-

PARASITE (Bong Joon-ho 2019)

BONG JOON-HO: PARASITE 기생충 (Gisaengchung) (2019)

LEE SON-KYUN AND JO YEO-JEONG IN PARASITE

Crime thriller as social commentary? Maybe not.

I've reviewed Bong's 2006 The Host ("a monster movie with a populist heart and political overtones that's great fun to watch") and his 2009 Mother which I commented had "too many surprises." (I also reviewed his 2013 Snowpiercer.) Nothing is different here except this seems to be being taken more seriously as social commentary, though it's primarily an elaborately plotted and cunningly realized violent triller, as well a monster movie where the monsters are human. It's also marred by being over long and over-plotted, making its high praise seem a bit excessive.

This new film, Bong's first in a while made at home and playing with national social issues, is about a deceitful poor family that infiltrates a rich one. It won the top award at Cannes in May 2019, just a year after the Japanese Koreeda's (more subtle and more humanistic) Palm winner about the related theme of a crooked poor family. Parasite has led to different comparisons, such as Losey's The Servant and Pasolini's Theorem. In accepting the prize, Bong himself gave a nod to Hitchcock and Chabrol. Parasite has met with nearly universal acclaim, though some critics feel it is longer and more complicated than necessary and crude in its social commentary, if its contrasting families really adds up to that. The film is brilliantly done and exquisitely entertaining half the way. Then it runs on too long and acquires an unwieldiness that makes it surprisingly flawed for a film so heaped with praise.

It's strange to compare Parasite with Losey's The Servant, in which Dick Bogarde and James Fox deliver immensely rich performances. Losey's film is a thrillingly slow-burn, subtle depiction of class interpenetration, really a psychological study that works with class, not a pointed statement about class itself. It's impossible to speak of The Servant and Parasite in the same breath.

In Parasite one can't help but enjoy the ultra-rich family's museum-piece modernist house, the score, and the way the actors are handled, but one keeps coming back to the fact that as Steven Dalton simply puts it in his Cannes Hollywood Reporter review, Parasite is "cumbersomely plotted" and "heavy-handed in its social commentary." Yet I had to go to that extremist and contrarian Armond White in National Review for a real voice of dissent. I don't agree with White's politics or his belief that Stephen Chow is a master filmmaker, but I do sympathize with being out-of-tune, like him, with all the praise of Boon's new film.

The contrast between the poor and rich family is blunt indeed, but the posh Park family doesn't seem unsubtly depicted: they're absurdly overprivileged, but don't come off as bad people. Note the con-artist Kim family's acknowledgement of this, and the mother's claim that being rich allows you to be nice, that money is like an iron that smooths out the wrinkles. This doesn't seem to be about that, mainly. It's an ingeniously twisted story of a dangerous game, and a very wicked one. Planting panties in the car to mark the chauffeur as a sexual miscreant and get him fired: not nice. Stimulating the existing housekeeper's allergy and then claiming she has TB so she'll be asked to leave: dirty pool. Not to mention before that, bringing in the sister as somebody else's highly trained art therapist relative, when all the documents are forged and the "expertise" is cribbed off the internet: standard con artistry.

The point is that the whole Kim family makes its way into the Park family's employ and intimate lives, but it is essential that they conceal that they are in any way related to each other. What Bong and his co-writer Jin Won Han are after is the depiction of a dangerous con game, motivated by poverty and greed, that titillates us with the growing risk of exposure. The film's scene-setting of the house and family is exquisite. The extraordinary house is allowed to do most of the talking. The rich family and the housekeeper are sketched in with a few deft stokes. One's only problem is first, the notion that this embodies socioeconomic commentary, and second, the overreach of the way the situation is played out, with one unnecessary coda after another till every possibility is exhausted. This is watchable and entertaining (till it's not), but it's not the stuff of a top award.

Parasite 기생충 (Gisaengchung), 132 mins., debuted in Competition at Cannes, winning the Palme d'Or best picture award. Twenty-eight other festivals followed as listed on IMDb, including New York, for which it was screened (at IFC Center Oct. 11, 2019) for the present review. Current Metascore 95%. It has opened in various countries including France, where the AlloCiné press rating soared to 4.8.

PARK SO-DAM AND CHOI WOO-SIK IN PARASITE

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-19-2020 at 01:49 AM.

-

MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN (Edward Norton 2019)

EDWARD NORTON: MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN (2019)

GUGU MBATHA-RAW AND EDWARD NORTON IN MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN

Edward Norton's passion project complicates the Jonathan Lethem novel

The NYFF Closing Night film is the premiere of Edwards Norton's adaptation, a triumph over many creative obstacles through a nine-year development time, of Jonathan Lethem's 1999 eponymous novel. It concerns Lionel Essrog (played by Norton), a man with Tourette's Syndrome who gets entangled in a police investigation using the obsessive and retentive mind that comes with his condition to solve the mystery. Much of the film, especially the first half, is dominated by Lionel's jerky motions and odd repetitive outbursts, for which he continually apologizes. Strange hero, but Lethem's creation. To go with the novel's evocation of Maltese Falcon style noir flavor, Norton has recast it from modern times to the Fifties.

Leading cast members, besides Norton himself, are Willem Dafoe, Bruce Willis, Alec Baldwin, Cherry Jones, Bobby Cannavale and Gugu Mbatha-Raw. In his recasting of the novel, as Peter Debruge explains in his Variety review, Norton makes as much use of Robert Caro's The Power Broker, about the manipulative city planner Robert Moses, a "visionary" insensitive to minorities and the poor, as of Lethem's book. Alec Baldwn's "Moses Randolph" role represents the film's Robert Moses character, who is added into the world of the original novel.

Some of the plot line may become obscure in the alternating sources of the film. But clearly Lionel Essrog, whose nervous sensibility hovers over things in Norton's voiceover, is a handicapped man with an extra ability who's one of four orphans from Saint Vincent's Orphanage in Brooklyn saved by Frank Minna (Bruce Willis), who runs a detective agency. When Minna is offed by the Mob in the opening minutes of the movie, Lionel goes chasing. Then he learns city bosses had a hand, and want to repress his efforts.

Gugu Mbatha-Raw's character, Laura Rose, who becomes a kind of love interest for Lionel Essrog, and likewise willem Dafoe's, Paul Randolph, Moses' brother and opponent, are additional key characters in the film not in the Johathan Lethem book. The cinematography is by the Mike Leigh regular (who produced the exquisite Turner), Dick Pope. He provides a lush, classic look.

Viewers will have to decide if this mixture of novel, non-fiction book and period recasting works for them or not. For many the problem is inherent in the Lethem novel, that it's a detective story where, as the original Times reviewer Albert Mobilio said, "solving the crime is beside the point." Certainly Norton has created a rich mixture, and this is a "labour of love," "as loving as it is laborious, maybe," is how the Guardian's Peter Bradshaw put it, writing (generally quite favorably) from Toronto. In her intro piece for the first part of the New York Film Festival for the Times Manohla Dargis linked it with the difficult Albert Serra'S Liberté with a one-word reaction: "oof," though she complemented these two as "choices rather than just opportunistically checked boxes." Motherless Brooklyn has many reasons for wanting to be in the New York Film Festival, and for the honor of Closing Night Film, notably the personal passion, but also the persistent rootedness in New York itself through these permutations.

Motherless Brooklyn, 144 mins., debuted at Telluride Aug. 30, 2019, showing at eight other festivals including Toronto, Vancouver, Mill Valley, and New York, where it was screened at the NYFF OCT. 11, 2019 as the Closing Night film. It opens theatrically in the US Nov. 1, 2019. Current Metascore 60%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 09-08-2021 at 02:08 PM.

-

THE IRISHMAN (Martin Scorsese 2019)

[Found also in Filmleaf's Festival Coverage section for the 2019 NYFF]

MARTIN SCORSESE: THE IRISHMAN (2019)

AL PACINO AND ROBERT DE NIRO IN THE IRISHMAN

Old song

From Martin Scorsese, who is in his late seventies, comes a major feature that is an old man's film. It's told by an old man, about old men, with old actors digitized (indifferently) to look like and play their younger selves as well. It's logical that The Irishman, about Teamsters loyalist and mob hit man Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), who became the bodyguard and then (as he tells it) the assassin of Union kingpin Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino) should have been chosen as Opening Night Film of the New York Film Festival. Scorsese is very New York, even if the film is set in Detroit. He is also a good friend of Film at Lincoln Center. And a great American director with an impressive body of work behind him.

To be honest, I am not a fan of Scorsese's feature films. I do not like them. They are unpleasant, humorless, laborious and cold. I admire his responsible passion for cinema and incestuous knowledge of it. I do like his documentaries. From Fran Lebowitz's talk about the one he made about her, I understand what a meticulous, obsessive craftsman he is in all his work. He also does have a sense of humor. See how he enjoys Fran's New York wit in Public Speaking. And there is much deadpan humor in The Irishman at the expense of the dimwitted, uncultured gangsters it depicts. Screenwriter Steven Zaillian's script based on Charles Brandt's book about Sheeran concocts numerous droll deadpan exchanges. It's a treat belatedly to see De Niro and Pacino acting together for the first time in extended scenes.

The Irishman is finely crafted and full of ideas and inspires many thoughts. But I found it monotonous and overlong - and frankly overrated. American film critics are loyal. Scorsese is an icon, and they feel obligated, I must assume, to worship it. He has made a big new film in his classic gangster vein, so it must be great. The Metascore, 94%, nonetheless is an astonishment. Review aggregating is not a science, but the makers of these scores seem to have tipped the scales. At least I hope more critics have found fault with The Irishman than that. They assign 80% ratings to some reviews that find serious fault, and supply only one negative one (Austin Chronicle, Richard Whittaker). Of course Armond White trashes the movie magnificently in National Review ("Déjà Vu Gangsterism"), but that's outside the mainstream mediocre media pale.

Other Scorsese stars join De Niro and Pacino, Joe Pesci, Harvey Keitel. This is a movie of old, ugly men. Even in meticulously staged crowd scenes, there is not one young or handsome face. Women are not a factor, not remotely featured as in Jonathan Demme's delightful Married to the Mob. There are two wives often seen, in the middle distance, made up and coiffed to the kitsch nines, in expensive pants suits, taking a cigarette break on car trips - it's a thing. But they don't come forward as characters. Note also that out of loyalty to his regulars, Scorsese uses an Italo-American actor to play an Irish-American. There's a far-fetched explanation of Frank's knowledge of Italian, but his Irishness doesn't emerge - just another indication of how monochromatic this movie is.

It's a movie though, ready to serve a loyal audience with ritual storytelling and violence, providing pleasures in its $140 million worth of production values in period feel, costumes, and snazzy old cars (though I still long for a period movie whose vehicles aren't all intact and shiny). This is not just a remake. Its very relentlessness in showing Frank's steady increments of slow progress up the second-tier Teamsters and mafia outsider functionary ladders is something new. But it reflects Scorsese's old worship of toughs and wise guys and seeming admiration for their violence.

I balk at Scorsese's representing union goons and gangsters as somehow heroic and tragic. Metacritic's only critic of the film, Richard Whittiker of the Austen Chronicle, seems alone in recognizing that this is not inevitable. He points out that while not "lionizing" mobsters, Scorsese still "romanticizes" them as "flawed yet still glamorous, undone by their own hubris." Whittiker - apparently alone in this - compares this indulgent touch with how the mafia is shown in "the Italian poliziotteschi," Italian Years of Lead gang films that showed them as "boors, bullies, and murderers, rather than genteel gentlemen who must occasionally get their hands dirty and do so oh-so-begrudgingly." Whittiker calls Scorsese's appeal to us to feel Sheeran's "angst" when he's being flown in to kill "his supposed friend" (Hoffa) "a demand too far."

All this reminded me of a richer 2019 New York Film Festival mafia experience, Marco Bellocchio's The Traitor/Il traditore, the epic, multi-continent story of Tommaso Buscetta, the first big Italian mafia figure who chose to turn state's witness. This is a gangster tale that has perspective, both morally and historically. And I was impressed that Pierfrancesco Favino, the star of the film, who gives a career-best performance as Buscetta, strongly urged us both before and after the NYFF public screening to bear in mind that these mafiosi are small, evil, stupid men. Coppola doesn't see that, but he made a glorious American gangster epic with range and perspective. In another format, so did David Chase om the 2000-2007 HBO epic, "The Sopranos." Scprsese has not done so. Monotonously, and at overblown length, he has once again depicted Italo-Americans as gangsters, and (this time) unions as gangs of thugs.

The Irishman, 209 mins,. debuted at New York as Opening Night Film; 15 other international festivals, US theatrical release Nov. 1, wide release in many countries online by Netflix Nov. 27. Metascore 94%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 11-23-2019 at 08:49 PM.

-

BACURAU (Kleber Mendonça Filho, Juliano Dornelles 2019)

KLEBER MENDOÇA FILHO, JULIANO DORNELLES: BACURAU (2019)

SONIA BRAGA (CENTER) IN BACURAU

Not just another Cannes mistake?

This is a bold film for an arthouse filmmaker to produce, and it has moments of rawness and unpredictability that are admirable. But it seems at first hand to be possibly a misstep both for the previously much subtler chronicler of social and political unease as seen in the 2011 Neighboring Sopunds and 2016 Aquarius, Kleber Mendonça Filho, and for Cannes, which may have awarded novelty rather than mastery in giving it half of the 2019 Jury Prize. It's a movie that excites and then delivers a series of scenes of growing disappointment and repugnance. But I'm not saying it won't surprise and awe you.

Let's begin with where we are, which is the Brazilian boonies. Bacurau was filmed in the village of Barra in the municipality of Parelhas and in the rural area of the municipality of Acari, at the Sertão do Seridó region, in Rio Grande do Norte. Mendonça Filho shares credit this time with his regular production designer Juliano Dornelles. (They both came originally from this general region, is one reason.) The Wikipedia article introduces it as a "Brazilian weird western film" and its rural shootout, its rush of horses, its showdowns, and its truckload of coffins may indeed befit that peculiar genre.

How are we to take the action? In his Hollywood Reporter review, Stephen Dalton surprises me by asserting that this third narrative feature "strikes a lighter tone" than the first two and combines "sunny small-town comedy with a fable-like plot" along with "a sprinkle of magic realism." This seems an absurdly watered down description, but the film is many things to many people because it embodies many things. In an interview with Emily Buder, Mendoça Filho himself describes it as a mix of "spaghetti Western, '70's sci-fi, social realist drama, and political satire."

The film feels real enough to be horrifying, but it enters risky sci-fi horror territory with its futuristic human hunting game topic, which has been mostly an area for schlock. (See a list of ten, with the 1932 Most Dangerous Game given as the trailblazer.) However, we have to acknowledge that Mendonca Filho is smart enough to know all this and may want to use the schlock format for his own sophisticated purpose. But despite Mike D'Angelo's conclusion on Letterboxd that the film may "require a second viewing following extensive reading" due to its rootedness in Brazilian politics, the focus on American imperialists and brutal outside exploiters from the extreme right isn't all that hard to grasp.

Bacurau starts off as if it means to be an entertainment, with conventional opening credits and a pleasant pop song celebrating Brazil, but that is surely ironic. A big water truck rides in rough, arriving with three bullet holes spewing agua that its driver hasn't noticed. (The road was bumpy.) There is a stupid, corrupt politician, mayor Tony Jr. (Thardelly Lima), who is complicit in robbing local areas of their water supply and who gets a final comeuppance. The focus is on Bacurau, a little semi-abandoned town in the north whose 94-year-old matriarch Carmelita dies and gets a funeral observation in which the whole town participates, though apart the ceremony's strange magic realist aspects Sonia Braga, as a local doctor called Domingas, stages a loud scene because she insists that the deceased woman was evil. Then, with some, including Carmelita's granddaughter Teresa (Barbara Colen), returned to town from elsewhere, along with the handsome Pacote (Tomaso Aquinas) and a useful psychotic local killer and protector of water rights called Lunga (Silvero Pereira), hostile outsiders arrive, though as yet unseen. Their forerunners are a colorfully costumed Brazilian couple in clownish spandex suits on dustrider motorcycles who come through the town. When they're gone, it's discovered seven people have been shot.

They were an advance crew for a gang of mostly American white people headed by Michael (Udo Kier), whose awkward, combative, and finally murderous conference we visit. This is a bad scene in more ways than one: it's not only sinister and racist, but clumsy, destroying the air of menace and unpredictability maintained in the depiction of Bacurau scenes. But we learn the cell phone coverage of the town has been blocked, it is somehow not included on maps, and communications between northern and southern Brazil are temporarily suspended, so the setting is perfect for this ugly group to do what they've come for, kill locals for sport using collectible automatic weapons. Overhead there is a flying-saucer-shaped drone rumbling in English. How it functions isn't quite clear, but symbolically it refers to American manipulation from higher up. The way the rural area is being choked off requires no mention of Brazil's new right wing strong man Jair Bolsonaro and the Amazonian rain forest.

"They're not going to kill a kid," I said as a group of local children gather, the most normal, best dressed Bacurauans on screen so far, and play a game of dare as night falls to tease us, one by one creeping as far as they can into the dark. But sure enough, a kid gets shot. At least even the bad guys agree this was foul play. And the bad guys get theirs, just as in a good Western. But after a while, the action seems almost too symbolically satisfying - though this is achieved with good staging and classic visual flair through zooms, split diopter effects, Cinemascope, and other old fashioned techniques.

I'm not the only one finding Bacurau intriguing yet fearing that it winds up being confused and all over the place. It would work much better if it were dramatically tighter. Peter DeBruge in Variety notes that the filmakers "haven’t figured out how to create that hair-bristling anticipation of imminent violence that comes so naturally to someone like Quentin Tarantino." Mere vague unexpectedness isn't scary, and all the danger and killing aren't wielded as effectively as they should be to hold our attention and manipulate our emotions.

Bacurau, 131 mins., debuted in Competition at Cannes, where it tied for the Jury Prize with the French film, Ladj Ly's Les misérables. Many other awards and at least 31 other festivals including the NYFF. Metascore 74%. AlloCiné press rating 3.8, with a rare rave from Cahiers du Cinéma. US theatrical distribution by Kino Lorber began Mar. 13, 2020, but due to general theater closings caused by the coronavirus pandemic the company launched a "virtual theatrical exhibition initiative," Kino Marquee, with this film from Mar. 19.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-05-2020 at 01:24 PM.

-

ZOMBI CHILD (Bertrand Bonello 2019)

BERTRAND BONELLO: ZOMBI CHILD (2019)

LOUISE LABEQUE AND WISLANDA LOUIMAT (FAR RIGHT) IN ZOMBI CHILD

Voodoo comes to Paris

If you said Betrand Bonello's films are beautiful, sexy, and provocative you would not be wrong. This new, officially fifth feature (I've still not seen his first one, the 2008 On War), has those elements. Its imagery, full of deep contrasts, can only be described as lush. Its intertwined narrative is puzzling as well.

We're taken right away to Haiti and plunged into the world of voodoo and zombies. Ground powder from the cut-up body of a blowfish is dropped, unbeknownst to him, into a man's shoes. Walking in them, he soon falters and falls. Later, he's aroused from death to the half-alive state of a zombie - and pushed into a numb, helpless labor in the hell of a a sugar cane field with other victims of the same cruel enchantment. In time however something arouses him to enough life to escape.

Some of the Haitian sequences center around a moonlit cemetery whose large tombs seem airy and haunted and astonishingly grand for what we know as the poorest country in the hemisphere.

From the thumping, vibrant ceremonies of Haitian voodoo (Bonello's command of music is always fresh and astonishing as his images are lush and beautiful) we're rushed to the grandest private boarding school you've ever seen, housed in vast stone government buildings. This noble domaine was established by Napoleon Bonaparte on the edge of Paris, in Saint Denis, for the education of children of recipients of the Legion of Honor. It really exists, and attendance there is still on an honorary basis.

Zombi Child oscillates between girls in this very posh Parisian school and people in Haiti. But these are not wholly separate places. A story about a Haitian grandfather (the zombie victim, granted a second life) and his descendants links the two strains. It turns out one of those descendants, Mélissa (Wislanda Louimat), is a new student at the school. A white schoolgirl, Fanny (the dreamy Louise Labeque), who's Mélissa's friend and sponsors her for membership in a sorority, while increasingly possessed by a perhaps imaginary love, also bridges the gap. For the sorority admission Mélissa confesses the family secret of a zombi and voodoo knowledge in her background.

Thierry Méranger of Cahiers du Cinéma calls this screenplay "eminently Bonellian in its double orientation," its "interplay of echoes" between "radically different" worlds designed to "stimulate the spectator's reflection." Justin Chang of the Los Angeles Times bluntly declares that it's meant to "interrogate the bitter legacy of French colonialism."

But how so? And if so, this could be a tricky proposition. On NPR Andrew Lapin was partly admiring of how "cerebral and slippery" the film is, but suggests that since voodoo and zombies are all most white people "already know" about Haitian culture, a director coming from Haiti's former colonizing nation (France) must do "a lot of legwork to use these elements successfully in a "fable" where "the real horror is colonialism." The posh school comes from Napoleon, who coopted the French revolution, and class scenes include a history professor lecturing on this and how "liberalism obscures liberty."

I'm more inclined to agree with Glenn Kenny's more delicately worded praise in his short New York Times review of the film where he asserts that the movie’s inconclusiveness is the source of its appeal. Zombi Child, he says, is fueled by insinuation and fascination. The fascination, the potent power, of the occult, that's what Haiti has that the first wold lacks.

One moment made me authentically jump, but Bonello isn't offering a conventional horror movie. He's more interested in making his hints of voodoo's power and attraction, even for the white lovelorn schoolgirl, seem as convincing as his voodoo ceremonies, both abroad and back in Haiti, feel thoroughly attractive, or scary, and real. These are some of the best voodoo scenes in a movie. This still may seem like a concoction to you. Its enchantments were more those of the luxuriant imagery, the flowing camerawork, the delicious use of moon- and candle-light, the beautiful people, of whatever color. This is world-class filmmaking even if it's not Bonello's best work.

Bonello stages things, gets his actors to live them completely, then steps back and lets it happen. Glenn Kenny says his "hallmark" is his "dreamy detachment." My first look at that was the 2011 House of Tolerence (L'Apollonide - mémoires de la maison close), which I saw in Paris, a languorous immersion in a turn-of-the-century Parisian brothel, intoxicating, sexy, slightly repugnant. Next came his most ambitious project, Saint Laurent(2014), focused on a very druggy period in the designer's career and a final moment of decline. He has said this became a kind of matching panel for Apollonide. (You'll find that in an excellent long Q&A after the NYFF screening.) Saint Laurent's "forbidden" (unsanctioned) picture of the fashion house is as intoxicating, vibrant, and cloying as the maison close, with its opium, champagne, disfigurement and syphilis. No one can say Gaspard Ulliel wasn't totally immersed in his performance. Nocturama (2016) takes a group of wild young people who stage a terrorist act in Paris, who seem to run aground in a posh department store at the end, Bonello again getting intense action going and then seeming to leave it to its own devices, foundering. Those who saw the result as "shallow cynicism" (like A.O. Scott) missed how exciting and powerful it was. (Mike D'Angelo didn't.)

Zombi Child is exciting at times too. But despite its gorgeous imagery and sound, its back and forth dialectic seems more artificial and calculating than Bonello's previous films.

Zombi Child, mins., debuted at Cannes Directors Fortnight May 2019, included in 13 other international festivals, including Toronto and New York. It released theatrically in France Jun. 12, 2020 (AlloCiné press rating 3.7m 75%) and in the US Jan. 24, 2020 (Metascore 75%). Now available in "virtual theater" through Film Movement (Mar. 23-May 1, 2020), which benefits the theater of your choice. https://www.filmmovement.com/zombi-child

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-07-2025 at 11:46 PM.

-

WASP NETWORK (Olivier Assayas 2019)

OLIVIER ASSAYAS: WASP NETWORK (2019)

GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL AND PENELOPE CRUZ IN WASP NETWORK

Spies nearby

The is a movie about the Cuban spies sent to Miami to combat anti-Castro Cuban-American groups, and their capture. They are part of what the Cubans called La Red Avispa (The Wasp Network). The screenplay is based on the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War by Fernando Morais, and it's mainly from the Wasp, Cuban point of view, not the FBI point of view. Unlike the disastrous Seberg, no time is spent looking over the shoulders of G-men, nor will this story give any pleasure to right wing Miami Cubans. But it won't delight leftists much either, or champions of the Cuban Five. The issues of why one might leave Cuba and why one might choose not to are treated only superficially. There's no analysis of US behavior toward Cuba since the revolution.

On the plus side, the film is made in an impeccable, clear style (with one big qualification: see below) and there's an excellent cast with as leads Edgar Ramirez (of the director's riveting miniseries Carlos), Penelope Cruz (Almodóvar's muse), Walter Moura (Escobar in the Netflix series "Narcos"), Ana de Armas (an up-and-comer who's actually Cuban but lives in Hollywood now), and Gael García Bernal (he of course is Mexican, Moura is Brazilian originally, and Ramirez is Venezuelan). They're all terrific, and other cast members shine. Even a baby is so amazing I thought she must be the actress' real baby.

Nothing really makes sense for the first hour. We don't get the whole picture, and we never do, really. We focus on René Gonzalez (Édgar Ramirez), a Puerto Rican-born pilot living in Castro’s Cuba and fed up with it, or the brutal embargo against Castro by the US and resulting shortage of essential goods and services, who suddenly steals a little plane and flies it to Miami, leaving behind his wife Olga and young daughter. Olga is deeply shocked and disappointed to learn her husband is a traitor. He has left without a word to her. Born in Chicago, he was already a US citizen and adapts easily, celebrated as an anti-Castro figure.

We also follow another guy, Juan Pablo Roque (Wagner Moura) who escapes Havana by donning snorkel gear and swimming to Guantanamo, not only a physical challenge but riskier because prison guards almost shoot him dead when he comes out of the water. Roque and Gonzalez are a big contrast. René is modest, content with small earnings, and starts flying for a group that rescues Cuban defectors arriving by water. Juan Pablo immediately woos and marries the beautiful Ana Marguerita Martinez (Ana de Armas) and, as revealed by an $8,000 Rolex, is earning big bucks but won't tell Ana how. This was the first time I'd seen Wagner Moura, an impressively sly actor who as Glenn Kenny says, "can shift from boyish to sinister in the space of a single frame" - and that's not the half of it.

This is interesting enough to keep us occupied but it's not till an hour into the movie, with a flashback to four years earlier focused on Cuban Gerardo Hernandez (Garcia Bernal) that we start to understand something of what is going on. We learn about the CANF and Luis Posada Carriles (Tony Plana), and a young man's single-handed effort to plant enough bombs to undermine the entire Cuban tourist business. This late-arriving exposition for me had a deflating and confounding effect. There were still many good scenes to follow. Unfortunately despite them, and the good acting, there is so much exposition it's hard to get close to any of the individual characters or relationships.

At the moment I'm an enthusiastic follower of the FX series "The Americans." It teaches us that in matters of espionage, it's good to have a firm notion of where the main characters - in that case "Phillip" and "Elizabeth" - place their real, virtually unshakable loyalties, before moving on. Another example of which I'm a longtime fan is the spy novels of John le Carré. You may not be sure who's loyal, but you always know who's working for British Intelligence, even in the latest novel the remarkable le Carré, who at 88, has just produced (Agent Running in the Field - for which he's performed the audio version, and no one does that better). To be too long unclear about these basics in spydom is fatal.

It's said that Assayas had a lot of trouble making Wasp Network, which has scenes shot in Cuba in it. At least the effort doesn't show. We get a glimpse of Clinton (this happened when he was President) and Fidel, who, in a hushed voice, emphatically, asserts his confidence that the Red Avispa was doing the right thing and that the Americans should see that. Whose side do you take?

Wasp Network, 123 mins., debuted at Venice and showed at about ten other international festivals including Toronto, New York, London and Rio. It was released on Netflix Jun. 19, 2019, and that applies to many countries (13 listed on IMDb). Metascore 54%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 07-31-2025 at 03:14 PM.

-

THE PRESIDENT'S CAKE (Hasan Hadi 2025)

HASAN HADI: THE PRESIDENT'S CAKE (2025)

Childhood in Iraq in the age of Saddam

It might be churlish not to admire Hasan Hadi's passion project first feature, which (in the wake of today's opening in Paris of The Children of the Resistance) seems a bit like a volume from a series of graphic novels, "Children of Saddam Hussein." Set in the early nineties, the film follows a nine-year-old girl and boy who go on a useless errand to fulfil a forced "patriotic" project. Their martinet of a schoolteacher (he wields far more stick than carrot) has held a drawing. The dear leader's birthday is coming. The teacher pretends these tasks are rewards, but the way he forces a boy who arrives late by entering his name in the box five times shows it is a punishment. There will be more punishment for any of the "lucky ones" who don't come up with the assigned offering. And all this is a charade. The stuff will just be presented in class, not sent to the presidential palace.

With very gentle irony, the film ends with a brief clip of the actual celebration, his 50th. Those chosen in the class are assigned projects to celebrate this "great" event. Sa3id is to gather fresh fruit. Lam3iyya has a tougher task: to bake a cake. Eggs, flour and baking powder happen to be in very short supply. The meanness of the class situation has been shown by how the teacher has stolen Lam3iyya's lunch, an apple, from her briefcase. She is the top student in the class. What is her reward for that?

If the makings of cake are hard to come bay, so is money. This is the early 1990's. The US-led "Persian Gulf War" is going on. The film depicts the harsh conditions following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait and the subsequent international sanctions, focusing on the impact of this wartime, impoverished environment on daily life.

But this plays out in a combination of Italian neorealism and a fairy tale - or the graphic novel referred to above. Only instead of a lost bike, the two kids, who go around together, along with a rooster, are looking for goods that are almost impossible to get for a useless ceremonial purpose. The title, Kingdom of the Marshes, is pointed because while not otherwise essential to the story, it refers to a region Saddam Hussein had filled in, destroying a way of life, in revenge against a group that was insufficiently obedient to him. The dp presents a lovely pastoral scene of marshland life in the film's opening. Obviously some of it remains because we see the characteristic buildings made of reeds as well as the boats.

Hadi is terrific both in his recreation of the setting - an impoverished world dominated by huge portraits of the dictator - and in his use of young non-actors, especially Baneen Ahmed Nayyef as the girl and Sajad Mohamad Qasem as the boy, not to mention, as the girl's grandmother "Bibi," Waheeda Thabet, a venerable, leathery-faced crone you don't want to mess with. This is an ironic work. It doesn't have the tragic resonance of Georges Poujouly and Brigitte Fossey in René Clément's shatteringly sad 1952 Forbidden Games set in WWII France.

Though it could be moving into [I]Forbidden Games[/I territory in its final classroom scene, mostly what Cake has is the determination of long sufferers. The devil is in the details of this film as mostly Lam3iyya's quest is followed. She even tries to trade jewelry or a camera to pay for the treasured ingredients. The exhausting quest really does parallel De Sica's Ladri di biciclette in narrative structure.

We learn a little about the kids. Sa3id's father is a beggar and he is trained himself as a little thief. But as emerges in an argument, at least he has a father; Lam3iyya doesn't. She has the indestructible Bibi, who, in the end, under all this pressure, isn't. It is Sa3id's mother who bakes the cake.

They encounter a pregnant woman who is so grateful to the kids she promises to name her baby after them. But when she learns the girl's name is Lam3iyya, she strongly hopes it is a boy. This is just personal preference - and another little joke.

Shri Linden in a Cannes Hollywood Reporter review found "lovely comedy" in the way Sa3id and Lam3iyya "bicker like a long-married couple," felt with them the "anguished pangs" when "their tensions explode" in a "memorable" rooftop scene, and described the film as "a tragicomic gem."

What we can admire most is the way the gone era of Iraqi life is lovingly - if with half shielded eyes against its depredations. Hadi's gift is evident, though next time we may hope he relies less on styles of the past.

The President's Cake/ مملكة القصب (mamlikat al-qassab "Kingdom of Reeds", 105 mins., premiered in Cannes Directors' Fortnight May 16, 2025, playing in dozens of other festivals including Hamptons, BFI, Mill Valley, Athens, Chicago. Limited US theatrical release beginning Feb. 6, 2026. Metacritic rating: 88%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; Yesterday at 05:56 PM.

-

ELIE WIESEL: SOUL ON FIRE (Oren Rudavsky 2024)

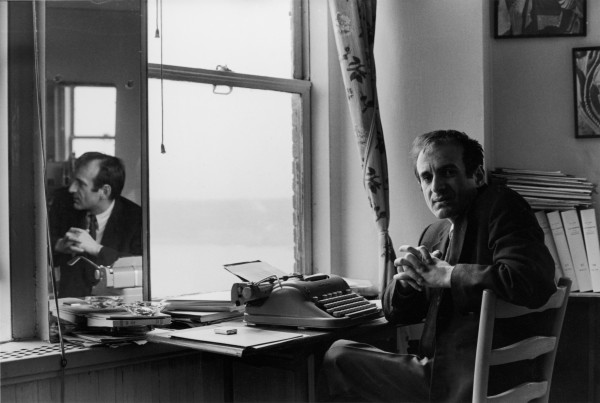

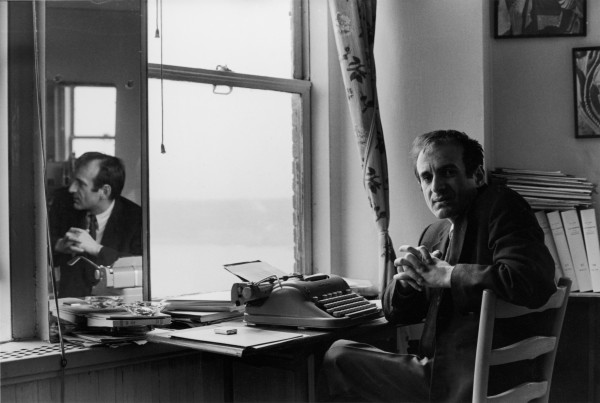

AN ARCHIVAL PHOTO SHOWN IN ELIE WIESEL: SOUL ON FIRE

OREN RUDAVSKY: ELIE WIESEL: SOUL ON FIRE (2024)

Holocaust "storyteller" gets more a tribute than an analysis

Ruavsky's short film is part of the US television "American Masters" series. But was Elie Wiesel, its' subject, an "American master"? Rather, a wartime survivor from a shtetl in Romania, he was a spokesman of remembrance, for both the US and the world, of the Nazi effort to eradicate the Jews in World War II, a murderous effort that came to be known as "the Holocaust." That role sometimes made him seem strident or exploitive. But overall, perhaps he was a force for good, insofar as the new generations preserve any knowledge of the previous century. Perhaps we should not expect much of an "American Masters" episode. But as a portrait this film, though well made feels, insufficiently rounded and penetrating.

Its finest moments may be its use of flickering black and white animation early on as a way to depict the greatest horrors of Nazi oppression as a way to poetically express the inexpressible.

Wiesel's parents and one sibling died at the hands of the Nazis. He and his sister survived Auschwitz and Buchenwald as teenagers. When the camp was liberated in 1945, a group photograph was taken. It features emaciated inmates including Wiesel, a gaunt, angular and spectral young man but a lucky survivor. He and his sister were sent to a French orphanage and they were later reunited. He acquired a distinguished education in Paris and became a friend of François Mauriac and other French intellectuals. Some of his testimony here is in French, in footage whose provenance we don't know. What becomes clear is that he decided to make describing the suffering of the Jews in the War the focus of his life: to be a professional, full-time witness to the Holocaust.

From a social media discussion of Wiesel on Instagram initiated by awarded-winning Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha, quoting from an eloquent statement by Wiesel he cites somewhat ironically as concerning Gaza. A contributor, identified as Ruby Moonshine, wrote, "He was my professor for a class at BU. He was a brilliant literary thinker, an interesting writer, a Jewish scholar and he was not a very nice man. Misogynist and impatient and a Zionist in every way, shape and form. He did not give a care about Palestinians at all. I learned in his class that the prophet has clay feet."

Wikipedia: "Wiesel also played a role in the initial success of The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosinski by endorsing it before it became known the book was fiction and, in the sense that it was presented as all Kosinski's true experience, a hoax."

The Guardian in 2000 recounted an encounter between Norman Finkelstein and Elie Wiesel. The article headlines with (about Finkelstein), "His accusation that Zionist groups profit from hijacking the history of the Nazi genocide has made him a hate figure." But Finkelstein has been proven right. Finkelstein has written about the "Holocaust industry." He has asserted, in the Guardian piece's words, that "Wiesel is a hypocrite, responsible for the 'sacralization of the Holocaust ... for his standard fee of $25,000 (plus chauffeured limousine)', transforming it into an ideological tool used to shield Israel from criticism and serve the interests of the U.S. and Israel. Finkelstein refers to Wiesel as the "resident clown of the Holocaust circus" and stated that the term "Shoah-business" (Shoah being Hebrew for "holocaust") was "literally coined for such qualifications, being himself the son of concentration camp survivors.

But Finkelstein, a strong critic of Elie Wiesel, is not heard from in this film.

Finkelstein has held in his book The Holocaust Industry and elsewhere, that Holocaust survivors and their descendants could be used by the all-powerful American Jewish lobby to lend a kind of moral victimhood to an Israeli state engaged in criminal acts against the Palestinians. Over the intervening years, this has emerged as a self-evident truth, and the actions of the State of Israel are less and less possible to justify. Most recently, international bodies have judged the actions of Israel in Gaza to qualify as genocide. And all along the Holocaust has been used to justify anything. Back in his day Elie Wiesel spearheaded this kind of propaganda and was skillful in wielding it. But none of this is in Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire.

Wikipedia: "Wiesel was critical of Hamas; he condemned them for the 'use of children as human shields' during the 2014 Gaza War, and ran an ad in several large newspapers to express this message. The New York Times refused to run the advertisement, saying, 'The opinion being expressed is too strong, and too forcefully made, and will cause concern amongst a significant number of Times readers.'" It is telling indeed that the Times, which has been such a warm supporter of Israel, should find Wiesel's claims a step too far. The claim that Palestinians have used any people as "human shields" has been a longtime favorite of anti-Palestinian propaganda.

Wiesel's first and most famous book, Night is described, but only externally. We are told it was originally 800 pages in Yiddish, then greatly pared down and published in French (as La nuit); for a long time ignored, then gradually famous and an international bestseller. Of Wiesel's additional 56 books, details are lacking.

A voice in this film says when he asked Wiesel what he did, he replied that he was a "storyteller." He said this when - in an incident covered in detail in this film - Wiesel spoke up to President Reagan after being awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, and begged Reagan not to visit a cemetery in Bitburg, Germany. The film shows Wiesel receiving the Nobel Peace Prize the very next year, he brought his 14-year-old son Elisha up to the podium with him. The adult Elisha explains that, living as he did so much already in the shadow of his father, this was exactly what he did not want to have happen at the time.

An hour or so in, this film, which has shown Wiesel's white-haired widow frequently as a talking head, and now his grown son, begins to focus on his descendants, a vibrant family that has become devoutly Jewish. But seeing the family hanging out and celebrating Passover adds little to the portrait of Elie. Complex issues raised by the life don't get a chance for the detailed exploration they need.

The widow for one brief moment plainly states that her husband would never accept criticism of Israel or the behavior of the Jewish settlers on Palestinian lands, but this is only a moment. He went from being a witness to being a propagandist. He got to speak presidents in nationally broadcast moments, he got to receive a Nobel Prize, he got to receive that ultimate honor, to go on "Oprah." But he didn't come to terms with what Israel became. This little film, for all its rich photographic documents and its many archival and current film clips in English, French, Hebrew, and Yiddish, is at best more a eulogy than a rounded critical portrait.

Nonetheless, the final moments oft he film are very beautiful.

Elie Wiesel: Soul on Fire, 87 mins., premiered at the Hamptons Oct. 5, 2024. It showed Aug. 29, 2025 at Telluride. Its limited release in the US was on Sept. 16, 2025 at IFC Center, NYC via Panorama Films. It opened at the Siskel Film Center in Chicago on Jan. 9, 2026. It screens in the Bay Area Jan. 27, 2026.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 01-24-2026 at 01:13 AM.

-

AT WORK/A PIED DE L'OEUVRE (Valerie Donzelli 2025) - R-V

BASTIEN BOUILLON IN AT WORK

VALERIE DONZELLI: AT WORK/À PIED DE L'OEUVRE (2025)

Oath of poverty of an author doing Uber-style work

THe French review Les Inrockuptibles of Valerie Donzelli's quietly powerful and succinct new film, describes the hero, Paul (Bastien Bouillon) thus: "a rebellious, unconventional artist who chooses fulfillment in poverty and marginality rather than compromise in the limelight." Some French reviewers see the subject of At Work negatively, as a tale of of "uberisation." Surely is not so. Uber is just a thing people do on the way to something else. But Uber reflects a fracturing of work that was simpler before. In the words of the author of the source novel, which is a realistic, experienced-based account, it is "a clever blend of liberty and deprivation." To put it another way, Paul, an established, published writer but not a hugely successful one, allows himself to be exploited for the little things to avoid the big exploitation of a profitable but shameful and dishonest job, like, say, finance or advertising, or even teaching, which is too close to the intellectual activity of writing. Menial work puts the writer in direct touch with life at its most ordinary and keeps him honest.

Paul (Bastien Bouillon, who is brilliant here, and makes the film), is in his early forties, recently divorced with several grown children, whom circumstances lead to be living by himself now; the wife takes the kids to live in Canada. He was a successful photographer, making two or three thousand euros a month. He looks at his cameras, relics now. He will not go back to photography to make money. He has published three novels and is embarking on his fourth.

Though unnoted, the publisher is NRF/Gallimard, publisher of such luminaries as Proust, Sartre, St. Exupéry, Céline and De Beauvoir. Paul is not one of those. His number three did poorly as his editor (Viginie Ledoyen) reminds him. He is making 250 euros a month where before, as a photographer, he made two or three thousand. But Paul wants to write, so he must do other work to live. But not photography, which was another life.

The film is about the work he chooses to do, and about his dedication to the métier of writer. Occasionally we see his editor, and moderately but also essentially we glimpse his wife, played by Donzelli herself. He chooses to work at menial jobs to leave himself time and mind to write and the film focuses much on these jobs. Why not write a bestseller?, his disapproving father (André Marcon) asks. He would not consider it. The jobs are ordinary but sometimes grueling, piecework, miscellaneous gig economy jobs. He takes three hours to cut a lawn because the owner has only clippers. He struggles unloading a metal curved staircase down a stairway out of an apartment for too heavy ahd too cumbersome for one person. He spends ages laboriously removing big boxwood plants (we may pity the plants themselves too) from large planters on a Paris balcony, only to learn that there is another side to the balcony with another eight boxwoods to drag out and bag.

He takes a gold ring to sell, and finds out it's not 18 carat gold. He lets it go anyway, for thirty euros.

Paul is so swamped, and so poor now, he can't afford trips for festive events involving his children who are out of town, and must attend them via Zoom. His hair has been cropped close with clippers: he's like a monk. A friend he dines with says "tu décelaire," you're slowing down, but it sounded to me like "tu désalaire" - you're giving up salary. It's both. Slowly, quietly, invisibly, Paul makes his life workable, earning enough to live on minimally by odd jobs, while continuing to write, and keeping not of all the people and scenes he observes on his jobs.

He is an Uber to and from the airport. One is a lonely lady he goes to bed with on arrival. But they are both out of practice and it's awkward and dodgy. He must give up the loaned space he's moved to and is faced with homelessness, becoming a 'clochard.' His computer gives out and something goes so wrong not only can it not be repaired, but he loses his drive and all his work on it. A lady barkeep has pity on him and leads him to a rest space behind the bar and says he can stay there and write there. He takes to felt pen and pad.

The whole business, the family, the publisher, the odd jobs he does for a pittance to get them from the hot online competition, life day to day, go into the packet of pages he produces and gives to his editor. She directs it to be typed up and bound and when we see that, we know good news has come at last. She finds the book good, it will be his next book.

At the signing, he gets a text about a job, a referral from a previous client. "In two hours?" he texts -- he will go from the book signing to another repair job, because the editor, having paid him an advance some time ago, cannot give him any more when she takes his manuscript. But the buyers of the book are loyal. "I like your writing. I've read all your books." That, at least, is real gold. But better than that,platinum perhaps, is the enormously moving call from his own son, who has read the book (which his children had not done the early ones) and loves it and in whose eyes he has become a mensch.

As an Uber worker Paul points out in the book, he has to be constantly rated, and he is only hirable if he gets five stars. A customer writes he is too untalkative and gives him one star, and his rating drops. Employers no longer fear employees. It's a tough world out there. What happened to Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité?

In the neat final scene of this neat little film, the client after the book signing thanks Paul for his toilet repair, gives him the 25 euros, and says, "My friend is moving tomorrow morning. Can I recommend you to her?" and Paul says, "Yes. But I don't work mornings. Mornings I write." End of story.

(À pied d'œuvre, the title, means in English " » signifie en anglais « to be ready to start work," "to be on site and ready," in or "to be hard at work" in the context of a team project or construction site.)

At Work/À pied d'oeuvre, 92 mins., premiered in competition at Venice Aug. 29, 2025, showing also at Hamburg, Marrakech and Göteborg, and opened Feb, 4 in France and will open Mar. 5 in Italy. AlloCiné press rating 3.9 (78%). Screened for this review as part of the Mar. 5-15, 2026 Rendez-Vous with French Cinema at Lincoln Center. Showtimes:

Sunday, March 8 at 9:00pm – Q&A with Valérie Donzelli

Friday, March 13 at 4:00pm

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-08-2026 at 11:10 PM.

-

WRITING LIFE: ANNIE ERNAUX THROUGH THE EYES OF HIGHSCHOOL STUDENTS (Claire Simon 20

CLAIRE SIMON: WRITING LIFE: ANNIE ERNAUX THROUGH THE EYES OF HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS (2025)

Claire Simon’s documentary, Writing Life: Annie Ernaux Through The Eyes Of High School Students, studies literary engagement with a calm, inviting gaze. The film centers on Nobel Laureate Annie Ernaux’s work. Simon watches French teenagers read and discuss the author’s autobiographical texts in high school classrooms.

Ernaux’s prose has a direct, unadorned “flat” style that recounts personal experiences tied to social class, abortion, relationships, and family history. Simon mirrors that clarity through an observational approach that keeps the frame open and the tone steady. Sessions unfold across varied educational settings, from mainland France to Cayenne in French Guiana. The result is a quiet reflection on reading,...

Writing Life: Annie Ernaux Through the Eyes of High School Students / Écrire la vie - Annie Ernaux racontée par des lycéennes et des lycéens, 90 mins., comes Apr. 8, 2026 to French theaters.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-08-2026 at 11:11 PM.

-

METEORS (Hubert Charuel, Claude Le Pape 2025)

HUBERT CHARUEL, CLAUDE LE PAPE: METEORS (2025)

Jessica Kiang review Variety

Debuting at Cannes last May, Meteors focuses on three young "losers" in rural France (

Mika (Paul Kircher), Dan (Idir Azougli) and Tony (Salif Cissé), and follows to see who will succeed and who will fail. The actors are excellent; the story is depressing. The setting is what is called in the film the "upper Marne," and explained by Jessica Kiang in her review as " the sparsely populated swath of France that extends southwest from the borders of Belgium and Luxembourg to the Pyrenees: the 'diagonale du vide' or 'empty diagonal'."

An Allocine viewer's comment says it "mixes genres, buddy comedy, social drama, thriller, and melodrama, and creates a seemingly personal film about male friendship and dependence," but it almost seems to me most of all a horror film.

Meteors/Météors, Debuted May 2025 at Un Certain Regard in the Cannes Festival. It was screened for this review as part of the Rendez-Vous with FrenchCinema at Lincoln Center (Mar. 5-15, 2026).

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-09-2026 at 01:59 AM.

-

AT WORK (Valéri Donzelli 2025)

VALÉRIE DONZELLI: AT WORK/À PIED DE L'OEUVRE (2025)

Oath of poverty of an author doing gig economy work

THe French review Les Inrockuptibles of Valerie Donzelli's quietly powerful and succinct new film, describes the hero, Paul (Bastien Bouillon) thus: "a rebellious, unconventional artist who chooses fulfillment in poverty and marginality rather than compromise in the limelight." Some French reviewers see the subject of At Work negatively, as a tale of of "uberisation." Surely is not so. Uber is just a thing people do on the way to something else. But Uber reflects a fracturing of work that was simpler before. In the words of the author of the source novel, which is a realistic, experienced-based account, it is "a clever blend of liberty and deprivation." To put it another way, Paul, an established, published writer but not a hugely successful one, allows himself to be exploited for the little things to avoid the big exploitation of a profitable but shameful and dishonest job, like, say, finance or advertising, or even teaching, which is too close to the intellectual activity of writing. Menial work puts the writer in direct touch with life at its most ordinary and keeps him honest.

Paul (Bastien Bouillon, who is brilliant here, and makes the film), is in his early forties, recently divorced with several grown children, whom circumstances lead to be living by himself now; the wife takes the kids to live in Canada. He was a successful photographer, making two or three thousand euros a month. He looks at his cameras, relics now. He will not go back to photography to make money. He has published three novels and is embarking on his fourth.

Though unnoted, the publisher is NRF/Gallimard, publisher of such luminaries as Proust, Sartre, St. Exupéry, Céline and De Beauvoir. Paul is not one of those. His number three did poorly as his editor (Viginie Ledoyen) reminds him. He is making 250 euros a month where before, as a photographer, he made two or three thousand. But Paul wants to write, so he must do other work to live. But not photography, which was another life.

The film is about the work he chooses to do, and about his dedication to the métier of writer. Occasionally we see his editor, and more rarely but also essentially we glimpse his wife, played by Donzelli herself. He chooses to work at menial jobs to leave himself time and mind to write and the film focuses much on these jobs. Why not write a bestseller?, his disapproving father (André Marcon) asks. He would not consider it. The jobs are ordinary but sometimes grueling, piecework, miscellaneous gig economy jobs. He takes three hours to cut a lawn because the owner has only clippers. He struggles unloading a metal curved staircase down a stairway out of an apartment for too heavy ahd too cumbersome for one person. He spends ages laboriously removing big boxwood plants (we may pity the plants themselves too) from large planters on a Paris balcony, only to learn that there is another side to the balcony with another eight boxwoods to drag out and bag.

He takes a gold ring to sell, and finds out it's not good real gold. He lets it go anyway, for thirty euros.

Paul is so swamped, and so poor now, he can't afford trips for festive events involving his children who are out of town, and must attend them via Zoom. His hair has been cropped close with clippers: he's like a monk. A friend he dines with says "tu décelaire," you're slowing down, but it sounded to me like "tu désalaire" - you're giving up salary. It's both. Slowly, quietly, invisibly, Paul makes his life workable, earning enough to live on minimally by odd jobs, while continuing to write, and keeping not of all the people and scenes he observes on his jobs.

He is an Uber to and from the airport. One is a lonely lady he goes to bed with on arrival. But they are both out of practice and it's awkward and dodgy. He must give up the loaned space he's moved to and is faced with homelessness, becoming a 'clochard.' His computer gives out and something goes so wrong not only can it not be repaired, but he loses his drive and all his work on it. A lady barkeep has pity on him and leads him to a rest space behind the bar and says he can stay there and write there. He takes to felt pen and pad.

The whole business, the family, the publisher, the odd jobs he does for a pittance to get them from the hot online competition, life day to day, go into the packet of pages he produces and gives to his editor. She directs it to be typed up and bound and when we see that, we know good news has come at last. She finds the book good, it will be his next book.

At the signing, he gets a text about a job, a referral from a previous client. "In two hours?" he texts -- he will go from the book signing to another repair job, because the editor, having paid him an advance some time ago, cannot give him any more when she takes his manuscript. But the buyers of the book are loyal. "I like your writing. I've read all your books." That, at least, is real gold. But better than that,platinum perhaps, is the enormously moving call from his own son, who has read the book (which his children had not done the early ones) and loves it and in whose eyes he has become a mensch.

As an Uber worker Paul points out in the book, he has to be constantly rated, and he is only hirable if he gets five stars. A customer writes he is too untalkative and gives him one star, and his rating drops. Employers no longer fear employees. It's a tough world out there. What happened to Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité?

In the neat final scene of this neat little film, the client after the book signing thanks Paul for his toilet repair, gives him the 25 euros, and says, "My friend is moving tomorrow morning. Can I recommend you to her?" and Paul says, "Yes. But I don't work mornings. Mornings I write." End of story.

At Work/À pied d'oeuvre, 92 mins., premiered in competition at Venice Aug. 29, 2025, showing also at Hamburg, Marrakech and Göteborg, and opened Feb, 4 in France and will open Mar. 5 in Italy. AlloCiné press rating 3.9 (78%). Screened for this review as part of the Rendez-Vous with French Cinema at Lincoln Center Mar. 5-15, 2026.

Sunday, March 8 at 9:00pm – Q&A with Valérie Donzelli

Friday, March 13 at 4:00pm

Last edited by Chris Knipp; Yesterday at 01:53 AM.

-

Favorites of 2025

AUSTIN BUTLER IN THE BIKERIDERS

C H R I S__K N I P P'S__2 0 2 4__M O V I E__B E S T__L I S T S

FEATURE FILMS

All We Imagine as Light (Payal Kapadia)

Anora (Sean Baker)

Beast, The (Bertrand Bonello)

Bikeriders, THe (Jeff Nichols)

Blitz (Steve McQueen)

Challengers (Luca Guadagnino)

Close Your Eyes (Victor Erice)

Conclave (Edward Berger)

Goldman Case, The/Le Procès Goldman (Cédric Kahn)

Real Pain, A (Jesse Eisenberg)

Sing Sing (Greg Kwedar)

RUNNERS UP

The Damned (Roberto Minvervini)

BEST DOCUMENTARIES

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressberger (David Hinton)

Merchant Ivory (Stephen Soucy)

New Kind of Wilderness, A (Silje Evensmo Jacobsen)

No Other Land (Basel Adra, Rachel Szor, Hamdan Ballal, Yuval Abraham)

Sugarcane (Emily Kassie, Julian Brave NoiseCat)

UNRELEASED FAVORITES

Afternoons of Solitude/Tardes de soledad (Albert Serra)

Caught by the Tides/ 风流一代 (Jia Zhang-ke)

NOT SEEN YET

Babygirl (Halina Reijn) Dec. 25 release

Complete Unknown, A (James Mangold) Dec. 25 release

Misericordia (Alain Guiraudie) (also unreleased)

Nickel Boys (RaMell Ross) Dec. 13 release

LESS ENTHUSIASTIC ABOUT THAN SOME

Brutalist, The (Brady Corbet)

Civil War (Alex Garland)

Emilia Pérez (Jacques Audiard)

La Chimera La chimera (Alice Rohrwacher)

Megalopolis (Francis Ford Coppola)

Queer (Luca Guadagnino 2024)

Room Next Door, The (Almodóvar)

Substance, The (Coralie Fargeat)

____________________________

COMMENTS (Dec. 1, 2024)

Just a first draft; a work in progress. But I can guarantee that "Best Features" is a list only of new movies I have watched this year with a lot of pleasure and admiration and think you would enjoy. I'll be working on it. I tend to forget things, and there are late arrivals. I also may make it numerical but for now it's alphabetical. I'm expecting a lot of Babygirl, and as always there are buzz-worthy 2024 films I have not yet seen, notably Nickel Boys. I stive to focus on movies available to everyone to watch, but that's less a problem now that there are so many eventual releases on platforms. As for the "Less Enthusiastic" list, I recommend that you watch them too, because people are talking about them - a lot, especially The Brutalist, The Substance, and Emilia Pérez.

And then there's Megalopolis. Whether or not they are as great, or for that matter as awful, as some people are claiming, they will be talked about during awards season.

Enjoy - and try to get out to see all you can in a movie theter!

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 02-08-2026 at 11:13 PM.

-

CAANFEST May 2025 THREE PALESTINIAN FILMS

CAAMFEST May 8-11, 2025 Berkeley Three Muslim and Palestinian related films

PALESTINIAN LANDSCAPES

Palestinian Landscapes brings together two powerful films exploring empire, ecology, and resistance. Razan Alsalah’s A Stone’s Throw evokes dreamlike cycles of displacement and return across fragmented geographies shaped by resource and labor economies. In Foragers, Jumana Manna traces the criminalization of foraging in Palestine, revealing how colonial legal systems regulate access to land and tradition.

A Stone’s Throw, directed by Razan AlSalah

Sunday, May 11, 5:00 pm | Roxie

Amine, a Palestinian elder, is exiled twice, from land and labor, from Haifa to Beirut to a Gulf offshore oil platform. A Stone’s Throw rehearses a history of the Palestinian resistance when, in 1936, the oil labourers of Haifa blow up a BP pipeline.

Director Razan AlSalah is a Palestinian artist and teacher

*Screener available

Foragers, directed by Jumana Manna

Sunday, May 11, 5:00 pm | Roxie

Elderly Palestinians are caught between their right to forage their own land and the harsh restrictions imposed by their occupiers on the basis of preservation.

Director/Producer/Co-Editor Jumana Manna is a Palestinian visual artist

AGAINST AMNESIA: Screening & Seminar

This program, in partnership with the Berkeley-based Islamic Scholarship Fund, explores the intertwined histories and ongoing realities of displacement, colonial violence, and resistance in Palestine and Bangladesh. Through a narrative short about a Palestinian grandmother uprooted from her home and a documentary on the forgotten 1970s genocide in Bangladesh, the program highlights the the ways in which historical violence shapes mundane aspects of everyday life. A facilitated discussion will follow.

Bengal Memory, directed by Fahim Hamid

Sunday, May 11, 3:00 p.m. | AMC Kabuki 3

A Bangladeshi American explores his father’s memories of a forgotten genocide in their

native country and uncovers the controversial role the U.S. played in it.

Director/Producer/Editor Fahim Hamid was born in Bangladesh

*Screener available

Maqluba, directed by Mike Elsherif

Sunday, May 11, 3:00 p.m. | AMC Kabuki 3

Laila, a Palestinian-American drummer, visits her grandmother in her new apartment during a powerful storm under the guise of helping her unpack. But her nefarious goals slowly unfold as they delve deeper into the mystical fateful night.

Writer/Director/Producer Mike Elsherif is a Palestinian-American filmmaker

*Screener available

SHORT

Billo Rani, directed by Angbeen Saleem

Part of the Shorts Program: Centerpiece Shorts

Sunday, May 11, 12:00pm | Roxie

When Hafsa, a sparkly and impulsive 12-year-old girl, is made aware of her unibrow at Islamic Sunday School in a lesson on “cleanliness”, her eyebrows come alive and begin to speak to her.

The film is set in an Islamic Sunday School and centers around a South Asian Muslim girl

Director/Writer/Producer Angbeen Saleem is a Pakistani Muslim artist

*Screener Available

A Stone's Throw

https://vimeo.com/868181676

pw: 7aifa

Bengal Memory

https://gumlet.tv/watch/67dc1999982f3b096493d238

pw: DOC1971!

Maqluba

https://vimeo.com/998772961?ts=0&share=copy

pw: teta

Billo Rani

https://vimeo.com/1019601428?share=copy

pw: threaded

--

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 04-14-2025 at 11:04 PM.

-

THE ETERNAL DAUGHTER (Joanna Hogg 2022)

JOANNA HOGG: THE ETERNAL DAUGHTER (2022)

TILDA SWINTON IN THE ETERNAL DAUGHTER

A trip north

The Eternal Daughter may be categorized as a film of horror or the supernatural, but devotees of either will doubtless be disappointed. Numerous critics describe it as "a distinctly minor work" by the director, whose 2019 The Souvenir brought her to wide attention, and to mine. It's worth going back and watching all her three earlier features, Unrelated, Archipelago and Exhibition: they're not fun watches, but the unfun-ness is distinctly her own, uppermiddleclass British constraints and torments that will seem to grow out of, not lead into, the autobiographical film student with the unfortunate posh boyfriend of The Souvenir. The underimpressed critics also say The Eternal Daughter, which serves as a sequel to The Souvenir II, the end of a trilogy, that it is "slooow."

Well, The Eternal Daughter is unique, and while I'd agree it has its longeurs, and is almost Beckettian in its uneventfulness. It's also subtle and beautiful, and the performance at the center of it by Tilda Swinton as both Julie Hart, a filmmaker, and Rosalind Hart, her mother, whom the hyper-attentive Julie takes to a big old, apparently empty hotel for her birthday, is remarkable. The double performance is not just a stunt. It's also a brilliant idea central to the film's themes and ideas, which magnify and unfold over time like the old Japanese paper flowers that grew when you dipped them in water. And all this isn't just cleverness. It serves to deliver hard emotional honesty that characterizes Hogg's best moments in the other films. After the slow passages, as I watched, the emotion grew, and at the end I was devastated with a still unfolding sense of sorrow too deep for tears.

Hogg makes much use of the horror vibe and genre ticks throughout - a pale face in a window; knocks in the night; Rosalind's setter Louis (the canine companion an important character in many a family), brought along, disappearing and then popping up back in the room; the odd, unfriendly "staff;" the confounding corridors and rooms; the fog outside - and all these events and things allow for the general feeling we have that something strange is going on. Many will doubtless guess the film's secret early on. That's unimportant. It's all in the very distinctive nuance of the film and the interchanges between Julie and Rosalind. It's very important that until the end, a two-shot doesn't occur. You see Julie saying something, then you see - or will you see? You never know - Rosalind. And yes, you're very aware that both are Tilda Swinton in two different sorts of drag. The Rosalind drag includes peculiarly subtle aging makeup. She's not made to look very old. (A very old woman is seen toward the end, in a kind of coda and subtly spooky jolt.) You're marveling at the costumer's and makeup artist's art and the acting, but you're very aware that you're watching Tilda Swinton.

And all this is kind of creepy, if not what you'd call "horrible." Or maybe it is; maybe you can anticipate a Hitchcockian shock coming. It's not like that. It's more like the air goes out of the tire. (Or tyre.) The more overt horror-supernatural vibe comes from the great aristocratic house in Wales that Julie and Rosalind are staying at. It is a place, then in private hands, where Rosalind, as a young girl, was sent with other family members to escape the bombing during the War. But Julie doesn't know much about this. She has devoted much of her life to caring about and loving her mother - she has a husband, but no children - but her mother remains largely a mystery to her. Other later visits to the house turn out to have occurred later, and things happened, not happy memories, that Julie didn't know about. The place is beautiful, in a mournful way. The accoutrements of the rooms, even the keys at the front desk, are handsome. the ornate, formal landscaping outside, shrouded often in cinematic fog, is beautiful in its layers of green. The exterior shots look like subtle color lithographs.

The place isn't particularly friendly. Julie and Rosalind are greeted by a grumpy receptionist (Carly-Sophia Davies), who also reappears as the waitress at the dining room (and there are only four dishes on the menu). Is Harold Pinter an influence? This is in some ways like a magnificently visually expanded play, a chamber drama, a drama in the head. A warmer character is a groundskeeper (Joseph Mydell) who talks to Julie a few times and comforts and shares an understanding of loss. He says his wife died a year ago.

Julie is here to celebrate Rosalind's birthday - or is she? The birthday celebration turns out to be grotesque and sad, family happiness gone wrong, though a a bottle of champagne is uncorked and poured from and a birthday cake is brought in. Julie chooses to bring it in herself. But whenever Julie and Rosalind are seated talking together at meals, Julie surreptitiously sets her smartphone out to record the conversation. Early on she's said she's here to work, on a new film presumably, and she goes to a special place to do so, but she can't sleep, she's uncomfortable, and she goes day after day without getting any work done. The other use of the smartphone is to try to talk to her husband. This she has to do out in front of the hotel pacing about near a hedge trying to get reception, which isn't good. And the wi-fi is patchy in the building as well.

These descriptions sound ordinary enough. But in Joanna Hogg's skilled hands and the meticulous, complicated interchanges of Tilda and Tilda, they resonate with meanings you go on pondering long after the film is over. The heart of the matter is the confrontation of lives and family relationships, the permanent, difficult, mysterious, inescapable ones. The daughter is "eternal" because filial relationships never end. Imagine making a movie about your mother and its turning out to be a sort of horror film. Others would make a story that's joyous and celebratory. But where is the truth? I remember the priest who Malraux talks about in his Anti-Memoirs who, questioned on what he had learned about people from thirty years of hearing confession, gave two ideas; there is no such thing as a grownup person; and people are much less happy than they appear. But the scenes we have watched have been an expiation. And the end Julie has come thorough and is typing away on her laptop: the new film has come to her. This one.

If any of this sounds intriguing, you are urged to see The Eternal Daughter. It's a marvelous film, a study of grief, memory and family relationships that cuts to the bone. A minor work? Remember the little Fragonard painting in the Wallace Collection in The Souvenir. That whole film grows out of it.

The Eternal Daughter, 96 mins., debuted Sept. 6, 2022 at Venice, showing at nine or more other international festivals, including Toronto, Zurich, London, New York (Main Slate), Vienna, Seville, AFI, Thessaloniki and Marrakech. Limited US theatrical release and on itnernet Dec. 2, 2022. Metacritic rating: 79%.

Last edited by Chris Knipp; 12-06-2022 at 08:01 PM.

Posting Permissions

Posting Permissions

- You may not post new threads

- You may not post replies

- You may not post attachments

- You may not edit your posts

-

Forum Rules

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks