-

NY ASIAN FILM FESTIVAL Aug. 28-Sept. 12, 2020 online

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-11-2021 at 12:57 PM.

-

BENEATH THE SHADOW 影裏(Ohtomo Keishi, 2019)

OHTOMO KEISHI: BENEATH THE SHADOW 影裏 (2019)

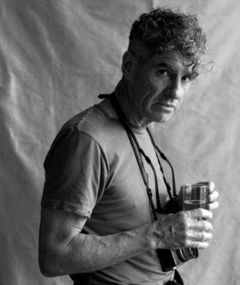

ANANO GO IN BENEATH THE SHADOW

Friend

The blockbuster director of the romantic manga sword fighter Rurouni Kenshin films here explores his contemplative side with an arthouse film based on a prizewinning contemporary novel. It is the story of a strange, haunting friendship. Shuichi Konno (Anano Go)is a delicate-looking young man of thirty who's transferred to northeastern Japan, Morioka (Iwate), by his company. He seems to have been excited, and then, lonely. Someone else comes to work there, Norihiro Hiasa (Ryûhei Matsuda of The Sythian Lamb, NYAFF 2018), who latches onto Konno, gets drunk with him in his apartment, takes him fishing, later, even camping. We know there is something, well, fishy about Hiasa, but we also believe in Konno's fascination, need, even, it seems one night, desire, in this moody piece of minimalism.

The devil is in the details. And Ryûhei Matsuda, who seems more confident, even aggressive, even hostile with Konno, seems devilish. Anano Go is a bit of a sex object at first, the camera caressing his butt and crotch in jockey shorts in opening scene repeatedly. The "friendship" between Konno and Hiasa seems a bit suspicious, or maybe Konno is just so lonely. But no - Kazuya comes for a visit, and it emerges that in Tokyo Konno had a relationship, commemorated by a very long hug, with someone who has become a trans female. But the details are of the fish, how to put a worm on a hook, then gang hooks, Hiasa's little chat about the cycle of nature - "moss loves fallen trees" - and his story about the pomegranate tree (an image picked up later) in his yard growing up.

This is yet another Japanese film that weaves in the Fukushima event. Iwate, where this mostly transpires, was affected by the earthquake, I understand. But first, there is Hiasa's sudden disappearance from work, followed by his surprise reappearance later selling shares in a suspicious mutual aid society he forces everyone he knows to subscribe to, including, after a night of drinking, Konno. Then, Fukushima, and Hiasa seems to have been in one of the devastated areas.

Konno goes hunting for his lost friendship that never was. But then, it was a very special friendship. We have seen that. Only Hiasa has this other side. And he has warned his friend, with another haunting speech about the deeper shadow behind a face, the warning that he's not all he appears to be. This, Konno finds out something about, as revealed in scenes of meetings first with Norihiro's father (Jun Kunimura), then with his older brother, Kaoru (Ken Yasuda).

This film is a little too slow and too long, but early on it reminded me of Lee Chang-dong's wonderful, haunting Burning (NYFF 2018) created by just spicing up a bit a Haruki Murakami short story. One feels one is very much in the realm of the short story here also. Director Ohtomo Keishi has worked here from a novel by Shinsuke Numata, which won the Akutagawa prize in 2017. It's the essence of this story, and of the film, that the secret of Hiasa, Konno's intense, mysterious friendship, slips away like the fish Konno releases at the end of the film. But that seemed somehow rather anticlimactic.

This is a movie whose beginning and middle are better than its end. James Hadfield is cruel but not inaccurate in his Japan Times review when he concludes that the film finishes "in an awkward hinterland," not "atmospheric enough" to be a "mood piece" nor "taut" enough to "satisfy as a suspense story." Ohtomo doesn't hit a home run in his foray into art filmmaking. Nonetheless this is a memorable, in some ways classic, theme.

Beneath the Shadow 影裏 , 135 mins., debuted Dec. 2019 at Hainan, and was released in Japan Feb. 14, 2020 (Sony Music Entertainment). The dp was Akiko Ashizawa. Screened for this review as part of the Aug. 28-Sept 12, 2020 virtual cinema New York Asian Film Festival.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-20-2020 at 12:20 PM.

-

A BELOVED WIFE 喜劇 愛妻物語 (Shin Adachi 2019 )

SHIN ADACHI: A BELOVED WIFE 喜劇 愛妻物語 (2019)

AZAMI MIZUKAWA AND GAKU HAMADA IN A BELOVED WIFE

Hellish family road trip seen as redeeming comedy

Shin Adachi is not a conventional Japanese filmmaker or one who fits time-honored cultural norms of understatement and politeness. As a screenwriter he debuted in 100 Yen Love (Japan's 2015 Oscar submission) with the story of a thirty-something woman who became a boxer to help a guy who is a jerk. In his directorial debut 14 That Night he focused on a high school student whose ambition is to fondle the breasts of a porn star. This time, adapting his own novel, he depicts a highly unappealing version of himself as Gota (Gaku Hamada), a currently unsuccessful and sometimes lazy screenwriter whose big complaint is that he is not having "sex" (the Japanese use the same word) with his wife. The film focuses on a hellish and unenjoyable but also funny road trip the short, dumpy Gota drags his wife and TV-addicted daughter on to Kagawa Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku gathering information for a screenwriting assignment, a film about a high school girl who makes udon commissioned from Gota's agent as a vehicle for a financier’s mistress.

Chika (Azami Mizukawa), the shrewish wife, never hesitates to berate Gota. And she seems justified. He hasn't been much of a provider. He says what he's earned in the last year amounts to 500,000 Yen, which is less than $5,000. Now, he keeps bugging her to have sex with him, meanwhile indulging in porn through a virtual reality headset and getting stopped by police for looking up the dress of woman passed out drunk on the street. Perhaps it's no wonder Chika goes to comical (or wearying) efforts to save money. Not a pretty portrait either, Chika dresses like a slob and drinks to excess. She's also however currently the family breadwinner. The family dynamic is ultimately leavened by the presence of sweet young daughter Aki (Chise Niitsu), one positive fruit of this unglamorous ten-year marriage.

It all seems dull and sordid, but Adachi pointed out in an interview with James Hadfield of The Japan Times that Gaku Hamada was chosen because his diminutive, baby-faced look makes him ultimately hard for audiences to dislike. Adachi told Hadfield it's all based on his "actual experiences" but that the movie makes it (the behavior) "all look better." (Hadfield's aside is that he presumes the cramped, messy apartment used for the family here must surely be "rather less fancy" than Adachi's own current one.) It emerges that Adachi is a child of the eighties and kitchen sink TV series like Taichi Yamada's which Adachi saw as "unsparing" and "harsh" but also "big-hearted." A sweet-and-sour mixture is what Adachi strives for here, though with this autobiographical protagonist who's without shame or politeness in front of his wife and daughter and has drag-out fights with his wife, it can wind up being hard to find the big-heartedness or sympathy.

Adachi is a cutting-edge, increasingly in-demand Japanese writer and director who is seeking to take local cinema in fresh directions that make Peter DeBruge of Variety compare him to Alexander Payne and Noah Baumbach or, even more, Woody Allen. Deborah Young in her Hollywood Reporter review of this high-profile new film notes its "weird originality" and, underneath its "near-constant vulgarity," "a beating heart." Maybe so, but a lot of this seemed tiresome and icky to me. Woody Allen never had this kind of crude, kitchen-sink quality and at his best is much funnier than this as well. Note: the current subtitles are below par in quality.

A Beloved Wife 喜劇 愛妻物語, 117 mins., debuted at Tokyo in competition Nov. 2019. Screened for this review as part of the New York Asian Film Festival, presented virtually Aug. 28-Sept. 12, 2020.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-20-2020 at 12:21 PM.

-

THEY SAY NOTHING STAYS THE SAME ある船頭の話 (Odagiri Joe 2019)

ODAGIRI JOE: THEY SAY NOTHING STAYS THE SAME ある船頭の話 (2019)

Of time and the river

This ambitious and beautiful Japanese historical film was directed by Joe Odagiri with cinematography by Wong Kar-wai's superb muse Chris Doyle and lovely but a bit obtrusive music by Armenian jazz pianist Tigran Hamasyan. The forty-four-year-old Odagiri's Japanese Wikipedia page is immense. As Deborah Young tells us in her Hollywood Reporter review, at home Odagiri's known as a "gothic rebel with a reliably huge female fan base," and he has been involved in many films and TV series. He wants to do something art house and impressive here, and he does, if it might have used some tightening up here and there. He may be inspired in his calm setting and aging, simple protagonist by Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring by Kim Ki-duk whom he worked with on the latter's Dream, but Akira Emori's old boatman Toichi doesn't spout Zen wisdom like Kim's old dude. He's just a stoical, unlettered old man who's modest and a bit lost but an integral part of a beautiful, natural place.

Toichi is always ready to row village-to-town passengers of all sorts, loud or quiet, offensive or polite, across the wide mountain valley river in his flatboat whenever asked. He says it takes three days to learn the oars, three years to learn the pole. It's all he knows how to do, and he does it tirelessly and lives in a shack at the bend in the river. His frequent companion is a loud, goofy young man called Genzo (Nijirô Murakami, a media cutie in Japan, here doing a nice character turn), who provides such delicacies as bean paste baked on summer rocks.

But remember Marvell's "To His Coy Mistreess, "at my back I always hear/Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near"? At Toichi's back, in the distance, rarely seen, he always hears the sounds of a bridge building over the river. Genzo hates the idea of faster, busier people, loss of the few coins for his crossings for Toichi, of his livelihood. They dream, once vividly, in black and white, and violently, of attacking the bridge and its builders and stopping the whole thing. This never happens. At the end, the bridge is built (it's surprisingly pretty, a soft red), the town and village people rush back and forth, and Toichi is a back number, advised to take it easy and not think too much by the doctor.

The Japanese are great at historical, costume cinema, and this film set in the Meiji era (late 19th to 1912) shot by the master Christopher Doyle sets an enchanting mood. This is also a nation of storytellers. Americans saw this combination epitomized early in a US import triumph from Janus Films, Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon, which skillfully blends three Ryunosuke Akutagawa stories within a haunting mood. This is not that. So often I longed for the brilliant storytelling this movie hints at, feeling it has the material, and just needs to rearrange it a bit and cut out the fat - or "kill his darlings," since surely there are numerous beautiful passages Joe was loathe to part with.

Nijirô Murakami says somewhere a Jim Jarmusch film is his favorite movie, and one of the other key players, who plays Nihei (Masatoshi Nagase) was in Jarmusch's Mystery Train, so it may make sense that I thought of Dead Man, the way its incidents flow from one scene to the next and with death, like here, hanging around the corner. They Say Nothing Stays the Same has very good scenes in this glamorous package, but they don't quite mesh enough, and there's too much space between them. Scenes are vivid and good nonetheless.

The first big one, disturbing the generally tranquil life, comes when Toichi's flatboat runs into a lump of something floating in the water. It's a dead girl. Only when he lugs her to his shack, Genzo discovers she's not dead, she's breathing. She may be called "Fu," which Toichi thinks it would be nice if it meant "wind," but IMDb knows her only as "Girl" (Ririka Kawashima). Toichi treats her wounds with Genzo's mix of mudwort and bear bile, but they fear she was hit on the head, and when she finally speaks she has forgotten all about her life. On the river Toichi hears all rumors and there is one of a family massacred at Ichinomiya with one girl carried off. They think Fu may be the girl. Her muteness seems to confirm this. Later she begins to speak, then runs off, later comes back and lives with Toichi and eventually becomes his helper. She is dark and knowing. Once, she jumps off the boat into the water. Toichi divers after her, to rescue her, but in a typically lovely underwater scene, we find she swims like a fish. They live, by the way, off fish-on-a-stick sandwiches. Later the story about a massacre at Ichinomiya turns out to be just a story.

We meet, with Toichi, rude, impatient people who treat him abominably, including some bridge engineers, and some nasty little boys who throw stones and mock, all giving a sense of evil in the world. But ultimately the message is ecological. Since the bridge is building, the water is dirtier, and without clear water there are no fireflies. "Fu" (Girl) says fireflies are more important than bridges. We meet also, with Toichi, a girl ghost, in ragged grey clothing - another thing the Japanese excel at is ghosts - and she says she is watching him. Maybe she's going to take him away, with the tides, with the seasons.

It all ends, in a way, with winter, which brings astonishing scenes of snow that show the region where this film takes place is more beautiful, grand, stark, and mountainous than it seemed in the closer, lusher greenness of summer.

Before the snow there is a great storm with heavy rain when the straw period raincoats come out. The Girl and Toichi sit huddled in his shack when Nihei, a longtime passenger and friend, arrives carrying the body of his dead father, asking the favor of Toichi to aid him in fulfilling a promise. His father spent his life hunting animals; Toichi ferried him to his hunting grounds and considered him "a great man." His last wish was to have his body offered to the animals he hunted to repay those lives he took. But this must be done in secret. So they, with the girl, take the corpse of Nihei's father into a dark and rain-drenched forest across the river. (Here in particular the score of Tigran Hamasyan seems a little too sweet and prominent.)

A Letterboxd contributor comments that the film is "really good for 95%" of the way but in the other 5% chooses to "drive off a cliff" - breaking the calm and peace too much. James Hadfield is similar in The Japan Timeswhen he says Odagiri "can’t quite reconcile the film’s mood-piece feel with his more dramatic urges." This is indeed a challenge in such a long film (two hours and seventeen minutes): ruthless editing might have helped. But, again as Hadfield says, Odagiri is probably too in love with his beautiful cinematography and high quality cast. So was I.

They Say Nothing Stays the Same ある船頭の話, 137 mins., debuted at Venice (in the Giornate degli Autori section), where Odagiri was also present as one of the stars of Lou Ye’s (not as good) competition spy film Saturday Fiction Sept. 2019, also showing at Busan, Montreal, Hong Kong, and Taipei. Screened for this review as part of the virtual 2020 New York Asian Film Festival (Aug. 28-Sept. 12).

RIRIKA KAWASHIMA, AKIRA EMOTO

CINEMATOGRAPHER CHRISTOPHER DOYLE

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-28-2020 at 10:08 PM.

-

ONE NIGHT ひとよ (Shiraishi Kazuya 2019)

SHIRAISHI KAZUYUA: ONE NIGHTひとよ(2019)

TAKERU SATOH, RYOHEI SUZUKI, YUKO TANAKA AND MAYU MATSUOKA IN ONE NIGHT

Family dynamic not improved by spousal murder

Ths screenplay of One Night was written by Shiraishi’s collaborator Takahashi Izumi and based on a 2011 play by Kuwabara Yuko. Shiraishi's a bit of a NYAFF bad boy (we know him from The Blood of Wolves and Dare to Stop Us), and here returns with a multilayered meditation on the stigma of violence. This time he focuses on a family.

The film opens with a flashback to a stormy night when Koharu (Yuko Tanaka) returns home, in mannish taxi driver garb, to inform the three children that to eliminate the family's pain and suffering she has murdered their violent, abusive father by running over him with her taxi. She will turn herself in now, and will go to jail, but they are free. She promises to come back in a decade - no, make that fifteen years - to rejoin them. Meanwhile they will be safe and can pursue their lives unimpeded.

Well, Koharu has made a brave sacrifice, but of course she's left her two sons and daughter to grow up without a mother and father and in the shadow of yet another trauma. It turns out that in the absence of the parents their mother's family runs the provincial taxi company and takes care of the kids. But in the wake of the ugly physical abuse of the murdered father (of which we get a hideous glimpse) and the outsider status bestowed upon them by having a murderer for a mother, the three kids aren't exactly what you'd call lucky, or the town's favorite young people.

We quickly jump forward fifteen years, when Kooharu appears, looking totally gray and surprisingly neat and respectable. It seems she has spent several years since her release working at different jobs elsewhere but they haven't been in touch. She hesitated to come back, she says, but she has kept her promise. She had reason to hesitate.

Now we meet the three offspring as they are now. Yuji (Takeru Satoh), the talented, smart one, has a dashing, saturnine appearance and a chip on his shoulder and is cultivating literary fantasies while actually working for a porn mag in Tokyo - where a scene shows his lowly status. He's come back back home to the provinces now for the first time in a while to meet mom, but he's the least happy with her return, or with anything. He's meanwhile gathering data on the family scandals and horrors for a planned novel, taking constant snapshots of the family scene with his smartphone as part of the preparation. As for the tall, still stuttering Daiki (Ryohei Suzuki), he is in a foundering marriage to a wife whose family business he's been working at, though the wife wants to divorce him and leave, taking their little girl with them. A brief scene fills us in on that.

Most positive - she insists their mother did save them from a much worse life - is the daughter, Sonoko (Mayu Matsuoka),a pretty young woman who dreamed of being a hairdresser, and was a hostess at a snack bar, but lately, as she tells Yuji, focuses on being a call girl, an "escort," if you like, while getting drunk every night at a karaoke bar.

Koharu's brother's family, who've been running the taxi company successfully, seem more happy to see her. We meet some of them. Yumi (Mariko Tsutsui) is having an affair while caring for her senile mother-in-law. Michio/Doushita (Kuranosuke Sasaki) is a new driver. He arrives around the same time that Koharu does, looking a bit the worse for wear but mercurial and all smiles. He doesn't drink, do drugs, or gamble, which got him hired right away. But following scenes where he's reunited with his teenage son after a long separation and encounters an unwelcome former colleague, it emerges that he has a problematic past of his own that he's trying to escape from.

Whatever the family or taxi firm employees may think or however well they get along with Koharu, the locals of this provincial town quickly grow hostile to Koraru's return when they hear of it: her presence, seen from a slight distance but still too close for them, is a scandal. Local news has reported on it and little flyers multiply around the taxi company broadcasting that there's a murderess, a husband-killer, in town. The siblings hasten to clean up the company vehicles that they awaken to find covered in abusive white graffiti. If this film is good at anything, it's mess: cluttered, disorganized rooms, littered spaces, graffiti-covered walls and vehicles are, perversely, a delight to the eye. Sometimes the Japanese seem to be reacting to the design austerity of their traditional culture, the empty tatami-spread rooms, the rolled-away futons. Of the graffiti-decorated cars, Yuji takes snapshots with his phone, but promises his saying it's to show Koharu is only a joke.

Koharu's return is a classic gesture for a play. It causes all the old traumas to come back to mind. Realized cinematically it also brings about a lot of things - like the abusive fliers and graffiti. Perhaps the cathartic reconciliation wold work better on the stage. But what Shiraishi can provide that a playwright can't is another big storm outside.

James Hadfield of The Japan Times, who calls this "the most conventional thing [Shiraishi has] done to date," sees this a treatment of themes Kazuya cares about: "whether the ends ever justify the means, and if there’s any hope for people who commit awful deeds. He thinks that some of the early scenes show "taut execution" but finds the climax to be "a disappointing mess." An Italian critic (the film debuted at Udine) calls it "hasty" and says that's the "only fault." Well, the finale is busy. Some of the physical clutter that provides the film with its pleasingly icky contemporary texture may seem to pour over into overelaborate action. But nonetheless those final minutes are cathartic. There's nothing like family for drama.

One NIght ひとよ (Shiraishi Kazuya 2019), 123 mins., debuted Oct. 2019 at Tokyo, showing Nov. 2019 at Taipei, and included in the online Jun.-Jul.2020 Udine Festival. It was screened for this review as part of the virtual 2020 New York Asian Film Festival (Aug. 28-Sept. 12, 2020).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-29-2020 at 10:41 PM.

-

MIYAMOTO 宮本から君へ (Mariko Tetsuya 2019)

MARIKO TETSUYA: MIYAMOTO 宮本から君へ (2019)

SOSUKE IKEMATSU, LEFT, IN MIYAMOTO

Enthusiastic salaryman

Early this year the Harvard Library's film collection featured a series on Mariko Tetsuya called "Self Destruction Cinema" and that may be the best place to begin in describing the latest of his two more high-profile films (he has been active as a writer and maker of movies and TV mini-series since 2003). The previous film is called Destruction Babies (and that's the title, transliterated in Japanese characters, Disutorakushon beibîzu) and features someone more sadistic and more masochistic than young Hiroshi Miyamoto. (The full title this time is From Miyamoto to You and there was a miniseries, with the same actors and director, based on the manga series "Miyamoto kara Kimi e" by Hideki Arai.) Sôsuke Ikematsu plays the role in both and he owns the role; there are several other actors from the miniseries also here. Ikematsu is awesome as the baby-faced young salaryman who goes for broke in feelings and commitment, no reserves, no good sense, no physical fear.

Cinema of extremes, also. Miyamoto is some kind of madcap hero, but no role model. He takes it on himself to rid a pretty young woman, Yasuko (Yû Aoi) of an unwanted ex-boyfriend. Then she takes to him and they have sex and get involved. Next thing you know, he's meeting her parents, the Nakano family, who own a company. The mother loves that he drinks like a fish. (In some parts of Japanese society it's considered a good social trait to be able to drink a lot.) There is a sequence of extreme beer drinking. Miyamoto drinks so much he later passes out in a comatose sleep while with Yasuko. A member of the Nakano family is a ruby player and has giant bruiser-type rugby player friends. One of them comes and rapes Yasuko, right in front of Miyamoto, stretched out sleeping like a baby. He's so out Yasuko's screams never wake him. The rape is the hardest of a series of violent, hard-to-watch sequences in this movie of gonzo interpersonal violence and scream-fests that sometimes seem grating and at others, purgative.

When Miyamoto finds out what has happened to his girlfriend (he has to guess, which makes the sequence more painful), he becomes determined to take revenge against the giant rugby player rapist. He is also more than ever determined to marry Yasuko. Only what has happened has made Yasuko unable not to loathe him. She called on him for help again and again and he did not budge. Her revulsion will change, somewhat inexplicably. The storytelling provides no clear logical explanation of Yasuko's change of feelings toward Miyamoto.

In many scenes Miyamoto is missing three front teeth, because in his first of several violent encounters with the rapist, he gets a giant fist in the mouth ("like a bowling ball," he recounts afterward) and loses them Later he gets more damaged, but in a final encounter between the two high up on an apartment building balcony, Miyamoto manages to reverse roles by doing damage where it hurts most and capitalizing on the advantage inflicting excruciating pain gives him over his huge adversary.

The dialogue is at two levels in this movie, low and high, with nothing in between. People are either talking calmly, under their breath (with some voice-over narration) or, when it gets intense, shouting at the top of their voices, possibly spouting blood or foaming at the mouth as they do so. Particularly memorable in this vein is a scene where Miyamoto comes to propose marriage at the top of his lungs to Yasuko in the middle of her place of work. There is scattered applause, but Yasuko screams back in front of everybody her absolute refusal and desire never to set eyes on Miyamoto again.

Everyone (in the English language comments I've found) talks about how cringe-inducing and hard to watch a lof ot the action is in this movie. Japanese fans of the mang seem to have been delighted by the film. "You are in a comic book world," one says, and that sums it up. The Japanese are not as offended by or judgmental about fictional violence or extremes as Americans are. Even if you're shocked, this is also compulsive watching, except for the rape, when I wanted to look away. This is not a Cinema of Cruelty a la Antonin Artaud or spatter action a la Grand Guignol. Many blockbuster action of thriller films have more violence, cruelty, and blood. Here, it's mitigated by Miyamoto's good-heartedness and sincerity. His courage is foolhardy, but his determination and loyalty are worthy of the tales of courtly love. In its warped, hysterical way, Miyamoto is a rom-com. Wait for the Judd Apatow-produced Hollywood remake.

Miyamoto 宮本から君へ, 129 mins., opened in Japan Sept. 2019 and Hong Kong Nov., 2019; featured at Chicago Oct. 2019. Screened for this review as part of the virtual 2020 New York Asian Film Festival.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 08-29-2020 at 02:26 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks