-

FUKUSHIMA 50 (Setsurō Wakamatsu, 2020)

SETSURŌ WAKAMATSU: FUKUSHIMA 50/ フクシマ50 (2020)

STILL FROM FUKUSHIMA 50

Good but not great film about the Japanese nuclear disaster

This is the first big budget, big name film about Japan's 2011 earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. It stars Ken Watanabe and Koichi Sato and has plenty of excitement. But as more than one commentator has noted, it "lacks nuance" and is timid ("earnest, if somewhat toothless," said James Marsh in SCMP being unwilling to point accusing fingers for something that like the other big ones, Three Mile Island and Chernobyl (the latter having its own superb for-television mini-series), were rife with human error. As Anthony Kao has written in Cinema Escapist, its timidity about responsibility will probably mean this film won't ever get the international audience the dramatically more sophisticated Chernobyl mini-series received. But that doesn't keep it from being "immensely valuable" and "intriguing' from the historical point of view. But artistically this reads as lightweight compared to the superb miniseries by Craig Mazin, Chernobyl.

The focus is on the nuclear plant workers who remained - initially fifty, hence the title - to minimize the damage. The main source is a 2012 book by Ryusho Kadota commpiliing ninety interviews with all levels from basic plant workers to PM Naoto Kan, and depicts a race against time to minimize escape of radiation while the team was able.

A reflection of the reticence is that all the workers are fictional, including shift supervisor Toshio Izaki (Koichi Sato). One exception is Masao Yoshida (Ken Watanabe), the impressively down-to-earth and energetic site superintendent and emergency response team leader. Mark Shilling, the veteran Japan Times reviewer, says Yoshida was "too famous to fictionalize" because he was the public face of the response team even internationally. The original of Izaki also passed away seven years ago from a cancer judged to be of other origins, and a memorial to him is built into this film.

This film doesn't point fingers, and is framed in shades of gray. But it has its dramatic high point; Yoshida's decision to go against the instructions of Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) officials to stop cooling the damaged reactors with sea water because they feared the equipment would be ruined. If he hadn't continued to cool the reactors the center of the country would have become uninhabitable. TEPCO is a pushover compared to the fearsome opponent represented by the Soviet Union''s Central Committee in Chernobyl. But at least Wakamatsu's film makes no bones about the profit-first focus of TEPCO in the face of a massive human disaster. The film also isn't afraid to show how confused and panicked the rank and file workers were when confronted by the chaotic events surrounding them.

The film also does a good job of depicting the initial earthquake and then the resulting tsunami that washed over the power plant's coastal defense walls flooding the main structures and knocking out the backup generators required to cool the reactor cores. It also fills in some US responses both bad and good - the callous reaction from the Obama administration; the admirable humanitarian relief effort mounted by an American air force general.

What I remember of the Chernobyl mini-series are the relationships between people, though: the conflicts and altering power structure as events were referred to higher up and the prolonged disaster action action was carried out. Not the rush of action so much as the long slow creepy sense of danger from radiation. Not sure there is quite an equivalent here for all that. Perspective is provided here of responses at the Prime Minister's office and a US military base. (Notably, the PM's helicoptering over the Fukushima station caused a delay in the recovery operation.) But the quality of the writing is less impressive than the sense of reproducing the event and its army of brave men of action, "valiant warriors," as Anthony Kao calls them.

The Japanese and the Soviets may have something in common besides having hosted the two worst nuclear disasters - level seven on the International Nuclear Event Scale: having a culture of unwillingness to find anyone responsible.

Fukushima 50 / フクシマ , 122 mins., opened Mar. 6 in Japan, in June in Vietnam and Hong Kong. In July it had internet release in Poland, DVD and Blu-ray in the Netherlands. In the US it has internet release as part of the July 17-30, 2020 Japan Cuts, for which it screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-26-2020 at 06:05 PM.

-

THE MURDERS OF OISO ( Takuya Misawa 2019)

TAKUYA MISAWA: THE MURDERS OF OISO /ある殺人、落葉のころに (2019)

TRAILER

With a friend like Kazuya. . . a stylish slow-burner

The Murders of Oiso is actually the Japan-set collaboration of three 2015 alumni of the Busan Festival's Asian Film Academy, Takuya Misawa, Fei Pang Wong and Cyrus Tang, with Misawa in charge and working with a Hong Kong film crew including cinematographer Timliu Liu.. It's a slow-burner character study that's at once very Japanese and reminiscent of a 19th-century long short story. In cinematic terms the collaborators could have been thinking of Hou Hsiau-hsien's classic The Boys from Fengkuei, or equally of Fellini's thirty-years-earlier I Vitelloni. (In an interview he mentions only wanting to express, obliquely, social and gender issues.)

The look of the film, with its wide aspect ratio, autumnal colors, and yellow filters, is quite distinctive and appealing - and delicately distancing, appropriately because all this is as recollected, sketched in words on paper, by a woman involved and Misawa himself. The opening shots are of boys in gymn class, figures moving back and forth intentionally paralleled to flocks of birds. The cutting skips gleefully from one location to another and the camera cuts off some identifying features, both camerawork and editing at times willfully withholding in style, declaring the inbred nature of the action.

This version of dissolute young men revolves around three slacker locals, Shun (Shun (Koji Moriya), Tomoki (Haya Nakazaki), and Eita (Shugo Nagashima) who work for a construction company and hang out with the evidently obnoxious Kazuya (Yusaku Mori), who's their age and drinks and smokes and plays cards with them yet has ceased to consider himself their equal because, while impecunious at the moment, he will inherit the company. And that comes sooner than expected. The stage is the small coastal town, Shonan, Oiso in Kanagawa Prefecture. They all live where they were born and raised, but their friendship is altered by the death of their basketball coach at school, who is Kazuya's uncle, and is found dead. Shun is attracted to Senri, the widow of his teacher. Tomoki shows a relentless commitment to Shun's behavior. Kazuya decides to break the law because he needs to raise money for his family. he tall, shaggy-haired Eita seems to owe some kind of debt to Kazuya. The presence of Eita's girlfriend, Saki (Ena Koshino), puts the others continually ill at ease, particularly Kazuya.

Eventually on a long night of drinking in the storage space where the boys hang out, Eita unwittingly puts his fiancee at risk with Kazuya. And that is when all the tension and unease become intense. Family and friends, the intimate relationships that have been build up are flipped; awareness of the outside world has made everything unnatural now. At the end of the story, it seems as if the curtain is falling on a tragedy.

As online critic Selina Lee bluntly puts it, Murders of Oiso is a story of "pent-up aggression "and "toxic masculine friendship." The vitelloni-style idleness is made confusing by the fact that they're working, but all the focus is on the hanging-out and nearly meaningless chatter - despite sketching in of all kinds of events in the larger local world. The action's main space is always the small, garage-like storage space with a pull-down corrugated door where one of the boys, Tomoko, sleeps and the others come to hang out.

Lee further notes that throughout the film "bodies are found" and "family secrets are revealed" but "in Misawa's controlled hand" these events that might normally be considered "major plot points" (of a noirish nature) are "greeted with impassive shrugs." And the visual is never forgotten, as a sense of aesthetic detachment: there are "frequent shots of verdant ginko leaves, radiating sunshine" (with much emphasis in suites of images upon yellow objects), and "breaking waves" that "bear witness to everything that's concealed from the audience."

The way the apparent tragedy is resolved is rather facile (the title is a tease), and the film leaves a tad too many lacunae. But along with the youthfulness of the filmmaking there is a keen sense of the visual, a feeling for tense small town claustrophobia, and a play with character that's interesting in the way it considers the interplay of class and personality.

In an interview Misawa admits he's uncertain if the audience will get what he was trying to do in The Murders of Oiso. But one feels the filmmaker's passion, enhanced by the skillful Hong Kong crew and the restrained score performed by Eiji Iwamoto, which are pro all the way.

The Murders of Oiso, 79 mins., debuted at Busan Oct. 2019, also showed at South Taiwan, two Hong Kong festivals, and Osaka. Theatrical release in Hong Kong in June 2020. Screened for this review as part of the all-online pandemic 2020 edition of New York Japan Cuts.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-27-2020 at 05:38 PM.

-

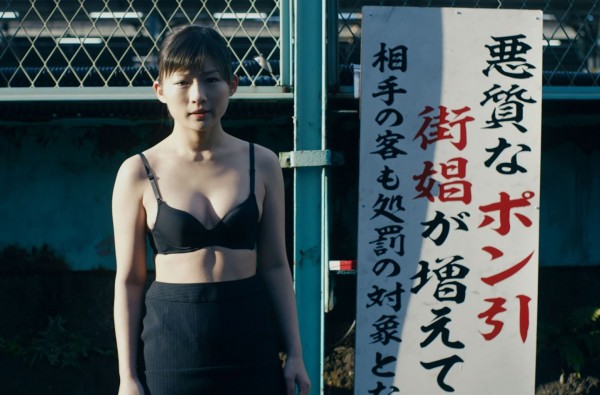

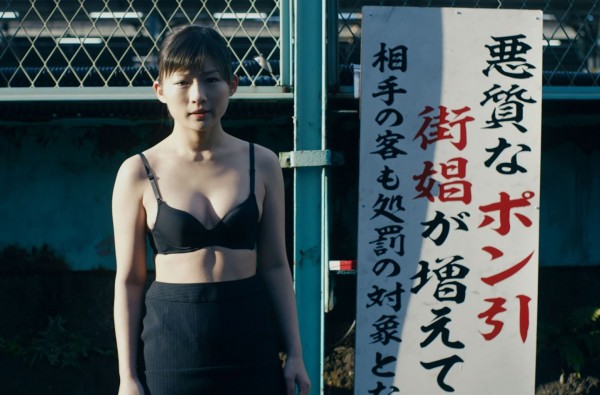

LIFE: UNTITLED タイトル、拒絶 (Kana Yamada 2019)

KANA YAMADA: LIFE: UNTITLED タイトル、拒絶 (2019)

Life in a call girl HQ

This feature about life surrounding a contemporary Tokyo dispatching headquarters for call girls may be contrasted, sharply, with Bertrand Bonello's moody, decadent Apollonide, about a sad but grand and beautiful Paris brothel at the end of the 19th century when they were in grand decline. This environment is cheerful, energetic, but makeshift, giddily energetic yet depressing.

The apartment's just a jumble, and the operation seems haphazard. Who's in charge? Yamada has trouble presenting this as a working business. But then prostitution is a funny kind of business, isn't it? In the first scene (after the one introducing the voice of the piece, Kano (Sairi Ito), who's too outspoken to be a sex worker but stays on as a dispatcher and wrangler) we see that three of the girls get fed up and take off for the day in the middle of the afternoon, leaving Kano in a potential bind. Before that, they were laughing riotously. They like to joke about the absurd behavior of the johns. One young woman, a self-declared "slut" from childhood, is so emotionally damaged she giggles all the time, and obsessively watches TV.

LIfe: Untitled is adapted from a play, the director's, and it shows in the restriction of most of the action to one big room, to the sharply contrasted personality types and the "dramatic" events, though with no overriding plot-line discernible. As in Apollonide, there is a plethora of characters and one spends the movie trying to get them all straight. In a blatantly stagey moment, a girl with glasses who's always scribbling in a notebook gets a call from her mother that her father has died in a hospital, and precipitously goes off on leave.

There is Riyu (Tomoko Nozaki), the top call girl, who says everybody here is a failure in society. Mahiru (Yuri Tsunematsu) is so in demand, an older woman, Shiho (Reiko Kataoka), is substituted. Atsuko (Aimi Satsukawa) is full of anger or hysteria in her every line. There are several men. The bleach-haired Ryota (Syunsuke Tanaka, who overacts horribly), is the self-hating driver. He has had sex when they were both drunk with the pathetic Kyoko (Kokoro Morita), who thinks this means love and has knitted him a gaudy scarf, and he yells and whines at her: a marriage made in heaven. In charge is Yamashita, who, like Ryota, has had sex with the girls, sometimes for pay, sometimes for free, and regrets it. He runs the business for an old man, Denden. They talk of moving this HQ to a new and better location. Hagio is another male employee, with little screen time, a call boy.

One reviewer says Yamada's women all "take their particular kinds of revenge against a misogynistic and oppressive society ruled by male violence." Really? Mostly this world just seems hysterical, chaotic, and full of drama queens - of both sexes. Another, wiser review says "Life: Untitled is an explosive chamber piece of psychological deterioration.." That's true enough. But if only the psychological deterioration were not so obviously play-acting. Josh, on Letterboxd, accurately says, "This movie needs to take it down several notches.."

Life: Untitled タイトル、拒絶, 97 mins. premiered Oct. 2019 at Tokyo.

It was screened for this review as part of the 2020 all online New York Japan Cuts.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-27-2020 at 10:18 PM.

-

ROAR /轟音 Ryō Katayama 2020)

RYŌ KATAYAMA: ROAR 轟音 (2020)

RYŌ KATAYAMA IN ROAR

A world of converging menace and violence

Roar is the strange, disturbing writing and directing debut (with an enigmatic lead performance thrown in) by Ryō Katayama, who arrives with twelve years of film, TV, and video acting credits. Set in the somewhat desolate-seeming Fukui City, on Japan's north central coast, this pursues two unrelated narratives that converge briefly and violently at the end. There is repetitive violence, menace, emotional disconnection here, and it's underlined by shaky camera, some sudden extreme closeups and a series of initial attention-grabbing POV shots; and with a judicious use of ambient sound, with not much music. The noises and earthquake-like shaking in early scenes excite one and get one's attention. The initial effect is delicious, a nice palate cleanser after mild, correct Japan Cuts films like Extro, Voices in the Wind, or Fukushima 50. What follows is somewhat repetitive, taking us to the world not of noir but modern alienation, corruption of money, the act gratuite. The action remains edgy and menacing enough to hold one's attention, and everything moves toward increasing tension and the final climax.

The first of the two parallel storylines follows a lost, disturbed young man, the other a popular local radio announcer bothered by her sexually predatory boss. The second storyline is a slow burner; the first is chaotic and disturbing from the start. Reacting to a horrendous crime committed by his older brother Tadashi (who goes to jail for murder), Makoto (Ryo Anraku) is about to commit suicide himself but then finds another solution: he throws away his phone, ringing with a call from his mom, and runs away. He needs to get away from this family. Through odd, violent circumstances, aimlessly wandering back alleys of the downtown, Makoto begins shadowing a silent, shaggy-haired vagrant, Manabu (Katayama himself). They sleep together on the tatami mat floor of a storage room where brown paper bags mount up, and live off of packaged sandwiches. Katayama underlines the animalistic situation. When they wake up, they tear open a wrapped sandwich or pastry and wolf it down. Manabu does muggings for hire. They're assigned by the same man, who shows Manubu a photo, then a uniform envelope. Manubu goes and beats up the guy, with the client watching, who usually has to call Manobu off.

There is terrible unspecified sorrow lurking here: in one scene, Manubu prays and sets out flowers neatly on an elaborate grave. Always, always, Makoto is standing in the background; eventually he starts trying to find out why Manubu pursues this life of violence and to stop him, but he never succeeds.

In the other storyline, Hiromi (Mie Ota does her thing as a youngish, single, popular radio talk show person whose admirers regularly call in with inane fan questions. She is trapped in a lackluster affair with her unattractive, married boss at the station, Nomura (Shoji Omiya) whom she doesn't like, but seems unable to ward off. When Hitomi's girlfriend and former assistant Miyuko (Mari Kishi) comes visiting from Tokyo she arranges for Hitomi to meet a guy who's nice, handsome, and a fan - and he doesn't have to be imported: he lives right here in Fukui City. Following scenes pursue this tentative, restrained courtship as Hiromi and Kentaro (Takuya Nakayama) date and in a very restrained manner, get close. Nomura's boorish intrusions continue. Eventually, he finds out she is seeing this handsome younger man.

And this alternates with the continuously strange life of the boy, Makoto, and the lean, sad-looking professional strongman, Manabu. In one strangely intimate scene Makoto watches as Manabu tries to cut his own hair without a mirror, and moves over and begins to pull off tufts of it and cut them for him. Once Makoto apologizes for eating Manabu's pastry. He will only speak to him in the climactic final moments. Cross-cutting brings together two violent final scenes when Hiromi strikes back just as Manabu's latest attack is taken over by Madoto, who has been begging him to stop, but in helplessness joins in with a vengeance.

This can be seen as a kind of anonymous revenge flick, since most of the men paying to have somebody beaten up by Manabu must want revenge. Hiromi, had she known, might have arranged to have Manabu beat up Nomura. Unfortunately, Nomura beats her to it at a fatal time. This does not end well. I don't think Katayama is telling a very good story. A pointless subplot involving Mayuko belonged on the cutting room floor. He may intend, as online critic John Berra says, to "challenge deeply entrenched cultural codes or rigid power structures," but this seems too pulpy and extreme to communicate to the audience for such editorializing. What he is clearly good at is manipulating the material in a way that's experimental and so deliciously cinematic one doesn't care, as one doesn't with a pulpy B-movie, whether the material is tasteful - or even makes sense.

Roar 轟音k 99 mins.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-28-2020 at 06:15 PM.

-

BOOK-PAPER-SCISSORS /つつんで、ひらいて (Nanako Hirose, 2019)

NANAKO HIROSE: BOOK-PAPER-SCISSORS / つつんで、ひらいて [Pinch me, open me] (2019)

NOBUYOSHI KIKUCHI AT HIS WORK TABLE IN BOOK-PAPER-SCISSORS

A designer of books who does it the old way

As you all know, in Japan uniquely they can declare a person a "natural treasure." Nobuyoshi Kikuchi, now seventy-seven, may deserve that status - if people still care about books. Sometimes the digital world seems to have forgotten them. To meet a revered book designer is to remember the thing-ness of books, their beauty as objects to be held in one's hands. Here we meet the process, the preparing (his preferred word) of the book, its physicality and its art.

Kikuchi is revered, and he, and the blurb, speak of how many books he has designed (they differ; they say fifteen thousand, he says ten), but though he is still at work, his method is antiquated and has long been so. He designs book jackets' physical layout not unlike the way I saw them being designed at Turk & Reinfeld in New York five decades ago. Like those book jacket designers, but with much more attention to the whole book, a focus on literary works, and a profounder study of the content, he does it all by hand, moving characters around with tweezers, tacking them dow with tape or glue. (They appear to be all, or nearly all, "abstract," without images, like a mosque.) A longtime woman collaborator in the next room (who doesn't always agree) changes the size of the images electronically. A younger designer, his apprentice Isao Mitobe, is at his computer, and says what he does on it to him is "drawing." Kikuchi's work station is simple, with one light but a big window. Outside are beautiful plants that he says grew up from seeds plucked and dropped by birds and fertilized by their droppings. It's wandered over by several ornamental cats.

The essence of this documentary is seeing Kukuchi hold up books he has designed, or the mockups of them and talking about them. When he encountered Tetsuro Komai's design for the Japanese edition of Maurice Blanchot's The Space of Literature, wit its flat drypoint images and the gold lettering centered upon them, it was like love, a revelation he still comes back to, fifty years later, and talks about. He explains the feel of a paper (paper itself an art the Japanese excel at), "like a lover's skin," the choice of a color, how he got a certain shade of red by printing it over white, the challenge he sees in having to include a barcode. He reads the most important part of the book and absorbs it. He thinks it out. For a bar across a book on Christianity he chose a certain brown to suggest the wood of the cross.

Kikuchi himself has the mellowness of polished wood. But in his youth he dropped out of art school because he had his own ideas on design, and he points out a jacket with characters all at an angle that shocked the printers. He still seeks to surprise. A bookman points out at times he has "challenged the expectations of bookshops and distribution" with designs that were "boldly defiant" and pointed to his opposition to the way print was going. A poet who's worked with the designer says letterpress - hand type-setting, was wiped out by the Great Earthquake. It destroyed all the small presses where letterpress was still done. Will books in the future only be read? he asks, puffing on a pipe and smiling. Bookshops still survive, at least, he adds, "thought we will never know for how long."

All this is about caring about the physical book. There is a sense of life enjoyed through savoring good things aesthetically. With an old friend he celebrates at a favorite ramen shop surrounded by warm wood. At home, as at his favorite cafe, which started when he went frelance and he considers an extension of his office, he enjoys good coffee he has made lovingly with beans he has ground by hand and poured into an exquisite thin white china cup, a masterpiece of another art the Japanese excel at, ceramics. Everything is thought out, savored, contemplated. Relaxing, he winds up a handsome, carefully preserved gramophone and plays a tango. Out the window is a balcony on the sea and the horizon shows small sailboats. Inside the walls are dense with antique baked pots.

Kakuchi does not pose as a man of wisdom. After designing all those books, he says, he only feels "empty." "I've always talked," he says, "about how literature was a tool for nurturing the mind. However, the more I design these books, the more empty I become...After achieving all this knowledge, one only gets confused."

But when, later in the film, Kikuchi is designing a new edition of Blanchot's The Space of Literature, he's excited. He hugs the paper he's chosen that he says is "better than the samples," rubbing it against his face and saying, "Don't tell!" He speaks of Blanchot dating Marguerite Duras in '68 and says the paper is Duras' skin, the color of her lingerie. He's nuts, but it's quite wonderful, and we begin to love the man at last. After the three volumes are done, he is let down and says he will never be so excited again; there is no "next level" he can go to after this.

This documentary at any rate is directed with a sure and steady and modest hand - and with love, and its patience is rewarded. I was reminded of Nicolas Philibert's lovely doc about an elementary school class in the French alps, the reward for several years of patient, loving observation. This film, though it's less detached and more interrogatory, and sometimes engages with Kikuchi, is similarly the result of a three-year passion project by Hirokazu Kore-eda protege Nanako Hirose, whose late father was himself a book designer born in Kanagawa, where Kakuchi lives and works (in Kamakura). This has Kakuchi's contemplative, patient style too in a work that's primarily for "design enthusiasts and bibliophiles." But you don't have to be a "bibliophile" to love books or enjoy seeing them considered as objects of a designer's art. Artists and makers of artist books might also want to look.

Book-Paper-Scissors /つつんで、ひらいて ("Pinch Me, Open me"), 94 mins., Debuted at Busan Oct. 2019 and was released in Japan in December; it has had online releases, nicluding at Japan Cuts 2020 (July 17-30), as part of which it was screened for this review.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-29-2020 at 12:39 AM.

-

MRS. NOISY (Chihiro Amano 2019)

CHIHIRO AMANO: MRS. NOISY ミセス・ノイズィ (Misesu Noizi) (2019)

YUKIO SHINOHARA, YOKO OHTAKA IN MR. NOISY

An annnoying neighbor inspires - eventually - a successful book

Writer-director Chihiro Amano's dramady partly from a news story is her fifth feature; several others were based on manga. The result, full of material about the dangers of social media and the fickleness of the reading public, is interesting for its female Japanese angle these matters.

Maki Yoshioka (Yukiko Shinohara) is trying to juggle the roles of writer, wife, and mother. Under the pen name of Rei Mizusawa, she published a much admired and award-winning novel some time before her now six-year-old daughter Nako (Chise Niitsu) was born. Not surprisingly, perhaps, motherhood has derailed rather than inspired the writing, and her publisher rejects her latest stuff, saying the characters lack depth. Moving into a new apartment in a large block of drab flats (or "danchi") with her husband and Nako, Maki tries again. But she has just as much trouble, Nako is still demanding, and there is a new obstacle, the soon-to-be eponymous Mrs. Noisy.

This is Miwako Wakata (Yoko Ootaka),the neighbor who starts one day very early beating violently and long on a futon draped over the balcony, a procedure that soon becomes a habit. Later she also sings, or when challenged on her singing by Maki, cranks up a ghetto blaster. And there's another provocation. One day Nako, who says her mother is "always working" wanders off and is rescued by Miwako and her husband, and when they return her hours later Maki hits the roof. (Maki's husband is a rather shadowy figure in the story, away at work, present mostly to try to calm Maki down, memorable chiefly for drinking directly from a wine bottle when they first move and and have no glasses unpacked.)

The resulting fracas between the two women neighbors causes such hostility that the futon-beating and over-the-balcony tussling gets on social media, and eventually TV. A replay of events from the nighbors' POV, however, shows Miwako beats the futon to soothe her husband, who suffers from delusions. Replaying the time they spent with Nako we learn they rescued her, and cleaned up the mess she had made of her face with lipstick; a bath is required. It is telegraphed to us that this couple have lost a young son, hence the toys they entertain Nako with, and the need to play with her. They were late returning her because all fell asleep. It was all very innocent, sweet, and sad.

The film follows Miwako's life sorting cucumbers for a farm, as well as Maki's dealings with publishers. It's Maki's cousin, a mophead busybody a skateboard, who gets Maki's work going again, simply by urging her to write about the noisy neighbor. This leads to a new contract for Maki to do a serial for a magazine. It's so successful there's soon also a contract promised with a more prestigious publisher. But a young woman who knows more about books than the cousin tells him these serial articles are just as superficial as Maki's recent, unsuccessful work.

What is needed is more turmoil. And Amano gives us that, with the drama of threatened lawsuits, uneasy manageresses, and so much scandal and violence that contracts are canceled or not offered after all. There is an attempted suicide, a reconciliation, and very quickly - you can't show writers writing; it's not entertaining - Maki comes up with a book version of all this that achieves depth in the characters, has people laughing and crying, and makes her a hit writer again.

I'm not sure I really believed the older couple, though Yoko Ootaka, as the futon-beater, who seems to be without previous film acting experience, has a solid, weathered authenticity the others lack. It was also hard to see the hilarity of the squabbling women depicted in multiple media stories. Maybe you needed to read all the type flashing across the screen as the Japanese like to have, or to be familiar with the hazards of "danchi" living. If you know of lots of problems of this kind, an example that goes a little over the top might be fun for rioutous collective laughs. And perhaps for the right audience, this movie works the same way.

Mrs. Noisy / ミセス・ノイズィ, 106 mins., was screened for this review as part of the July 17-30 all-virtual 2020 Japan cuts.

Mrs. Noisy ミセス・ノイズィ 106 min.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-30-2020 at 11:34 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks