-

WHITE NOISE (Noah Baumbach 2022)

NOAH BAUMBACH: WHITE NOISE (2022

Baumbach goes big

The obvious link of White Noise with Noah Baumbach's first film, The Squid and the Whale (NYFF 2005), is the pretentious academic father, and the questioning children. But in other ways this bold, risk-taking new venture is another big step forward, as Noah Baumbach's terrific last film, Marriage Story (NYFF 2019), also was. This is the writer-director's first adaptation, and it's of a famous novel by Don DeLillo from 1985, also his first movie made on such a grand scale and with such a big budget and with such wild comic absurdity. It could be a grandiose failure: White Noise has for forty years been considered unfilmable. Welll, he's done it, and while not all of it works, especially not the last part, it was worth it. And I'd advise you to get on Netflix and enjoy it.

There are delights and complexities here never seen in a Noah Baumbach movie. This is the kind of picture you want to go back to. There's a lot going on and so much of it is rich and fun. The cynicism and satire and self-congratulatory cleverness of DeLillo's novel are all there - but with them a touching warm-heartedness and a caring about a family and a marriage we've never seen before in the director. Robbe Collin of the Daily Telegraph aptly describes White Noise as akin to "an early Steven Spielberg film having a nervous breakdown" and its frequent overlapping-dialogue passages have widely been linked to Robert Altman's style. But above all it's Don DeLillo, filtered, some think brilliantly, some think not enough, through the sensibility of Noah Baumbach.

The story is hard to summarize. It's about a lot of stuff, from messy families to academic pretension to toxic waste and environmental degradation to - the big one - fear of death. Things revolve around a small college in Ohio where J.A.C. Gladney (Adam Driver, with a paunch), known as Jack, is a professor of Hitler Studies who can't speak German, but is nonetheless widely celebrated for his theories, which delve into power and fame and the oddities of personal development - that Hitler was a mamma's boy and studied art - and overlook the Holocaust. Jack lives with Babette (Greta Gerwig, curly-blonde mophead), aka Baba, who teaches physical therapy. They have four children (all excellent), three by previous marriages (both are on their fourth), one, little Wilder (Henry and Dean Moore), their own.

Jack has several colleagues, the important one Murray Siskind (a droll Don Cheadle) is a professor who likes to talk about films of accidents and car crashes, and celebrates them as symbolic of American optimism. The satire of Eighties academic pretension flows freely. A whole lot else is going on in the thee-part division of the novel, first of all centering on the "airborne toxic event," then "Dylar," an experimental drug to ease fear of death (but with dire side-effects, like inability to distinguish words from things), then a crazy-fantastic finale with philosophical explorations that don't work but whose botched revenge-murder reminds me of Peter Sellers brilliant improvised finale for Kubrick's Lolita.. All through there is a return to a big supermarket as the place these consumer-crazed citizens take refuge in, with a glorious musical finale in the big A&P over the closing credits. The last section makes hilarious use of two excellent German actors, Barbara Sukowa as Sister Hermann Marie and Lars Eidinger as Mr. Gray.

The CGI and crowd-wrangling and disaster-staging are all new and great fun for a director who dealt in intimacy and family relationships before this. The gigantic crash of a big rig tanker truck driven by a drunk and loaded with gasoline into a train carrying toxic chemicals is the central event you've got to stage big-time, and Bauambach does it very nicely indeed: the black cloud of the pricelessly entitled "airborne toxic event" is in fact gorgeous. So also in their way are the car lineups and Eighties actioner-style backup crashes into metal garbage cans, the station wagon floating down the river with the Gladneys in it, the public and private voices fumbling and reshuffling advice and cover stories, just like Covid, as has been widely commented. This is the time when Sam Nivola shines as son Heinrich, the adolescent's rationality setting off Jack's uselessness and denial.

It's been a criticism of this precisely period mid-Eighties film that it's simply dated, and it's also been praised for getting the period just right, and achieving special relevance right now. It's all a bit true and who knows how this movie will age? It may be never better than right now. But it's also going to be fun in future watchings to w0rk out how the film's improvisations extrapolate and translate DeLillo's novel in movie form. It's enjoyable to see how - this comes in the Sam Nivola part - the satire on intellectual fakery indirectly celebrates intelligence. The last part isn't a success but the warmth and sympathy for this couple only grows. Baumbach strongly anchors DeLillo's picture of American's disquietude (their inability to find comfort or escape their mortality through their things and gadgets, in Driver's and Gerwig's humanness. This is a story/book that's mean and nasty and cynical but has a strong thread of love in it. It's this complexity that makes Baumbach's White Noise curiously endearing and memorable. The critical response has been mixed, reflected in a Metacritc rating of only 66%. But I can see why Mike D'Angelo in his "Year in Review" on Patreon makes this film his no. 5 of 10 but also mentions it as the "Outlier' and "Most Underrated," "the finest direction of Baumbach's career" and the movie he's currently most ready to go back to and resample.

White Noise, 136 mins., premiered at Venice Aug. 31, 2022 and debuted in the US in the New York Film Festival as the Opening Night Film Sept. 30 and showed at a dozen other festivals including London, Tokyo, Miami and Lisbon. Limited US theatrical release Nov. 25. From Netflix, US streaming release Dec. 30. Screened for this review online Jan. 1, 2023. Metacritic rating: 66%. AlloCiné press rating 3.7 (74%).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-02-2023 at 06:56 PM.

-

DAVY CHOU: RETURN TO SEOUL/RETOUR À SÉOUL (2022)

PARK JI-MIN IN RETURN TO SEOUL Thomas Favel/Aurora Films/Sony Pictures Classics

An aggressive search for identity

When Koreans drink together (as they do a lot: watch any Hong Sang-soo film), it's the custom that they pour each other's soju or whatever reciprocally into each other's glasses, never straight into their own. When Frédérique Benoit (Park Ji-min), AKA Freddie, is told this, she grabs the bottle, pours the soju into her own glass, and chugs it. Who does that? This behavior turned me against Freddie from the start. It took most of the movie to win it grudgingly back.

Freddie was born in Korea, adopted by a French couple and raised as French. (Her birth name is revealed to be Yeon-Mi, meaning "docile and joyful,' a rather obvious irony.) Now 25, she is visiting Seoul for the first time since infancy, basically on a whim. She likes vacationing in Japan, we learn later in a Skype conversation with her mother, but many flights were cancelled for a typhoon, she wanted to go somewhere, so here she is.

Her mother had so much wanted to go with her, and is very disappointed. But impulsiveness is the rule with this young woman, who is pretty and vibrant, but also obnoxious and confrontational. She is so outside the norm in the Korean bar, accompanied by Tena (Guka Han), the timid French-speaking acquaintance from the hostel where she's staying who acts as her mollifying French-Korean interpreter, that her presence must be electrifying. One baby-faced boy is attracted to her and she sleeps with him. The next morning the naive, dazzled kid wants to be hers forever. She tells him to get lost. Later there is Maxime (Yoann Zimmer), a French boy she's actually been going around with she tells: "I can erase you from my life with the snap of a finger." Nice.

Director Chou, who is French-Cambodian and reports he was inspired to make this picture by the experience of a friend, may have also worked off the personality of first-time actress Park Ji-min, whose energy, charisma, and sexiness are admittedly compelling and help fill in gaps in the writing. The experience of coming back to Korea and seeking out one's birth relatives through the adoption agency can feel momentous but also painful and tedious, as was shown in Malene Choi's The Return (NYAFF 2018), which mixed documentary and fictionalized elements to show what happens to several returned young Korean adoptees. It has to be done, but do we need to be the audience for it?

This issue eventually is avoided because this film, which has good tech credits and actors, is mainly a portrait of this eccentric, troubled young woman, with her adoptee story just a pretext. The score by Jérémie Arcache and Christophe Musset is rich and supple. It takes charge in that opening café scene when Freddie dances, "gyrating," Amy Nicholson says in her admiring New York Times review, "as through [she] doesn't care if she doesn't see anyone in Seoul ever again." The cinematography by Thomas Favel shines with deep glowing colors and pleasing bluish blurs in the Seoul nightclub scenes. But Freddie will soon go through the Hammond adoption agency and meet with her biological father, played by Oh Kwang-rok, an air conditioning repairman with an extended family.

Her father like Freddie behaves wildly when drunk, and is prone later on in the relationship to nagging, maudlin expressions of guilt and a desire to control. Right off he tells her, through timid Tena, that he wants her to live in Korea and he will find her a husband. As Nicholson puts it, the early encounter with him "feels both momentous and aggressively dull."

The "momentous" but "aggressively dull" aspect of Korean adoptee-reunion stories is escaped by this film's odd structure and its focus on the attention-getting personality of Freddie. Return to Seoul makes repeated sudden, clear-cut several-year leaps forward, taking us all told into Freddie's early thirties. It shows her only in Korea and briefly at film's end in Romania on a hike and hotel stay identified only in the closing credits. There is nothing about her life before in France. As we progress, Freddie changes, but not in clear-cut or progressive ways. Her relation with her birth father and his family continues, with her relying on some Korean she has finally learned and on English as a lingua franca. Now she is doing some kind of international work. Later she is on a computer date with an older man called André (Louis-Do de Lencquesaing of Mia Hansen-Løve's Le père de mes enfants), who tells her he is in the arms business and she would be great in it "Because you have to be able to not look back."

By this time she has lipstick smeared on and hair pushed down: it's not such a great look, but it's a change. Later, she meets with her Korean dad's people once again (Oh Kwang-rok, who had minor roles in Park Chan-wook's "Vengeance" trilogy, is a vivid actor) and tells them she is now, in fact, indirectly in the "defense" business for Korea.

Over several years she continues trying to make contact through the adoption agency with her birth mother. And this momentous, nearly wordless event finally does take place at the agency itself, in a safe, careful ritual that is very well acted out and reproduced in this film. This is a hushed, memorable scene, photographed very close without clearly showing the mother. Freddie is at last subdued by the momentousness of the reconnection.

Some have showered Return to Seoul with superlatives. It feels as though Chou has let his lead actress run away with it somewhat. But in the times when it and she calm down, the initial aggressiveness and offense fade into an intriguing mystery so one admits this director may know how to make movies (his two previous ones have won awards).

Director Chou has certainly gotten around the "aggressive boredom" of discovering that the Korean adoptee has (in the Times reviewer's words) "been robbed of a life she doesn't actually want to live." What most of all seems to attract Freddie to Korea, as Boyd van Hoeij suggests in his The Verdict review, is that it's so easy for her to shock people there, looking like a local and yet acting so different, "simply by saying something that goes against the grain or would be considered not done." But despite the vivid performances, nice score, and beautiful cinematography, the jumps forward are hard to parse and Freddie's unclear development make the film for van Hoeij "feel long and repetitive" and "the lead character is just too exhausting to watch." I agree: Return to Seoul is an uneven watch. There is fascination and elegance here, but there is also that. Wendy Ide wrote in Screen Daily that the film "is unconventional and at times abrasive" but has "a seductive, searching quality" and "a swell of melancholy" which makes for "an engaging, if unpredictable journey." It has been well marketed and well received. Not everyone will like it. My jury is still out.

Return to Seoul/Retour à Séoul, 115 mins., debuted at Cannes in Un Certain Regard May 22, 2022. (A previous Chou film won a prize at Critics Week in 2016.) Over 44 international festivals listed on IMDb including Toronto Sept. 8 and New York Oct. 13. Cambodia's entry for Best International Oscar entry. Metacritic rating: 88%. Opens (Sony Pictures Classics) New York and Los Angeles Feb. 17, 2023.

-

SAINT OMER (Mati Diop 2022)

MATI DIOP: SAINT OMER (2022)

GUSLAGIE MALANDA IN SAINT OMER

Mati Diop's impressive but frustrating first fiction feature arouses more questions than it answers

Saint Omer - well known 41-year-old Senegalese-French documentary filmmaker Mati Diop's first fiction feature - is drably titled: it's only the name of the town where the trial takes place. This is a minimalist kind of courtroom drama film. It presents only a handful of witnesses. Most of the talking is done by the judge, the defendant, and the defense lawyer. Most oddly, little light is shed upon the crime. Is this a trial at all? The defendant has already fully confessed to her premeditated crime of going from Paris to a small town and leaving her 15-month-old daughter on the beach to drown in the rising tide. Nonetheless in its patience-straining way, Saint Omer is riveting courtroom stuff. And then it frustrates us at the end by delivering a message but not a decision. Mati Diop is a tease. Did she learn from Claire Denis, a master of vivid withholding, while playing a major role in Denis' 35 Shots of Rum?

This film is maddening and irritating, yet has been heralded as innovative. It draws attention especially in its introduction of a central character, Rama (Kayije Kagame) who comes to observe, not participate, a teacher and successful novelist attending the trial with the intention of making it into her next novel (a publisher is lined up). She is a powerful figure (and Kagame has a dark, strong, intense presence) who is no less effective through being largely silent in some of the key shots of her. Rama is the audience representative and the stand-in for Mati Diop, the filmmaker, who attended the actual trial of Fabienne Kabou for infanticide on which Saint Omer is based. Skillful use is made of silent images of Rama, whose reactions - and identification - are intense. She connects with the accused's mother Odile Diatta (Salimata Kamate), meeting with her during the trial and lunching with her. All this is like Truman Capote being a major character of In Cold Blood. It's the much later legacy of the Me Journalism of the Seventies, I guess. At the outset of the trial, the judge orders all "journalists" to leave the courtroom. I kept wondering, why is a novelist planning a book and (as we see later) recording the proceedings on her smart phone, not excluded?

Even though, or rather because, she remains mysterious - most of all to herself - the accused Laurence Coly (Guslagie Malanda) remains the main character. Malanda, though as is noted is "invisible" and even is dressed and lit to seem to "disappear" into the background of the wood paneling behind her in the courtroom, speaks in a quiet, assured (even while expressing uncertainty, not knowing), holds our attention. Whois she, what is she? She has claimed sorcery and spells are behind her act. But the defense says she is deranged and needs treatment, not punishment. Much prior evidence emerging in what appears only to be part of her recorded testimony emphasizes that she is a habitual liar. Even she acknowledges this.

Arguably too much is made of Rama. As Anthony Lane notes in his New Yorker review, Laurence would have been interesting enough by herself. There is something naïve and factitious about showing Rama lecturing on Marguerite Duras and the passage in her script for Hiroshima Mon Amour elevating French women humiliated for having Nazi/German lovers to semi-martyr status, and watching Maria Callas as Medea in Pasolini's film, lifting child murder to the level of myth. Mati Diop's intense reaction to the trial, leading to this fiction, or fictionalized, film is explained by her actual multiple points of similarity with the accused: she too of Senegalese, mixed-race descent with a white boyfriend, and pregnant to boot. (In real life she reportedly had a small child, but making the child still in Rama's womb and her having nausea and discomfort adds a creepier, scarier note.)

What's interesting - what will be remembered about this film - is the mysteriousness and illogic or Laurance's answers to questions in the trial. She says early on she doesn't know why she murdered her child but hopes the trial will show her. She's smart, we're told, and speaks elegant French - though noting the latter too much, given that she's from Dakar, Senegal, will be taken as condescending, like the university prof. who testifies he advised her not to do a thesis on Wittgenstein but something more appropriate to her "culture."

A. lot of Laurence's testimony seems to be closely drawn from the actual Fabienne Kabou trial, but it seems calculated to make her even more puzzling than the original was. A 2016 Le Monde article about the final sentencing describes Fabienne: "One expected a woman drowned in solitude, abandoned to her torments of mother under the indifferent glance of her companion; one saw appearing a tough, authoritarian, deceitful and lying accused." Of her much older white companion, father of the baby, Luc Dumontet (Xavier Maly) in the film, the article says he "was seen at the beginning of the hearing as morally guilty and ... turned out to be the exact opposite of the portrait that had been drawn up[;] everyone had the feeling of having been deceived, betrayed by the accused." If this is true, this not the impression of the two the film leaves us with.

But the major point/criticism to be made is that Diop doesn't show us the results of the actual trial at all. You will learn from news stories that the defendant was sentenced to twenty years imprisonment, lowered to fifteen at appeal. All we get is the impassioned (and fanciful) summing up of the defense, Maître Vaudenay (Aurélia Petit). There is no summing up of the prosecution (Robert Cantarella), and no decision from the red-robed judge (Valérie Dréville) .

We have been held riveted for two hours, riveted and uncomfortable, and then we have been cheated. Is this a "new, innovative" variation on a trial movie or a perversion of one? Does Diop consider the French court system a racist, colonialist travesty? But that could be a dangerous assumption. Maybe you should see the film and decide for yourself, though.

Saint Omer, 122 mins., debuted at Venice Sept. 7, 2022, and was included in over two dozen international festivals including Toronto, New York, Busan and Vienna. French theatrical release Nov. 23, 2022. AllCiné press rating 4.2f (82%). US limited release Jan. 13, 2023. Screened for this review at AMC Bay Street Jan. 18, 2023. (Metacritic rating 90%).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-19-2023 at 12:44 AM.

-

SHAUMAK SEN: ALL THAT BREATHES (2022)

SALIK REHMAN IN ALL THAT BREATHES Credit: CitySpidey

"One shouldn't differentiate between all that breathes"

This is a remarkable documentary that, while appearing unpretentious and ordinary and really quite drab on the surface, unfolds entirely in its own way, with its own look, feel, edits, and rhythms and tinkly orchestral score. One doesn't even like to call it a "documentary." It's a film. It draws us into its world and in doing so it takes its time. Often a great documentary creeps up on you and must be a slow gathering of details, a gradual astonishment. So it is with All That Breathes. I had a sense that this would be special since missing it in the Main Slate of the New York Film Festival, and it turned out even better than expected.

All That Breathes is a film about three men in perhaps one of the worst parts of the city of Delhi. Brothers Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad, and Salik Rehman, their cousin who works with them are all of Muslim origin. Things are becoming discriminatory under the Hindu nationalist and increasingly dictatorial Narendra Modi and if they're outlawed, they muse, they haven't the credentials that would get them into Pakistan. Their life project is saving black kites. These birds replace vultures in consuming waste. Mountains of garbage would grow without them. More of them are falling from the sky: the air of Delhi is the most polluted in the world, for the birds, as for humans, increasingly unsustainable but it may be their numerousness and proximity to the millions of the city that is their undoing.

The brothers and sometimes grumpy with each other and break out in verbal battles. But they say it's not them. It's what's happening in the sky that causes these little fracases. Mostly they work peacefully together. They have done so since they were "teenage bodybuilders" and discovered the kites and their need for first aid, and they applied information on muscles and tendons they'd gathered that way to the muscles and tendons of the birds. As boys they'd been taken to throw meat to the kites by their father, and knew it was deemed good luck. As youths they'd rescued small animals but they gradually focused on kites because regular bird hospitals rejected them for being neat eaters. Now their bird hospital in incorporated as a charity called "Wildlife Rescue."

They also assemble soap dispensers for income, and the older brother, toward the end, goes to the States to study for a while, leaving brother and cousin to hold the fort till he returns. We have glimpsed and heard of violence and houses set afire quite nearby as well as demonstrations against violence. The brothers work on. Their urgent effort to save the kites is a still point of reason and wholeness in what we may dimly perceive as an apocalyptic and crumbling capitol city. A motif of the artfully askew All That Breathes is the oneness of men, and the unity of man and nature, which here seem both impossible, and inevitable. Beside a torn up street, a terrapin crawls. Along a flooded street, cattle walk. We even glimpse a wild pig. Nature is alive and well after all in this overpopulated city.

An unseen eye and an unseen voice and a camera that likes to slide slowly across a scene provide us with views of the brothers and their work surroundings. The first thing one may notice is hands holding one of the big birds and the firm, gentle, practiced touch. Placing the bird somewhere, carefully. Plying apart the feathers to examine a wound, a weak limb, a spot of blood.

Their digs are shabby but somehow cozy. The younger, thinner cousin, Salik Rehman, is on a balcony when a kite comes by and grabs his glasses. It flies off with them. It does not come back. He talks about those lost glasses for a while, rather to his cousin's annoyance. Another time two of the guys strip and swim out into the river to rescue a wounded kite that will be eaten shortly if they doh't save it. Nadeem Shehzad directs them. Surprisingly, the seemingly more fit Salik runs out of energy and panics, caught in the middle of the water. But they make it back.

As suggested, these activities in themselves may seem inconsequential, but it's the focus they show, and the patient rhythm. It turns out the black kites of Delhi are often injured by glass-coated strings used for the other, human, sort of kites, those flown in the air by people. The birds of prey have grown more numerous due to large slaughterhouses in the city. (I get this and much more from a copiously illustrated local article in CitySpidey. They are falling out of the sky in greater and greater numbers, but also this bird hospital is known to more and more people. Selek Rehman is bringing more and more of the cardboard boxes used to hold the sick or injured birds every day. A NYTimes article helps get more funding and a lovely white "open cage" up on the roof has been created.

The work at Wildlife Rescue strives for non-invasiveness, for preservation. The style of this film likewise is to help things along without ever seeming to intrude. It's an unusual combination, and the gentle tuning in to the naturalist's view is unusual too. All That Breathes lives up to that cliché: it takes you somewhere you've never been before. I wouldn't want to tell you too much about it, but there's no danger: no review can capture the unique style and mood of this lovely and thought-provoking film.

All That Breathes debuted at Sundance Jan. 2022 winning the grand jury documentary prize, and it went to Cannes, winning the the Golden Eye award. Numerous festivals, awards, and nominations followed. It will be released on HBO later in Jan. Metacritic rating: 86%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-24-2023 at 02:48 PM.

-

SHOWING UP (Kelly Reichardt 2022)

KELLY REICHARDT: SHOWING UP (2022)

MICHELLE WILLIAMS, HONG CHAU IN SHOWING UP

An artist prepares for her show

I previously wrote about Kelly Reichardt's Certain Women (2016-NYFF): "If Reichardt achieves authenticity and a sense of real time in these sad, dreary tales, there's also a lack of economy and a lack of verve, almost a stubborn clumsiness. And so this time it's tempting to side somewhat with Rex Reed in the Observer, who commends the acting in this film but condemns Reichardt's style. "Nothing ever happens in her movies," Reed says, "but a handful of critics rave, they end up on the overstuffed programs at film festivals like Sundance and are never seen or heard from again." That isn't really true. But this is a failed movie with one powerful thread, and I wish Reichardt's 2014 Night Moves had gotten all the attention that her 2010 Meek's Cutoff did."

This is the way it has gone for me, perhaps for others. Reichardt is a significant American auteur. Ever since what technically may have been her third film (2006), Old Joy (though nobody saw the first two), critics and cinephiles have had a lot of time for Reichardt's films, even when they were very often stubborn and resisted attention. There are only half a dozen, but have appeared regularly, mostly at three-year intervals; this new one shows no delay from the pandemic. All have stayed in the mind, nagged like Meek's Cutoff, excited like Night Moves, even touched like First Cow. The new one nags, bores, and annoys, but it won't go away. And though one strains to see why Reichardt wanted to make it, its realness leaves one impressed. It's a vivid slice of life. Was it worth slicing? Maybe here there is a lot about today's minor, struggling artist that is so specific it could wind up being enlightening.

Though sharing qualities of being stubborn, specific, and resisting conventional rewards, Reichardt's films have gone in different directions. She has shown a gift for carefully researched and offbeat dips back into early nineteenth-century America with the 1845-set western-traveling Meeks Cutoff and the 1820 pre-Oregon First Cow - the first hard to take, the second hard to resist. This time she doesn't go far: Oregon and art. (She has taught film for some years at Bard, in Annandale-On-Hudson, New York, a school with a strong art focus. Most of her films have been shot in Oregon.) The protagonist of Showing Up is a grumpy, dumpy single woman artist, Lizzy (Michelle Williams in her fourth Reichardt joint) preparing for a show of her small baked figurative sculptures while dealing with "the daily dramas of family and friends."

Léa Seydoux also drabbed-down for her lead in Mia Hansen-Løve's recent One Fine Morning. But with Léa, the radient beauty shines through. Michelle's doesn't: she loses herself in unappealing, unfriendly Lizzy. She doesn't seem to look at us, or anybody. She looks at, and touches, almost caresses those odd sculptures of hers (actually made by the Portland-based artist Cynthia Lahti). They are about two feet tall, or less, of women contorted or gesturing extravagantly. An extreme, expressionistic outgrowth of the school of Rodin, they seem unfashionable, out of date (who makes figurative sculptures anymore?). Isn't this part of the point? Though she doesn't quite say it, Lizzy probably doesn't expect her sculptures to be appreciated.

Lizzy grouses most of all with Jo (Oscar-nominated Hong Chau), her neighbor and negligent landlady, since the latter is s taking weeks to repair Lizzy's water heater. But Jo's an artist too - her work is big and colorful; we glimpse it - and has two shows coming up. Both are connected with a local Portland art school; Jo teaches, Lizzy works in an office, her mother the director. Jo points out her rent is low. She hasn't got it too hard. Her sculptures get baked in a kiln at the school by a friendly, cheerful guy, Eric (André Benjamin). Her father (the resurgent Judd Hirsch again), himself a potter, now, he insists, retired (his work looks handsome), is sprightly and cheerful.

Who arguably doesn't have things so good is Sean (John Magaro, who played the lead role of Cookie in First Cow), Lizzy's brother, who's an artist too. Lizzy may think her parents considered him more talented than she, but he has fairly serious mental issues; his behavior is unpredictable, and he's certainly not happy.

All this is what Showing Up is "about" - along with the obvious MacGuffin of a wounded pigeon Lizzy's cat brings in that she and Jo wind up trading places in caring for. The beauty of the film is how spot-on all the details are. But while Kelly Reichardt films have been fights for survival, the urgency level here is like, whether there is too much cheese on the table at Lizzy's show reception, and then, whether her crazy brother will eat it all up.

Showing Up, 107 mins., debuted in Competition at Cannes May 27, 2022, also in the Main Slate of the NYFF Oct. 5 and shown in a dozen other international festivals. US theatrical release by A24 April. 7, 2023. Metacritic rating 84%. Surprisingly, Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle gave it a rave. He always seemed to hate everything and have very conventional tastes. Screened for this review at Landmark Albany Twin April 28, 2023.

-

NO BEARS (Jafar Pqnahi 2022)

JAFAR PANAHI: NO BEARS (2022)

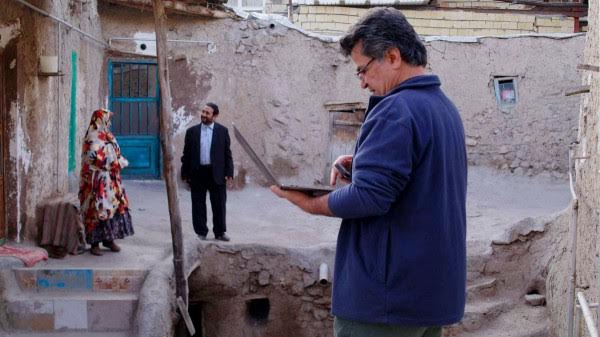

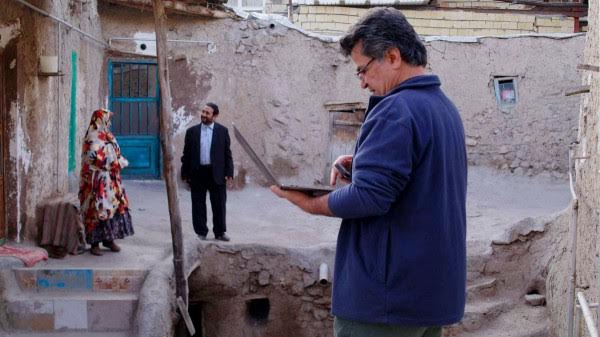

JAFAR PANAHI (RIGHT) IN NO BEARS

The oppressed Iranian filmmaker's fifth clandestine film is a dry multi-layered puzzler

I wonder how Pauline Kael would have reviewed the films of Jafar Panahi, Iran's most famous filmmaker. She did have the balls to pan a sacred cow of a film like the exhausting Holocaust documentary Shoah. Panahi too is a sacred cow. He, or the character with his name in his latest film, No Bears, the fifth made clandestinely since he was forbidden by the government to make films, is a muted, ironic figure, the tight-lipped protagonist, the understated star of his own work. Jafar Panahi is a real life hero. Despite imprisonment, house arrest, and being banned in 2010 from making films for 20 years, he has managed to go on making them, and refuses to leave the country. But when he is showered with praise, how much can we separate the filmmaking from his well-deserved glow as a hero of artistic resistance to the oppressive regime of the mullahs?

Maybe Jafar Panahi's films could be more entertaining. It might seem impossible to make a fun movie about an oppressive country like Iran, but this was disproved last year when Panahi's own son, Panah Panahi, released his first feature, the hilarious, stimulating, meaningful and sad Hit the Road. His father Jafar's new one is many-layered and complex in ways that reviewers are delighted to parse. It offers rewards for seasoned fans. But its entertainment is of a very dry and subtle sort, if entertainment there is.

Nonetheless No Bears, which shows Jafar Panahi, or "Jafar Panahi," struggling to direct a film remotely from an Iranian village near the Turkish border, where the cast and crew are, is an impressively smart and understated film. Its blending of fiction and documentary elements is a feature of the director's style that goes back to his first work. For example, a clip he shows in This Is Not a Film records a girl being filmed on a bus who tears off a fake leg cast yelling that she refuses to participate in this charade. This is essentially what a couple does in No Bears: they are playing a version of themselves (or their film selves), a dissident couple, Zara (Mina Kavani) and Bakhtiar (Bakhtiar Penjei), who have escaped the country, but the wife protests that the in-film version they're being asked to enact is a whitewashed image of her far worse sufferings in ten years of struggle and she won't go on with it. Is this outburst true to life, or is it the fiction? We don't know.

This film has been described as revolving around "two parallel love stories." The first involves the troubled mature couple in the film-within-the-film who are, or were, seeking to escape the country. The other is a young couple in the village "Panahi" is staying in, Gozbal (Darya Alei) and Soldooz (Amir Davari). Accused of holding back a photo on a digital disc depicting a couple said to be in love, while the girl is being set up for arranged marriage to another, the No Bears "Panahi" denies that he made any such photo. He is asked by the village chief (Naser Hashemi) to go to a place called "the oath room" where he will swear to this, but he is assured parenthetically that this place is just a village tradition, and it is "okay to lie." That kind of says it all: this is a country where oaths and morality are a big deal, but lying is a common, assumed practice.

The interest, the dry fun, of No Bears is its confusing mix of urban and rural and of documentary and fiction. It is all fiction: the "real" "Jafar Panahi" seen here is a bit less like the "real" Jafar Panahi than in his previous four clandestine films. He is not making this film about the couple seeking to escape the country, but a film about making such a film. In the meantime there is much static from the "actual" location, where "Panahi" is, a small village (not actually where it's said to be). "Panahi" is renting a large room in the village, but his "host" is constantly looking for excuses to make him leave. There is trouble in the village, the fracas over the contested wedding, and "Panahi" is in the middle of it because of allegedly having photographed the would-be "bride" with her real "lover." A little boy claims when "Panahi" was taking his picture with several other boys, he saw "Panahi" photograph the couple. There is also more commonplace buffoonery of a sort Panahi seems to like now, when "Panahi" must climb a ladder trying to connect with wi-fi (the reviewer for Slant has said this is a ripoff from Kiarostami). All the sophistication of good digital cameras, slim laptops and smartphone, clashes with the rustic walls, obligatory glasses of tea, and the feeble wi-fi of a village.

This contrast between the primitive and the modern is in your face here. The village is rife with "traditions" and rigid conventions about marriage. The old ladies serving "Panahi" provide excellent cooking, but with the shaky internet, the rental "host" a constant annoyance and the challenged would-be groom in a constant menacing rage, disorder is just round the corner. The latter individual delivers a prolonged rant in the "oath room" scene that illustrates something Iranians in films often seem to excel at: orally haranguing and abusing each other.

But the urban, and urbane, "Panahi" never loses his cool. His dry restraint stands as a reproach to all the misbehavior and his own mistreatment. He stands aloof; and beyond that lurks the courage of the real filmmaker who has endured so much harassment from the Iranian government and remained productive through it all - though post-No Bears, he was in prison again, initially along with the other top Iranian filmmaker, Mohammad Rasoulof (the third is Asghar Farhadi). (In early Feb. 2023 he was released from prison.)

Panahi's first clandestine film, the 2011 This Is Not a Film, was smuggled out of the country on a flash drive in a loaf of bread and shown at Cannes, the New York Film Festival (where I reviewed it), and in forty other festivals, winding up on many best movie or best documentary lists. The subsequent three and this one have likewise received top honors from critics and festivals. Mohammad Rasoulof was recently on the Venice jury. This in part is a triumph of digital technology and the internet, also celebrated indirectly in No Bears, with "Jafar Panahi" directing a film from across the Turkish-Iranian border, which dramatically he refuses to cross.

The title No Bears, is symbolic of a rejection of naïve village traditions embracing ignorance. The village chief talks about the danger of bears to "Panahi," but then says the menace of the ursine critters is only a superstition: there are "no bears." Martin Luther King famously declared that "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." Hopefully it bends toward rationality and artistic freedom too, even in Iran. But there is more gloom than hope in No Bears. Jessica Kiang wrote in her Variety review that where his earlier clandestine films celebrated "the liberating power of cinema," this is a darker one where Panahi "slams on the brakes." In his Slant review Sam C. Mac, noting the devotion to "meta" in Panahi shows his debt to his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, points to what is also my main objection in No Bears: that it's overburdened by an "increasingly convoluted plot" developed to illustrate its themes, and is not, despite what some critics have said, as visually interesting as his other recent films. But it is part of an œuvre that we cannot overlook.

No Bears 106 mins., in Farsi (Farsi title خرس نیست/Khers Nist), debuted at Venice Sept. 9, 2022 and was shown in about 50 other international festivals, including Toronto and New York. Its official US theatrical release was Dec. 23, 2022 in New York City (Film Forum). It premiered on the Criterion Channel Apr. 18, 2023, where it was screened for this review.

-

Metascores of the 2022 nyff main slate

Metacritic ratings of NYFF 2022 Films and links to reviews

Opening Night

“White Noise”

Dir. Noah Baumbach

Metacritic: 66%

Centerpiece

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”

Dir. Laura Poitras

Metacritic: 90%

Closing Night

“The Inspection”

Dir. Elegance Bratton

Metacritic: 73%

NYFF 60th Anniversary Celebration

“Armageddon Time”

Dir. James Gray

Metacritic: 74%

“Aftersun”

Dir. Charlotte Wells

Metacritic: 95%

“Alcarràs”

Dir. Carla Simón

Metacritic: 85%

“All That Breathes”

Dir. Shaunak Sen

Metacritic: 87%

“Corsage”

Dir. Marie Kreutzer

Metacritic: 76%

“A Couple”

Dir. Frederick Wiseman

Metacritic: 74%

“De Humani Corporis Fabrica”

Dir. Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor

Metacritic: 90%

“Decision to Leave”

Dir. Park Chan-wook

Metacritic: 84%

“Descendant”

Dir. Margaret Brown

Metacritic: 87%

“Enys Men”

Dir. Mark Jenkin

Metacritic: 77%

“EO”

Dir. Jerzy Skolimowski

Metacritic: 85%

“The Eternal Daughter”

Dir. Joanna Hogg

Metacritic: 80%

“Master Gardener”

Dir. Paul Schrader

Metacritic: 59

“No Bears”

Dir. Jafar Panahi

Metacritic: 92%

“The Novelist’s Film”

Dir. Hong Sangsoo

Metacritic: 82%

“One Fine Morning”

Dir. Mia Hansen-Løve

Metacritic: 85%

“Pacifiction”

Dir. Albert Serra

Metacritic: 79%

“R.M.N.”

Dir. Cristian Mungiu

Metacritic: 75%

“Return to Seoul”

Dir. Davy Chou

Metacritic: 88%

“Saint Omer”

Dir. Alice Diop

Metacritic: 91%

“Scarlet”

Dir. Pietro Marcello

Metacritic: 69%

“Showing Up”

Dir. Kelly Reichardt

Metacritic: 81%

“Stars at Noon”

Dir. Claire Denis

Metacritic: 64%

“Stonewalling”

Dir. Huang Ji and Ryuji Otsuka

Metacritic: 84%

“TÁR”

Dir. Todd Field

Metacritic: 92%

“Trenque Lauquen”

Dir. Laura Citarella

Metacritic: tbd

“Triangle of Sadness”

Dir. Ruben Östlund

Metacritic: 63%

“Unrest”

Dir. Cyril Schäublin

Metacritic: tbd

“Walk Up”

Dir. Hong Sangsoo

Metacritic: 86%

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-27-2023 at 06:22 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks