence of Arthur, Knapp's wagon leading partner, fighting attacking Indians as Miss Longabough looks helplessly on, is wonderful visually, closely resembling classic western paintings. The sweet sadness of this most admired of the segments lingers. This touching, complex episode counters any feeling that the Coens are merely indulging in tongue-in-cheek nihilism. This is also one of the triumphs of this first Coen brothers foray into digital imagery, and the production values, including the costumes and the wrangling of oxen in the wagon train, are very impressive, indicative of what a challenging film this was to make. The Coens have said "It wouldn't have hurt if we were younger" (they're 59 and 62).

Most of these episodes are stories the Coens themselves wrote over many years, except that "All Gold Canyon" is based on a Jack London tale, and "The Gal Who Got Rattled" comes from one by Stewart Edward White (1873-1946). We see the tales at the outset and conclusion of each as the pages of an old book - you can read them if you're fast enough - prefaced by an illustrative plate in an old fashioned style like that of Andrew Wyeth's father, N.C. Wyeth. This contributes to a solemn, staid, period flavor, a cozy distancing effect that tempers the Western violence.

The last episode, "The Mortal Remains," shot, in contrast, entirely on a sound stage, may evoke Tarantino's recent The Hateful Eight, since it focuses on a group of people in a stagecoach. Four men and one woman are the riders, two of the men bounty hunters, and one of them is Brendan Gleeson, the other Northern Irish actor Jonjo O’Neil. The Frenchman (Saul Rubinek), the prim and superior lady (Tyne Daly), and the grizzled trapper(Chelcie Ross ) fall to squabbling, till they are brought short by a haunting song sung by Gleeson. The images turn to monotone, and the meanings grow to grimly symbolic. Fort Morgan, the coach's destination, seems to be the end of the line in more ways than one. "Mortal Remains" seems like an unusually well-crafted "Twilight Zone" episode.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, 133 mins., debuted at Venice, winning the Golden Osella prize for best screenplay; it was shown at half a dozen other international festivals including New York, Busan, and London, then released on the internet in eight countries 16 Nov. 2018, also having limited initial theatrical showings at Landmark Theaters while showing on Netflix. Showing locally (San Francisco) at the Embarcadero and Shattuck Cinemas. Metascore 78. (Only seven Coens films rank higher on Metacritic.)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-27-2018 at 09:56 PM.

-

AT ETERNITY'S GATE (Julian Schnabel 2018)

JULIAN SCHNABEL: AT ETERNITY'S GATE (2018)

WILLEM DAFOE IN AT ETERNITY'S GATE

Once round the sunflowers again

We didn't need another Van Gogh biopic, as Mike D'angelo points out in his recent review, despite Anthony Lane's lengthy answer to the question, "Why Do Filmmakers Love Van Gogh?" It's not that the last word has been said about this important artist. We just need to move on from the frozen romantic image of the doomed, tragic, starving, mad (male) artist who dies young - to learn about other, not so famous, not so stereotypical, but much more modern ones. This we get in Florian Henckel von Donnersmark's new film, Never Look Away, partly based on Gerhard Richter, an original and still highly contemporary artistic genius whose life spanned key moments of the twentieth century, rising out of Nazism and the Cold War and a proliferation of modern art styles to forge his own original one(s) - an artist who, though this isn't covered in the film, is still alive and productive in his eighties. And this also is not an imitation of Richter's life but, I think, simply a good story.

But in his sympathy for Van Gogh we must acknowledge Julian Schnabel as an artist first and foremost himself and a notable one - something I don't think any of the previous "Vincent" biopic makers could lay claim to. The big paintings with plates stuck to them that made Schnabel famous in the Eighties were work that some scoffed at. Of course he sold plenty of him, unlike Van Gogh. But there is much emphasis on philistine scoffers here. And also much emphasis is put on the rave review Van Gogh received from Albert Aurier in Mercure de France, which is read at some length in voiceover by Louis Garrel.

What distinguishes Schnabel's new film is his sympathy for Van Gogh's twin passions - the passion for making paintings and the Christlike suffering of his life. After all the lead is played by Willem Dafoe, who played Christ in Scorsese's film. This Van Gogh even talks about Christ with a philistine priest at the mental hospital who thinks himself a judge of art (Mads Mikkelsen), and out in the field, he adopts a Christlike pose at one point. At Eternity's Gate vividly depicts the compulsion to be doing the work, no matter what, even when he is confined as mad. There is something quite moving in that, even though this ins't a fully satisfactory film. (Having a complete unknown, Louise Kugelberg, and a venerable veteran screenwriter, Jean-Claude Carrière, collaborate on the screenplay seems not to have helped.)

Other major players in the action are Van Gogh's art dealer younger brother Theo (Rupert Friend) and his colleague and friend for a time, Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac), whose clash with Vincent begins a long decline. Schnabel's direction doesn't seem outstanding here: nobody emerges as particularly distinctive, other than Dafoe, though Isaac looks pretty cool.

One can't help noticing that Schnabel has taken a very different tack here than in his second film, Basquiat, the treatment of an artist that was sympathetic, collegial, yet pleasingly, dry and comic. There Schnabel was dealing with a lot of people he actually had known firsthand himself. It was the art craze of the Eighties he was partly talking about. True, Jean-Michel qualifies as a tragic genius too, having died of an overdose at twenty-seven. But unfortunately for the romantic cliché, he had also become famous and rich, and the wonderful Jeffrey Wright plays him with a cool detachment that's quite the opposite of Willem Dafoe's appealing but unironic and over-explanatory version of Van Gogh.

There is so much wrong with At Eternity's Gate,, starting with D'Angelo's valid enough point: it's not necessary. After all there was a very engaging and original Van Gogh film just last year, Loving Vincent (La passion Van Gogh in the excellent French-language version). For all Schnabel's efforts - sometimes misguided - to evoke Van Gogh's eye, with shaky-cam, yellow filters, and luminous landscapes, last year's film, with its motion capture painted animation of paintings, is more remarkable and visually memorable, and it creates a quivering world that draws us in. Schnabel, the painter, works in a nice visual focus on Van Gogh's sculptural, impasto painting technique, objected to by Gauguin, who keeps telling him he should work slowly, work indoors, invent from his head, and lay the paint flatly, all things that were anathema to Vincent. But all this winds up feeling pretty familiar, despite its sincerity.

Appealingly, At Eternity's Gate feels somehow at times rather like a Sixties aventgardist film: the choppy structure, the piano score, the earnestness, even the big simple opening and closing titles show Schnabel maintaining contact with his original amateurist roots as a filmmaker. But At Eternity's Gate never merges into a real movie with fully alive scenes and richly interacting characters we can get lost into, like Pialat's 1991 film, my favorite, and the least corny of the Van Gogh biopic lot. Schnabel's film is just a series of vignettes, or stages of the Cross. One watches, ponders, and moves on to the next stage. (Some have suggested the film frequently stalls and has no rhythm.) Schnabel is more interested in odes to the beauty of light and philosophizing about art-making than recreating a world, telling a story, or building momentum.

The film's inappropriate, inaccurate treatment of language is a big wrong element that's damningly silly for this day and age. It consists of the unconvincing compromise of having villagers occasionally speak French, but Van Gogh nearly always speaking English, either with native speakers like Oscar Isaac as Paul Gauguin, or French guys speaking squeaky, weird English, like the great Niels Arestrop, wasted in a brief cameo as an insane ex soldier, or Matthieu Amalric, also wasted, seen for a minute as Van Gogh's friend Dr. Paul Gachet. This retro use of language is the more surprising since Schnabel boldly plunged into an all-French world for The Diving Bell and the Butterfly/Le scafandre et le papillon (NYFF 2007), probably his finest film, where he also plunges the viewer, with rude shock, into the nightmarish experience of locked-in syndrome.

Schnabel is trying much more wanly to lock us in, with the yellow-tinted images, blurred at the bottom, the wandering, jittery lens, the overlapping repeat dialogue to take us into Van Gogh's derangement. But this is part of an inconsistent conception of the man (just as, D'Angelo notes, the POV is inconsistent), because when Dafoe talks, he nearly always, even toward the end, sounds totally sensible and just damned nice. Dafoe is immensely appealing, and always watchable. He is a wonderful actor. But lacking is that necessary hard core otherness. He never ceases to seem like anything but Willem Dafoe, a guy who looks a lot like Van Gogh, playing Van Gogh.

At Eternity's Gate, 105 mins., debuted at Venice, where Dafoe received the acting award. Seven other international festivals, including the New York Film Festival where it was the Closing Night Film. Limited US release began 16 Nov. 2018. Screened for this review at Albany Twin, 7 Dec. 2018. Metascore 78.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-26-2018 at 09:06 AM.

-

IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK (Barry Jenkins 2018)

BARRY JENKINS: IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK (2018)

KIKI LAYNE AND STEPHAN JAMES IN IF BEALE STREET COULD TALK

A fraught, beautifully filmed Harlem love story from James Baldwin

It would be strange to speak of If Beale Street Could Talk as if it were a letdown after Moonlight, because in its way this new movie is impeccable. But Moonlight was very striking, won a raft of Oscars and nominations, and put Barry Jenkins on the map. He is also stepping into somewhat more "staid," or "hallowed" material in adapting a James Baldwin novel, a step back to a period (the Seventies, in Harlem). This is a tale - or more than a tale an experience - that is almost too beautiful, touching, and sweet to be true. The love story at the center of it seems idealized, the two lovers, Tish Rivers (Kiki Layne) and Alonzo 'Fonny' Hunt (Stephan James) too beautiful, innocent and true to be true. But maybe it's a fear of feeling that makes one pull back from the scenes in the film and not feel them till it's over. In fact in her piece in Cinema Scope about the film Sarah-tai Black says Baldwin doesn't really tell a love story but make us feel love: "Baldwin’s work is less expository than it is a feeling made concrete," Black wrote: "a translation of black consciousness, space, and time into words that are as generous as they are unambiguous." In Beale Street one has the sense of entering into a heady set of sensations, not of our time, but very much of the African American experience. Their intensity is almost too powerful to bear.

What is unfamiliar is so much of the black experience, which is enormous hope and passion and yet, conflict and ever-present disappointment. You realize plenty of ugliness is here. The "happy" ending of the film, after all, is itself a scene when Tish and their little son are visiting Fonny in prison and there's no way of knowing when he's going to be out. He's been out of prison only in flashback. And there is the bitter conflict in the two lovers' families, and the vindictive racist white cop (Ed Skrein), the fearful and hostile Hispanic woman, the hostility on the street, the constant economic hardship.

But there remains indeed something too pretty and too worshipful about this movie. As Variety's Peter Debruge wrote, what Jenkins has done here is "the equivalent of turn Allen Ginsberg’s 'Howl' into a Douglas Sirk movie (or put Alice Walker’s’ 'The Color Purple' through the Steven Spielberg filter." It's enchanting a lot of the time, but it's a little too dreamy, and too warm-toned and lovely to look upon to seem real. (Debruge points out the costumes are too pretty, and too distracting.) This lacks the rakish originality of Moonlight or the tartness of Jenkins' earlier Medicine for Melancholy.

The film centers around a child. After Fonny is incarcerated Tish discovers she is pregnant. She visits him and tells him and he greets this news with joy, even though he is sad that he cannot be there for the birth and the child. And this is where we learn about their love, and then there are scenes to show their first sex, and the moment when the baby was conceived. The big scene - it could be a gorgeous, vivid scene from a play - is the one where Fonny's parents are invited over and told, with Tish's parents present. All hell breaks loose because Fonny's mother (Aunjanue Ellis), who is Sanctified, rails against Tish as an evil woman and hails down almost a curse on her, and as a result she's physically attacked. The encounter ends horribly, revealing the enormous passions and hostilities that these people carry around with them. In the context established by this scene the purity of Fonny and Tish's love takes on an air of heroism.

Another memorable sequence is the one where the couple finds a place to live after a long search and reportedly many rejections, whenever the potential renter sets eyes on Fonny. They've found a young Jewish man who's willing, even glad, to rent them an empty industrial space where there is nothing around but sweatshops. Fonny and the man, Levy (Dave Franco, in a charming performance) do a little dance, pretending to lift up and load in a refrigerator and a stove, for in reality there are no appliances. It's a very touching, unusual scene. The place is like an artist's live-work space, which is appropriate, because Fonny is an aspiring sculptor. This is another way that this big, robust young man is delicate: he's sensitive about his art.

But the awfulness comes in the efforts to defend Fonny against the charge of rape that got him in prison. The lawyer tries, money is raised, and the rape victim being traced back to where she's fled, to Puerto Rico, Trish's mother Karen (Regina King) goes there and confronts an evil man, Pedrocito (a creepy Diego Luna). She gets to see the rape victim, but with disastrous results: she won't withdraw her dubious police lineup ID of Fonny and is so upset by the encounter that she disappears, and the case must be put on hold. The free-flowing flashbacks from different times underline the quality Black describes, that this is a "a translation of black consciousness, space, and time," not a story.

Jenkins has gotten rich performances from his cast. The two lovers repeatedly are photographed solo, full on, looking directly into the camera. Their openness and sweetness are overwhelming and again, almost hard to look at. The little boy, Kaden Byrd, who plays Alonso Junior, also looks straight into the camera with a mixture of boldness and guilelessness. He doesn't seem like an actor, has none of the usual young actor slickness. He's just like a little boy. He stumbles a little, his speech is a little halting. It's stunning.

Too sweet and too pretty Beale Street may be, but it has many fine moments and is clearly a labor of love by all concerned. It also left me moved.

If Beale Street Could Talk, 119 mins., debuted at Toronto, included in nine other festivals including New York. It opened in the US limited 14 Dec. 2018, wider on Christmas Day. Metascore 86.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-26-2018 at 09:08 AM.

-

HAPPY AS LAZZARO/LAZZARO FELICE (Alice Rohrwacher 2018)

ALICE ROHRWACHER: HAPPY AS LAZZARO/LAZZARO FELICE (2018)

ADRIANO TARDIOLO IN HAPPY AS LAZZARO

150% Italian

Exactly what Alice Rohrwacher is doing in this, her third feature (after Corpo Celeste in 2011 and The Wonders in 2014), isn't always entirely evident. She's clearly drawing on elements of both of those earlier works, and evoking classics of Italian cinema that include De Sica, Zavattini and the Taviani brothers. This movie is guaranteed 150% Italian in style and content, steeped in the tradition, yet unlike anything else: an original, whether we like it or not.

The director has her own story to tell. She weaves her own distinctive element of magic realism. Complicated things are happening, even if they feel unfocused through most of the first half. As in the last film, about bee keepers, a chaotic, but purposeful, rural agricultural life is going on, with other added layers of meaning.

At the center holding things together is the Lazzaro of the title. The untrained non-actor who plays him, Adriano Tardiolo, is a miracle of casting and wrangling. He moves and stands and looks exactly right at every point. He conveys grace and logic, a sense of stillness and inner peace. His mere presence gradually begins later in the film to compensate for the longeurs of the first half and the shocks of the second - for not all is well here; but there is that which arouses our forgiveness and momentary awe. Though she stumbles along the way - maybe to stumble is her way - Rohrwacher is also advancing along a path that leads somehow, mysteriously, toward Italian cinematic greatness.

The basic plot comes from a real Eighties news item. Somewhere explicitly called Inviolata (Italian writers think it, despite its isolation, perhaps not that far from Rome) fifty-some contadini, victims of a "grande inganno" (a great deception) are being forced by a wicked noblewoman called the Marchesa Alfonsino de Luna to farm tobacco in a slave-like sharecropper system whose illegality they're kept in the dark about. They called the Marchesa "the Queen of Cigarettes." There is a temporal dissonance no one notices. The corners of the images are curved, an "antiquing" effect, as if caressing the film's cinematic nostalgia. It's as if people not so long ago are walking in and out of a Neorealist film (by Visconti, De Santis, or Olmi), or the middle ages - one that meanders a little too much. Rohrwacher has a lively cinematic way of making the peasant world come to life, but not enough is actually happening, and the nostalgia is lazy sometimes.

In the foreground always is Lazzaro, a slightly frumpy, yet radiant figure, a man-boy so innocent he could be an idiot, except he understands orders and instantly (and happily and sweetly) responds to them, carry this, carry that, make me some coffee. These abject Italian peasants have Lazzaro to order around; he has no one. His face shines with sweat, ringed with curly beatific hair and bright happy innocent eyes that seem radiant. He is at once a wise fool and a secular saint. There is magic here.

But is Rohrwacher glorifying a crime? No, rather she is highlighting, if a bit laboriously, the essential contradiction described by Manohla Dargis in her Cannes report: this world is one that really is simultaneously both "emotionally sustaining" and "grossly exploitative."

Then the Marquesa's lean, stylish, bleach-blond and disaffected teenage son Tancredi (Luca Chikovani) hides away in the hills, taking the pliant Lazzaro with him to act as his accomplice in a faked kidnapping scheme to con his mother out of money. This fails, but Tancredi charms the simple boy with the fantasy he takes literally. He says since his father slept with many village girls, and Lazzaro doesn't know who his actual parents are, the two of them are probably "half-brothers." Even while hiding away, Tancredi keeps changing outfits. Lazzaro's never-changing pants and shirt go beyond poverty to convey a symbolic, magical status. His totem is the wolf. His name (Lazarus) will shortly take on its traditional meaning, and his embodiment of magic and transcendence will become definitive.

At midpoint, everything in the picture turns around. Lazzaro undergoes a transformation, while the whole local world, "Inviolata" no more, is exposed: police come, and its discovery leads to its annihilation. Time is disjointed, moving forward more for some than others, while Lazzaro changes not at all, but enters the new urban world the contadini have been transplanted to. Time passes. They now must steal and hustle to survive on the streets of Turin (or is it Milan? sequences were shot in both cities). Lazzaro arrives later, aged not a day. Offering to help, he's alternately seen as useless, and a unique resource. Carrying a symbolic slingshot, he seeks Tancredi. And he finds "Tancredi adulto" (Tommaso Ragno), an elegant, gray-haired man grown thicker and sweeter and now, with a touching, threadbare noblesse oblige, honoring the friendship with Lazzaro that in youth he seemed to mock.

Obviously the peasants aren't better off in the city to which their illusory "liberation" has taken them (not a very surprising insight). Their situation is only more desperate. They raise money selling objects from the Marchesa's estate that go for a pittance on the street. At least they got potatoes at home: now they're reduced to little bags of chips. Tancredi has a nice coat, but is reduced to nothing too. He invites Lazzaro to dinner, and the youth brings the whole little remaining gang, a sad and sorry pilgrimage.

This final sequence is far more consequential than anything in the first half. As it progresses, the aura of holiness around Lazzaro, out of his native element, grows more evident. Rohrbacher channels magic moments from a variety of classic Italian films. In the country, we felt the Taviani brothers' gentle, meandering presence. In the city it's a grimmer, speedier post-War Neorealism that takes hold. But Rohrwacher "transcends the tradition" in her own way - a tradition that includes Fellini, as it did in the very beginning of Corpo Celeste.

The magical realism surrounding the final sequence, when beautiful music dies in a cold cathedral dominated by mean nuns (the organ keys can make no sound) and flies out behind the evicted holy band of poor peasants (naughty and nice, they're all sanctified now) , and Lazzaro is quietly transfigured through a wolf that was his personal spirit - this is the director's own. As in the previous two films, images are constantly enhanced by the fine 16mm photography of French dp Hélène Louvart, edited by Nelly Quettier. Not everyone will have the patience or understanding for all this, but it is a remarkable amalgam, explaining how the scenario, its vision and its patient realization, could have won a big award at Cannes.

Happy As Lazzaro/Lazzaro felice, 125 mins., debuted in Competition at Cannes, where it won the Best Screenplay award, and was shown at nearly two dozen other international festivals, including Munich, New York, and London, winning nearly a dozen other awards and nominations. US theatrical release 30 Nov. 2018, also on Netflix. Metascore 86. Watched on Netflix for this review 26 Dec. 2018.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-26-2019 at 10:08 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

NYTimes 21 Mar. 2018

NYTimes 21 Mar. 2018

Bookmarks