-

BERLIN & BEYOND Mar. 2022

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-08-2022 at 07:42 PM.

-

NEXT DOOR/NEBENON (Daniel Brühl 2021)

DANIEL BRÜHL: NEXT DOOR/NEBENON (2022)

PETER KURTH AND DANIEL BRÜHL IN NEXT DOOR

TRAILER

Daniel Brühl enjoys seeing his ego deflated, but the critics aren't very impressed

In Daniel Brühl's directorial debut, he plays as an ironic version of himself. To believe the opinions of several different Anglophone reviewers, the result is both a vanity project and a film without vanity. Is that possible? In a way, yes, as a man can be vain of his own modesty. Playing this "Daniel" who appears in every frame of Next Door Brühl allows himself to get severely pummeled, and his privilege is held up to question. Those critics also think this rather a slight film. Though some of the details are a bit over the top, I found it gripping all the way through. Its giddy sequence of revelations reminded me, for some reason, of Fred Schepisi's 1993 Six Degrees of Separation, written by the excellent John Guare, with the young Will Smith distinguishing himself as a junior con man eager to - distinguish himself. This isn't as good a movie as that, but it has some of the same excitement of breathlessly revealed information. This is a nail-bitingly entertaining film and a good one for the Opening Night film of San Francisco's 2022 Berlin and Beyond festival, which is how I saw it.

Though the writing is all by Daniel Kehlmann, this screen "Daniel" is Brühl's conception and so, then, is the mockery of guys like him: a highly successful German-Spanish movie actor living in the Boho Prenzlauer Berg district of Berlin. The opening sequence shows off that he has all the perks: glamorous top floor apartment with its own private elevator, Spanish maid to take care of the kids, stylish, accomplished wife, Clara (Aenne Schwarz), a doctor, comfort, glamor, fame, ambition. As the straight-through real time-ish action begins, it's early morning and he's off to London to try out for a role in a superhero blockbuster of the "Darkman" type.

The real Brühl, who grew up fluent in four or five languages, has indeed had roles in such films, with more coming. There is a certain preening self-satisfaction - or is he just excited and happy? - in the way "Daniel" does a light workout, showers, freshens up, dresses, congratulates the maid in perfect Spanish, fatuously ("How could we live without you?" - she is not expected to reply, though "Not easily, I hope," would be a good one), says a quiet goodbye to Clara, still in bed, and, excited, fresh-faced, wet-haired, rolls off with his small wheeled suitcase full of nervous anticipation of the tryout in London.

A blurb says the film explores "gentrification and social inequality in Berlin": nonsense. This is a process film, and that process is the destruction of Daniel's ego. He realizes it's much too early to take a taxi to the airport, and so dismisses the one that's been called, and heads instead to a local dive bar to kill some time. It's name is Zur Brust, and he likes it because its bad coffee reminds him of his mother. Our attention is repeatedly called to the fact that the proprietress (like most other people) knows him - but, though he frequents the place, he has yet to learn her name. (It's Hilde, and she's played by Rike Eckermann.) Daniel is periodically asked for a selfie or an autography, which he always gives, and he is deflated, to our amusement, when he falsely assumes one couple wants to be photographed on either side of him when they don't know who he is and are only asking him to take their picture.

A big man is staring at him from the bar. He looks like Robert Mitchem gone very much to seed - which is saying a lot, considering how rumpled the late Mitchem became. His name is Bruno (Peter Kurth) and he is going to be Daniel's nemesis, the dismantler of his selfhood. Many beers and many schnapps later, Daniel will have missed his flight to London and misplaced his reputation.

No need to go into details, because the devil and the fun is in them. Suffice it to say Bruno has for quite some time, in some ways somewhat implausibly, been spying on Daniel, "stalking" him, Daniel later says, for quite some time, and what he gradually comes out with is devastating. But before that, and this is the good part, Bruno sententiously unveils a series of derogatory, quite irrelevant opinions of Daniel's acting in general and some of his main films in particular that are versions of films Brühl has appeared in. These include what Bruno calls "the Stasi film," which refers to the 2003 Goodbye Lenin, the motion picture directed by Wolfgang Becker in which Brühl first became internationally noticed. Bruno lived in East Berlin back in the day and he's one of those who thinks it was not so bad. The Stasi weren't monsters, as shown in the movie, according to Bruno, but regular guys. We will not be surprised later to learn some ideas Bruno doesn't like, he refers to as "Fake news." So like the Lives of Others cast, Bruno, maybe was Stasi himself?

Bruno is an elaborate construct, nicely made manifest by Peter Kurth. This is a two-hander in which Kurth has the key role, though he'd have nothing to do without Brühl, who does all the reaction shots, from feigned disinterest, to contempt, to annoyance, to rage, to floods of tears. Yes, he gets to show off.

Next Door may not quite know how to end itself. Clara appears, having received damning information at her offices. She appears to present a united front with Daniel, but then, does she? Guy Lodge comments in his Variety review on the "An oblique, eerie finale," showing Vicky Krieps now occupying Daniel's home, that's "suddenly more intriguing than anything else in the film." Yes, there are more complex sort of film. But this one, like Six Degrees of Separation, plays its one note with gripping intensity to the end. But the identity thriller entertainment function trumps others; the probing of ego and privilege could have gone much deeper. Though I like this more than the Meta-critics do, I can't give it more than a C+ and hope the real Daniel does better next time behind the camera. (I do not know German, and so can't tell if the local reviews have been better.)

Next Door/Nebenon, 92 mins., debuted at the Berlinale Jun. 11, 2021; it appeared at 8 or 20 other festivals including Taormina, Stockholm and Taipei. Screened for this review as part of the San Francisco Mar. 2022 Berlin and Beyond festival where it shows at three venues:

Castro Theatre

March 11, 2022

6:30 pm

Landmark's Aquarius Theatre

March 14, 2022

6:30 pm

Landmark's Shattuck Cinemas

March 15, 2022

6:00 pm

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-04-2022 at 12:19 AM.

-

TACHELES - THE HEART OF THE MATTER/ENDLICH TACHELES (Matthes, Schramm 2020)

JANA MATTHES, ANDREA SCHRAMM: TACHELES - THE HEART OF THE MATTER/ENDLICH TACHELES (2020)

YAAL IN ENDLICH TACHELES

A Jewish-German 20-something tries to cope with the Shoah through designing a video game. It doesn't work.

Yaal, the main figure of this film, was hard for me to like, and I still don't like him, but you gradually sympathize with his plight. Yaal has chin whiskers and a bushy mop of hair tied in the back. He grins like a doofus and is chubby, but energetic. Born in Israel but raised in Germany and now a Jewish Beliner, at the age of 21 he decides to cope with his Jewishness by co-designing a video game about the Holocaust, in which the main co-designer is a non-Jewish German friend, Marcel, who has discovered he is directly descended from an SS Officer. They lean toward building in positive options: the little Jewish kid gets to survive, saved by the benevolence of a good-hearted SS officer who, you know, is just doing a job and doesn't really hate Jews and all that. Though his great uncle Roman (originally Romak) died at the hands of the Gestapo as a small boy and his paternal grandmother Rina has lived her life with survivor guilt, and his father has lived his traumatized by this, Yaal has been allowed to grow up without Jewish religion or even ethnicity, a Jew who wouldn't know he was Jewish except that sometimes in school anti-Semitic remarks were still thrown his way. Oh yes and then he happens to be fluent in modern Hebrew as well as German and was born in Israel and has a grandmother there: that might make him Jewish, mightn't it? Eighty years of wailing, isn't that enough? Well, actually not. Yaal will learn - or appear to learn; the authenticity of the action is not always convincing - that at two generations removed, he still has to cope with the Holocaust as not only an historical legacy but an intimately personal, familial one, and that his approach was wrong. But as the film ends, he has not found the right one.

Yaal hardly knows he's Jewish, but he knows. He yearns to thrown off the yoke of Jewish gloom, the suffering, the cloak of tragedy he sees always thrown over Jewishness. Can't Jews have fun? Isn't it about time to He may not be aware of Jewish humor. He seems not much aware of anything. This film will show Yaal come to some kind of realization. When he sees and learns about the ruins of the Krakow ghetto, he cries. Finally he decides the video game isn't going to work - at least in this form.

The first trouble is the cluelessness of the protagonist, who seems lacking in depth or even good sense. The second is the approach of the filmmakers. They are shooting intimate events that might have played out differently without a camera present. This is signaled right at the start with an up-close shot of Yaal naked in the shower - an ironic place indeed to begin a Holocaust film - bopping and jiving and grinning for the camera and calling attention to the dp and sound recordist's presence with him.

Yaal, Marcel, and the artist, Sarah, go to Krakow and camp out, apparently in a large empty mansion there, which they use as a studio for their brainstorming for the video game that Yaal tentatively calls "Shoah. While God was asleep" (Als Gott schlief). They acquire WWII paraphernalia in a street market where Yaal bargains. Marcel giggles at his prowess and the possibility that this is an innate ethnic skill is thrown out. More tellingly, the two boys enjoy trying on jack boots and clicking their heels, as in an old movie about Nazis. When Marcel insists the game SS officer "isn't even a Nazi," the filmmakers butt in from behind the camera to object.

Later Yaal's father arrives for a visit. He is shocked to see these kids designing a game in which Jews can defend themselves and Nazis can act humanely. As various commentators have said, including Mira Fox of the Jewish paper The Forward,, this process verges on "victim-blaming or even Holocaust denial." Her article's title is "What if we could resolve generational trauma through…a Holocaust video game?" Obviously we can't. When Yaal meets at some opoint with his mother, sh also tells him he can't get away with a Holocaust video game with positive outcomes. Or he can: but how is that going to help younger generations understand the Holocaust or help Yaal to cope with his heritage?

In Krakow Yaal and his father visit the ghetto site and have a ceremony about the grandmother's slaughtered little brother and his father weeps copiously there and also later when they meet in a cathedral with the representative of a Polish family that at one point helped protect Rina and her little brother, but then, could not. It seems to emerge that Rina was more present than she had ever said when her brother was taken away, and that all her life she has suffered from terrible guilt. This is part of Yaal's learning process, but also, importantly, therapy for his father, who pours out the wail about how growing up in Israel his parents were so under the "black curtain" of the Holocaust they could not even celebrate his and his siblings' birthdays. These events, these new awarenesses, seem to bring more understanding and closeness between father and son.

My need to dismiss this whole business as shallow and ridiculous is tempered by the awareness that these are moving confrontations of real events that illustrate that into the third and forth generations the Holocaust and WWII are still very present. But an uneasiness remains because of the film's manipulative, intrusive process, which is inherently flawed and in so many ways uninformative, even arguably deceptive. From other sources we learn that Yaal was originally working for the filmmakers, who were planning a film about how younger generations deal with a Holocaust background, and then when they learned about Yaal's personal story they decided focusing on him in particular would be more interesting. But how much did they engineer things every steep of the way? [IEndlich Tacheles,[/I] this film's title, uses a Yiddish word adopted into German meaning "straight talking" to mean something like "finally, the truth." This film is pointing to an attempt to come to the truth that's fogged not only by trauma but by filmmaking methods that are inherently, subtly, deceptive.

Outside the film - but it ought not be - it develops as Fox's Forward article tells us based on an interview with Yaal, that he is still working on a Shoah computer game, one in which you can choose multiple different narratives, "but all of the choices lead to the same result, the death and horror of the Holocaust," teaching players the lesson that while people thought they had choices, they did not. The false start has led him to that wisdom.

Tacheles - the Heart of the Matter/Endlich Tacheles, 105 mins., debuted in May 2020 at Munich International Documentary Festival where it was one of 12 films nominated for the German Documentary Film Award, and at the 2021 New York US Human Rights Watch Film Festival. Screened for this review as part of this year's San Francisco Berlin and Beyond Festival, Mar. 11-16, 2022.

DATES & TIMES

Castro Theatre

March 13, 2022

2:30 pm

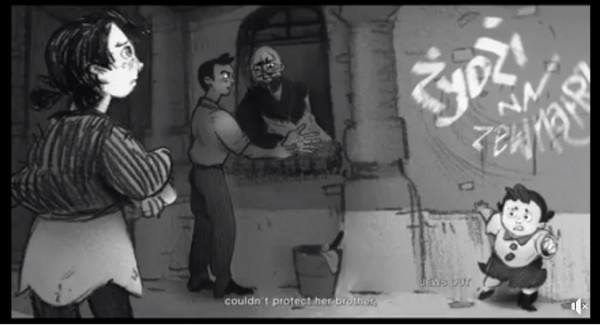

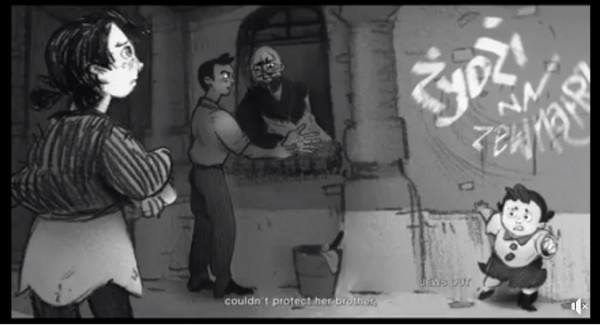

A SKETCH FOR THE GAME IN ENDLICH TACHELES

German: kino-zeit.de [Bianka Piringer] (German)

Article in DW Made for Minds about the film.Als Gott schlie

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-07-2022 at 03:25 PM.

-

DEAR THOMAS/LIEBER THOMAS (Andreas Kleinert 2021)

ANDREAS KLEINERT: DEAR THOMAS/LIEBER THOMAS (2021)

ALBRECHT SCHUCH IN LIEBER THOMAS

Tumultuous biopic of an East Berlin writer who rose in the Cold War may be for his admirers only

The "Thomas" here is a real person, Thomas Brasch (popular German actor Albrecht Schuch), a Jewish British-born East Berlin poet and director (1945-2001). His work and personality, as shown here, were too much for the Soviet era German communists, though he never fully renounced his loyalty to the GDR. This despite its having imprisoned him - apparently at the behest of his own father (Jörg Schüttauf), a party official - for pamphleteering in 1968 to protest the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In rich black and white, Dear Thomas, whose title announces it will be a love letter, is a narrative effusion of a biopic that regularly introduces Brasch's dreams without warning and revels in his relentless bad-boy behavior.

To judge by the German Wikipedia entry for him (the English one is woefully scanty), many significant details of the man's life, and especially his literary career, are missing in this movie, which doesn't try for completeness. Given the impressionistic, spotty storytelling, how many facts are left out, the 150-minute run-time seems excessive, though the action is continually enlivened by Schuch's committed and spirited portrayal of the lead. The early segments are wearying. If you stick with it things pick up in the latter part, especially when Brasch finally moves for a while to the West and spends an interesting, creatively rewarding period in New York City.

It's been commented that the many women around Thomas are, in the film, not much more than decorative furnishings, despite being played by well-known actresses. When his father denounces him to the Stasi, his girlfriend is Sanda (Ioana Jacob). When he gets permission to leave for the West, it's Katarina (Jella Haase). There's the sequence of a young woman who comes to Thomas for help after she's been jailed after denouncing her father for abusing her sister, made memorable by the shocking dream he has which, like the others, is woven in so seamlessly the unalert, uninformed viewer might think it's real. Director Andreas Kleinert seems to revel in these dreams and they are the fun parts while the strictly biopic scenes sometimes feel more dutiful.

Sometimes on the other hand the staging of real events is somewhat unconvincing, such as the imprisonment, which seems like a not-so-bad dream anyway: Thomas is sentenced to two years and some months but released after barely more than two months. His father, who has plenty of political clout, apparently has had second thoughts and gets his son out of jail before it has seemed real to us. On parole he is assigned to work - all good material for his writing, everyone thinks - "as a milling cutter at the Berlin transformer factory 'K. Liebknecht'" (German Wikipedia). For the messy-looking mill scenes it looks like all the actors have rubbed dirt on their faces to make it look authentic, which has the opposite effect.

After a while Thomas goes through a cocaine period, snorting up masses of white powder and sometimes looking quite gaga. Even his cigarette smoking is used to convey a sense of the man's wild, macho self-destructiveness. When he lights his best friend's cigarette by their putting the two ends together and puffing, it's almost sexual. Schuch often jumps up on things, chairs, tables, to show Thomas' impulsiveness, his rather threatening enthusiasm. And yet though he's seen tapping away energetically on a series of manual typewriters, and admirers gather round to hear him read, we're always hearing of non-publication or play cancellations. And so when in the West he seems an instant celebrity ("he is acclaimed and his books become bestsellers," in the film blurb) it's hard to see how that happens because the film has had a hard time showing how he's become known.

Thomas is devastated when his artistically promising younger brother Klaus (Joel Basman) dies (at 30, of a pill-and-alcohol cocktail, though the film omits the details), but in the elision of scenarios his wife brings him a letter showing his first film has gotten funding just when he's gotten the news of Klaus' death and is standing on the roof thinking of jumping off. Next thing we know his metaphorical crime drama Angels in Iron is being shown at Cannes and his father, never out of the picture, is there telling him it's "very impressive" but says "Where is your novel? Did you skip it?" The breathtaking fluidity of these sequences is admirable.

As an example of Thomas Brasch's way with words the film - which early on tellingly shows him writing his prose-poetry, neatly, all over a woman's naked body - cites the following lines, which are used as chapter headings along the way:

"What I have I don't want to lose, but

where I am, I don't want to stay, but

I don't want to leave the ones I love, but

the ones I know I don't want to see any more but

where I live I don't want to die, but

where I die I don't want to go:

I want to stay where I have never been."

These paradoxes may sound facile, at least in English, but they make nice headings for the film's seven chapters. For the last chapter, when Brasch is 56, the age at which he dies, he is played by an older actor, Peter Kremer. (As an 11-year-old sent to military school, he's played by Claudio Magno.) For the final moments, the wracked-with-coughs but still vigorous and smiling Thomas steps permanently into a dream. This whole final passage is nicely done,, flowing into the credits with baroque music and the sound of trumpets. This is a movie that seems to have found itself only when it's about to end.

Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck's even longer study of a German artist who went westward and became famous, Never Look Away/Ohne Titel, tells a story that riffs more freely off its biographical basis and in a more focused ad more emotionally engaging way. Though his admirers may love it, and it has numerous moments of tumultuous fun, I did not enjoy Dear Thomas as much and can't really recommend it.

Dear Thomas/Lieber Thomas, 15o mins., debuted as an Official Selection at Munich July 2, 2021 and won Best Film plus an acting award for Albrecht Shuch at Tallinn Black Nights Nov. 23. Screened for this review as part of San Francisco's Mar. 11-16, 2022 Berlin and Beyond festival.

DATES & TIMES

Castro Theatre

March 12, 2022

6:00 pm

Landmark's Shattuck Cinemas

March 15, 2022

8:15 pm

David Katz published a review of this film in cineuropa that's clear-eyed both about the film ("it’s impressive work in itself making Jean Seberg and Jules and Jim references seem quite this uncool") and its subject ("there’s a poignancy in his flailing attempts to actually resemble the great littérateur he clearly fancies himself as").

Another rare English-language review is by Amber Wilkinson for Eye for Film.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-07-2022 at 08:20 PM.

-

MR. BACHMANN AND HIS CLASS (Maria Speth 2021)

MARIA SPETH: MR. BACHMANN AND HIS CLASS/HERR BACHMANN UND SEINE KLASSE (2021)

HERR BACHMANN (CENTER) AND STUDENTS IN MR. BACHMANN AND HIS CLASS

TRAILER I

TRAILER II

Film about a small-town German 6th grade class of immigrant kids seems too long, but then you don't want it to end

Mr. Bachmann and His Class reminded me of the Belfast headmaster depicted in Young Plato. Kevin Mc Arevey in conflict resolution keeps it firm, but light. Herr Bachmann, who's different, because we see him mostly sitting in a classroom, and his class is as diverse as the Belfast school's is uniform, has a similarly firm and confident way of approaching his young charges; but his tone is on a lower register. Perhaps he's sad because he's retiring.

And that brings to mind another documentary, Nicolas Philibert's 2002 To Be and To Have/Être et avoir, also about a teacher on the brink of retirement, but with a one-room school of rural kids age 4-11, which I reviewed in a reserved way but lingers on as easily one of the greatest films about schoolteaching I've ever seen. Together with Nathaniel Kahn's 2003 search for his father My Architect, it's one of a tiny handful of my favorite docs of the last 25 years.

But Mr. Bachmann isn't in this category also because at over three hours, it seems not so much a documentary feature as a fragment of a mini-series. One understands the length, but does not condone it. Editing can shape a film artistically and clarify its meaning for the audience.

One can sympathize, of course. Herr Bachmann has spent hundreds of hours with the class: how can all that time be captured in 90 minutes? It's not a big class but they represent 12 or 13 countries, including Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Azerbaijan and Morocco, and they're adorable. Also well behaved. This is Europe, not America, they wear low-keyed clothes eschewing the latest hip hop fashions and they don't engage in self-indulgent shout-fests. It takes a while to get to know them. Unlike To Be and To Have, the film doesn't show us what any of their home lives are like.

Mr. Bachmann, like those other two teachers, remains a bit of a mystery, but he goes into more detail than they in a chat with a colleague about how he entered teaching (as a latecomer, originally a sculptor and sociology student forced into teaching by a need to pay the bills), and another with the student, Hassan, about how his parents worked all the time and had alcohol problems so he stayed away and played soccer. Now he's bohemian in spirit, with a whole wardrobe of knit caps and hooded sweatshirts, jocular and artistic. As A.O. Scott says in a recent NYTimes review, Bachmann is a somewhat unorthodox teacher whose "anarchist streak" makes him "a benevolent authority figure," but he is no less the disciplinarian ("Herr" Bachmann, after all), not "soft or lenient" or treating the kids "as friends or peers" but rather "as people whose entitlement to dignity and respect is absolute." At this age level striking such a subtle balance is one of the keys to being a great teacher.

What sets him apart is that while Bachmann teaches various subjects, he's also and most appealingly for the kids, a musician, singer and guitarist; and sometimes his classroom morphs into an art or rehearsal studio, with this well-endowed German school providing microphone, amplifiers and speakers, and various instruments. There is also a couch in the room. When the whole class goes on a holiday trip, Hassan gets a birthday celebration and is given a guitar as a present - how does Herr B. manage that?

The class becomes like a family, and even a very shy boy seems at home. Rabbia, who wanted to leave, has now fought with her family to keep them from moving away. She is not the first or only student to bloom, though the subtitles show us that German language skills of some have a way to go. There are other teachers of the class. Miss Bal is a woman of Turkish origin though she's been in Germany for 30 years. She may understand the class even better in Bachmann (but he shares their poor, working class origins). She gets pregnant and will be gone for those who come back to the 7th grade. They kiss and hug her saying goodbye.

Bachmann obviously likes his students and they like him. But though he professes to hate grading and get upset by it, he grades with a German ruthlessness. You see the logic of that. He has to decide where each student is going next: stay at this level, go on to secondary school (Realschule), or enter high school (Gymnasium). Because they are immigrant kids at various levels of learning German as well as levels of academic ability, Bachmann would not be doing a favor in sending a boy or girl to a class they're not ready for, to flounder or be sent back.

This school is in the town of Stadtallendorf an hour north of Frankfort. Once rural it was made industrial by the Nazis as the site of forced labor camps producing munitions under conditions dangerous as well as cruel. After the war the factories were repurposed and "Guest Workers," many Turkish, were brought in - giving a chilling cast to the Gastarbeiters concept. The kids are taught about this history in film, field trip, and lecture.

This school is free of some constraints of American ones. It's okay for teachers to touch or hug students. Bachmann talks and sings songs that introduce swear words or sexual references. He sings a song that's a ballad of a tragic gay love. One might question his having Ferhan, a big, sad veiled girl having trouble with German, to read a rather unclear story she has written about cats and dogs aloud to the class, and then to discuss its pros and cons at length with students. (But despite how it looks, this could have built Ferhan's confidence.)

Mr. Bachmann and His Class/Herr Bachmann und seine Klasse, 3h 37m, has had a rich festival life, with 26 listings on IMDb. It technically debuted at Hong Kong Apr. 5, 2021, but importantly at the Berlinale Jun. 17 it won director Maria Speth the Competition Audience Award and Silver Bear Jury Prize with a Golden Bear nomination. Its US fest debut was DOC NYC Nov. 10, 2021. It released Sept. 17, 2021 in Germany, and the week of Feb. 21, 2022 in the US. It is available streaming on MUBI. Metacritic rating: 92%.

HERR BACHMANN (LEFT) WITH HASSAN, RABBIA, JAIME, AYMAN, GENGISKHAN ET AL. IN HIS CLASS

STEPHI (RIGHT)

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 03-08-2022 at 07:40 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks