-

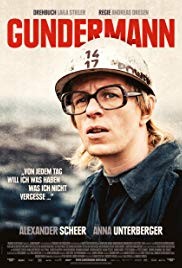

GUNDERMANN (Andreas Dresen 2018)

ANDREAS DRESEN: GUNDERMANN (2018)

ALEXANDER SCHEER IN GUNDERMANN

Portrait of a complicated man

Gerhard Gundermann, "Der singende Baggerfahre," the "singing dredge driver," is an anthemic East German composer-performer of the 1980's and 1990's - known for "his clever, often melancholy lyrics imbued with social commentary" - with a past marred by association with the Stasi. He survived this stain when it emerged, only to die suddenly and unexpectedly at only 43, in 1998. A cantankerous and complex figure even young Germans may not have heard of, Gundermann proves worthy of the biopic he gets here from German director Andreas Dresen and regular collaborator Laila Stieler (for the script). The story meanders a bit, but the better thus to illustrate its subject's many good songs (sung by Scheer) and equally numerous contradictions. Alexander Scheer, one of Germany's best actors, plays the lead. Look at photos and films and you'll see the uncanny resemblance he and the makeup crew have created. Anna Unterberger is irresistibly appealing as the love of Gundermann's life, Conny, and there are other notable cast members in this film that's very much an ensemble piece while totally revolving around its protagonist. Patience is rewarded by a sense of this film's loyalty to and eloquence about its unique, intractable and curiously admirable subject.

What's not to like? Well, Gundermann, who worked in an open coal mine even after he'd become pretty famous, never tried to please anybody. Not his father, from whom he became estranged. Not the bosses of the mine, whom he pissed off. Not the communist party, to which he sincerely meant to be loyal, but which eventually expelled him for his outspoken criticisms. And his songs are frank and love life but are frequently sad. He did sing a celebratory song with Conny about their marriage, and the songs, even when downbeat, can be anthems.

Conny was in Gundermann's band (one thing the movie leaves out is an earlier gaudy rock period), and she was married to another band member who was his good friend. Gundermann and Conny finally acknowledged the relationship. Gundermann moved in with her and her kids. Her husband moved into Gundermann's place. "I should hit you," the friend says, as he moves out, and that goes for a lot of times. How did the kids take that? Well, Gundermann was great with kids, and saves a hedgehog on the highway early on. (The hedgehog doesn't make it, but gets a tender burial.)

My favorite character is Helga (Eva Weißenborn), the craggy old dredge driver who's done the job forever and who appreciates Gundermann's stubborn intractability. And what? His loyalty? But he has betrayed many people, reporting, for instance, on folks who want to escape to the West.

The film's shifts back and forth in time are signaled by the different glasses Gundermann wore, big tortoise shell ones early on and aviator-style wire models in the latter years, though in truth he doesn't seem a very different man - except that he was, of course. For all its time-shifts, the focus is on the key period of Gundermann's fame - and his infamy. He was an unofficial collaborator with the infamous GDR intelligence service known as the Stasi from 1976 to 1984. But this time of his life isn't painstakingly illustrated, as in Von Donnersmarks's The Lives of Others. That is not the interest here, but the aftermath. We see his half-forgotten Stasi years as a thing that haunts him; that he has forceably forgotten; as a fact he must acknowledge after the fall of the Wall, the GDR revolution, the Gauck Commission, and the discussions of Offenders and Victims.

He was both, but his Victim file has disappeared, as he learns from the Gauck Commission, in a typically very personal scene with one of its functionaries. But it may have been small. His Offender file he eventually gets access to through a journalist - they alone could get such access - is boxes and boxes-full. An angry young woman journalist brings them to him and Conny, another personal scene. (The writing may be a bit simplistic here, but it still works.)

In numerous scenes of composition, rehearsal, and performance, the film tips the balance back toward the reason for this movie: it's about a notable artist. The filmmakers and performers convey the soulful honesty of Gundermann's songs, even if something is inevitably lost if one doesn't know German. But what truly impresses is the intractable, unique ugly-beautiful bravery of the contradictory man.

The heart of the film comes when the Stasi evils are being revealed and Gundermann must face up to what he did, and does. He acknowledges that he is ashamed, also surprised at the extent of his "reportage." He can't go on claiming it was only complaining about conditions at the mine. He can never apologize. It's not in his nature. But he confesses, to each of his audiences in turn. He talks about it to Conny, who stays firmly loyal. He tells his coworkers. He tells his band. Slowly, they decide to go on performing with him. Finally, in the film's most memorable scene, which creates a feeling hard to put into words. In a big public performance, he tells his audience, which at first is shocked and silent. Then the band plays, Gundermann sings, and they applaud. Lesser, or more commercial, filmmakers might make this into a corny scene. Here it simply captures the moving strangeness of the real.

Gundermann, 128 mins., premiered in Gundermann's town of longtime residence, Hoyerswerda, in Saxony in Aug. 2018, and showed at Tromso (Norway). It was screened for this review as part of the 2019 San Francisco Berlin & Beyond series.

Berlin & Beyond showtime:

Sun. March 10, 2019 6:00 p.m.

Castro Theatre, San Francisco

North American Premiere

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-23-2019 at 10:51 AM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks